If the birth lottery wasn’t already clear enough, here’s a synthesis of research studies, data, and examples.

“Some people defy every expectation, achieving remarkable things in the face of adversity. It is tempting to view such lives as evidence that we can, after all, be the masters of our own destiny, but to do so would be a mistake. Forces beyond our control determine the resources – psychological, physical and material – at our disposal to carve out a new path, and these resources, along with countless other twists of fate, ultimately determine how successful we will be in our attempt. For every unlikely success story there are countless people of equal potential who died in poverty and obscurity due to the crushing force of circumstance. Just because the odd person wins the lottery does not mean the game isn’t rigged for everyone else to lose.” — Raoul Martinez

🔒 Premium members also have access to the companion posts:

· Lottery of Birth Synthesis: How to See Yourself and the World Drastically Differently (+ Infographic)

· Behind the Scenes: Dissecting my own Lottery of Birth Ticket

Quick Housekeeping:

- All content in “quotation marks” is directly from the original authors.

- All content is organized into my own themes.

- Emphasis has been added in bold for readability/skimmability.

Post Contents:

25+ Birth Lottery Implications to Clearly See why it Matters so Much

Life & Death

- “A baby born in Japan is 50 times more likely to reach its first birthday than a baby born in Angola.” — Raoul Martinez

- “An African-American infant is twice as likely to pass away in its first year as a white American child.” — Raoul Martinez

- “From 1990 to 2015, the number of children who died before their fifth birthday – mostly from preventable diseases – is roughly 236 million. And if we make it into adulthood free from abuse, violence, neglect, war, famine, malnutrition, physical or mental illness, extreme poverty, debilitating injury, or the loss of a parent or sibling, we are luckier than most.” — Raoul Martinez

Nurture & Development

Relationship with parent(s)/primary caregiver(s):

- “In the 1950s, British psychiatrist John Bowlby showed that a child’s relationship with its primary care-giver has a decisive impact on emotional and mental development. Today, it is widely accepted among child psychologists that if a child fails to form a secure attachment to a care-giver, the likelihood increases of developing a range of behavioural problems related to depleted self-worth, lack of trust in other people and an absence of empathy.” — Raoul Martinez

- “We do not hold someone with schizophrenia responsible for having a hallucination, just as we don’t hold someone with diabetes responsible for their increased thirst. In the case of the person with diabetes, we ‘blame’ the person’s low levels of insulin, or the person’s cells for not responding normally to insulin. That is, we recognize the biomedical causes of the behaviour. Equally, if someone’s behaviour is the result of their low empathy, which itself stems from the underactivity of the brain’s empathy circuit, and which ultimately is the result of their genetic make-up and/or their early experience, in what sense is the ‘person’ responsible?” — Simon Baron-Cohen, Professor of Developmental Psychopathology and a leading researcher in empathetic development

Socialization & social deprivation:

- “Every individual is born into an objective social structure within which he encounters the significant others who are in charge of his socialization. These significant others are imposed upon him. Their definitions of his situation are posited for him as objective reality. He is thus born into not only an objective social structure but also an objective social world. The significant others who mediate this world to him modify it in the course of mediating it. They select aspects of it in accordance with their own location in the social structure, and also by virtue of their individual, biographically rooted idiosyncrasies. The social world is ‘filtered’ to the individual through this double selectivity.” — Peter Berger & Thomas Luckmann

- “The lower-class child not only absorbs a lower-class perspective on the social world, he absorbs it in the idiosyncratic coloration given it by his parents (or whatever other individuals are in charge of his primary socialization). The same lower-class perspective may induce a mood of contentment, resignation, bitter resentment, or seething rebelliousness. Consequently, the lower-class child will not only come to inhabit a world greatly different from that of an upper-class child, but may do so in a manner quite different from the lower-class child next door.” — Peter Berger & Thomas Luckmann

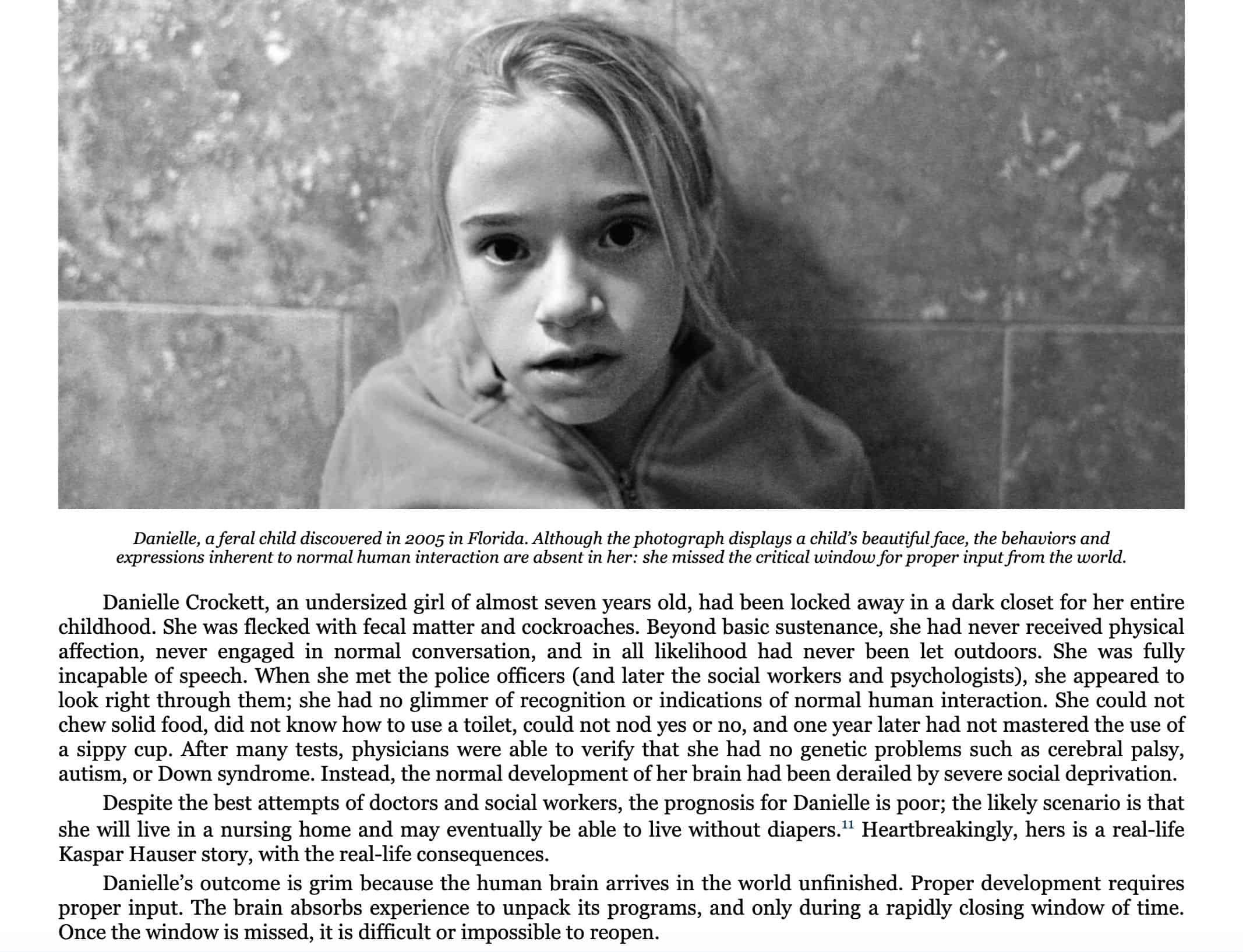

- “Brains are most flexible at the beginning, in a window of time known as the sensitive period. As this period passes, the neural geography becomes more difficult to change … The ability to learn language, possess vision, interact socially, walk normally, and have normal neurodevelopment is limited to the years of young childhood. After a certain point, these abilities are lost. The brain needs to experience the proper input within the right window to achieve its most useful connectivity.” — David Eagleman

- “The normal development of the brain can be derailed by severe social deprivation … A child raised without human interaction does not grow up to walk, speak, write, lecture, and thrive.” — David Eagleman

Word gap & gesture gap:

- “Decades of research have revealed the impact of early experiences on the development of our innate capacities. For instance, children from lower-income families with less-educated parents enter school far behind their wealthier counterparts in language skills. The amount of time our care-givers spend conversing, reading and playing with us – and the quality of those interactions – all makes a difference to our development. Stanford psychologists have shown that two-year-old children from poor families may already be six months behind in language development. By age four, children in middle- and upper-class families hear in the region of 30 million more words than children from families on welfare.” — Raoul Martinez

- “A study conducted by the Scottish Centre for Social Research (SCSR), which tracked the abilities of 14,000 youngsters, found that by age five, children with degree-level educated parents are, on average, a year and a half ahead of their less privileged counterparts in terms of vocabulary and around thirteen months ahead on problem-solving.” — Raoul Martinez

- “Child development experts have long emphasized the importance of talking to children; an often cited 1995 study carried out by psychologists Betty Hart and Todd Risley estimated a 30-million ‘word gap’ in the number of words heard spoken aloud by affluent and poor children by the time they start school. Since the publication of the Hart-Risley study, other research has confirmed that higher-income parents tend to talk more than lower-income parents, that they employ a greater diversity of word types, that they compose more complex and more varied sentences—and that these differences are predictive of child vocabulary.” — The Extended Mind

- “Now researchers are generating evidence that how parents gesture with their children matters as well—and that socieconomic differences in how often parents use their hands when talking to children may be producing what we could call a ‘gesture gap.’ High-income parents gesture more than low-income parents, research finds. And it’s not just the quantity of gesture that differs but also the quality: more affluent parents provide a greater variety of types of gesture, representing more categories of meaning—physical objects, abstract concepts, social signals. Parents and children from poorer backgrounds, meanwhile, tend to use a narrower range of gestures when they interact with each other. Following the example set by their parents, high-income kids gesture more than their low-income counterparts. In one study, fourteen-month-old children from high-income, well-educated families used gesture to convey an average of twenty-four different meanings during a ninety-minute observation session, while children from lower-income families conveyed only thirteen meanings. Four years later, when it was time to start school, children from the richer families scored an average of 117 on a measure of vocabulary comprehension, compared to 93 for children from the poorer families.” — The Extended Mind

Decentration & decontextualization:

- “Several cultural dimensions in the use of language have been found to correlate with the ability to achieve ‘decentration’ (In Piagetian theory, decentering refers to the process by which an egocentric cognitive position is replaced by a more ‘objective’ one in order to reconcile disjunctions between conceptual schemes and empirical experience). Lower-class children were found far less able to achieve decentration than middle-class children (Bruner, 1973).” — Jack Mezirow

- “Middle-class children more commonly tend to use language as an instrument of analysis and synthesis in abstract problem solving and for ‘decontextualization.’ This important term refers to using language without dependence upon shared perceptions or action, permitting one to conceive of information as independent of the speaker’s point of view and to communicate with those outside one’s daily experience regardless of their affiliation or location. In observing these class-related differences in language usage among children, Bruner comments, ‘I do not know, save by everyday observation, whether the difference is greater still among adults, but my impression is that the difference in decontextualization is greater between an English barrister and a dock worker than it is between their children’.” — Jack Mezirow

- “A necessary inference from Bruner’s findings is that, if indeed some adult cultures discourage development of the self-awareness essential for decentration, decontextualization, and a sense of identity in their children, these same deprivations and their consequent constraints must, ipso facto, pertain in adulthood. Moreover, there is reason to believe that this condition pertains not only to most people in some places but to some people in most places.” — Jack Mezirow

Trauma & Addiction

Childhood traumas:

- “Stressful or traumatic childhood experiences such as abuse, neglect, witnessing domestic violence, or growing up with alcohol or other substance abuse, mental illness, parental discord, or crime in the home…are a common pathway to social, emotional, and cognitive impairments that lead to increased risk…of violence or re-victimization, disease, disability and premature mortality.” — Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study

- “The prevalence of and risks associated with these problems are greater in people who have experienced more abuse. For instance, each traumatic event in a child’s life makes them two to four times more likely to develop an addiction.” — Raoul Martinez

Addictions:

- “Dr Gabor Maté, a physician specialising in the treatment of addiction, argues that physical and emotional interactions determine much of our neurological growth and that addiction is largely a product of life-experience, particularly in early childhood.” — Raoul Martinez

- “Endorphins are released in the infant’s brain when there are warm, non-stressed, calm interactions with the parenting figures. Endorphins, in turn, promote the growth of receptors and nerve cells, and the discharge of other important brain chemicals. The fewer endorphin-enhancing experiences in infancy and early childhood, the greater the need for external sources. Hence, a greater vulnerability to addictions.” — Gabor Maté

Food & Obesity

Food choices:

- “Our food choices have been restricted and shaped before we ever really think about them. Consumption habits, like all habits, are shaped by forces ‘beyond our control’. In the case of food, they are formed at an early age and are lifelong – the $10 billion spent annually on marketing food to children in the US is clearly a long-term investment. The ideas, values and images we encounter in our environment shape our dietary habits.” — Raoul Martinez

- “A striking example is Fiji, where, in 1990, eating disorders were unheard of. In 1995, television was introduced, mostly from the US and packed with advertising. Within three years, 12% of teenage girls in Fiji had developed bulimia.” — Raoul Martinez

Obesity:

- “Take, for instance, the growing problem of obesity. In a 2005 study, Abigail Saguy and Rene Almeling looked at 221 newspaper, medical and book sources and found that, while two-thirds cited individual causes of obesity, less than a third gave any mention to structural factors such as geography, longer working hours, the fast food industry or reduced income. Revealingly, the tendency of the sources to focus on personal responsibility increased when discussing particular social groups: 73% of articles mentioning the poor or people of colour blamed obesity on bad food choices, whereas in articles that did not mention these groups, the figure dropped to only 29%.” — Raoul Martinez

- “Raj Patel, in his book on the food industry, Stuffed and Starved (2007), shows that this approach ignores important realities. Poor neighbourhoods, while boasting a higher concentration of fast food restaurants, have on average four times fewer supermarkets than affluent areas. In other words, people of colour and the poor live in environments that are far more likely to result in obesity. By contrast, richer, whiter areas are more likely to provide access to healthier, fresh, nutritious food, lower in salt and fat.” — Raoul Martinez

- “Many choices have already been made for us by our environment, our customs, our routine. Choice is the word we’re left with to describe our plucking one box rather than another off the shelves, and it’s the word we’re taught to use. If we’re asked why we use the word ‘choice’ to describe this, we might respond ‘no one pointed a gun to our head, no one coerced us’ as if this were the opposite to choice. But the opposite of choice isn’t coercion. It’s instinct. And our instincts have been so thoroughly captured by forces beyond our control that they’re suspect to the core.” — Raj Patel

Money & Mobility

Inheritance & parents’ jobs/income:

- “Today, the descendants of the nineteenth century’s upper classes are not only richer, but more likely to live longer, attend Oxford or Cambridge and end up a doctor or lawyer. And there is no sign of any let-up in the power of inheritance to shape the world. The wealth transferred via inheritance from one generation to the next is set to break all records.” — Raoul Martinez

- “The notion of the American Dream—that, unlike old Europe, we are a land of opportunity—is part of our essence. Yet the numbers say otherwise. The life prospects of a young American depend more on the income and education of his or her parents than in almost any other advanced country. When poor-boy-makes-good anecdotes get passed around in the media, that is precisely because such stories are so rare.” — Joseph Stiglitz, recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences

- “A lot of Americans think the U.S. has more social mobility than other western industrialized countries. (It’s) abundantly clear that we have less … Your circumstances at birth—specifically, what your parents do for a living—are an even bigger factor in how far you get in life than we had previously realized. Generations of Americans considered the United States to be a land of opportunity. This research raises some sobering questions about that image.” — Michael Hout, Professor of Sociology at New York University

- “In the US, only 9% of students in elite universities come from the poorer half of the population. Another study released in 2015 by the UK Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission exploded the myth of a meritocratic society. According to its findings, children from wealthier families with less academic intelligence than their poorer counterparts were nevertheless 35% more likely to end up becoming high earners. Wealthy parents employ a range of strategies to ensure their children end up in ‘top jobs’ but, whether it’s by tapping into powerful personal networks or subsidising unpaid internships, the result is the same: an absence of downward mobility. And, because high-earning jobs are in limited supply, gifted students from less advantaged backgrounds face an uphill struggle to turn their potential into market rewards.” — Raoul Martinez

Money desires:

- “All of us go through life anchored to a set of views about how money works that vary wildly from person to person … People’s lifetime investment decisions are heavily anchored to the experiences they had in their own generation—especially experiences early in their adult life … The economists wrote: ‘Our findings suggest that individual investors’ willingness to bear risk depends on personal history.’ Not intelligence, or education, or sophistication. Just the dumb luck of when and where you were born.” — Morgan Housel

- “The importance that people attached to income at age 18 also anticipated their satisfaction with their income as adults.” — Daniel Kahneman

Gender & income/salary:

- “Another factor that influences income is gender. For all the gains feminism has made, men still earn more than women in almost all nations. This disparity exists for a variety of reasons that are not easy to untangle – unequal caring responsibilities, undervaluing work traditionally done by women – but discrimination remains a factor.” — Raoul Martinez

- “We are highly influenced by the events in our childhoods. As an interesting example, consider the correlation between how tall a man is and how much salary he will command. In America, each additional inch of height translates into a 1.8% increase in take-home pay. Why is this? The popular assumption is that this stems from discrimination in hiring practices: everyone wants to hire the tall guy because of his commanding presence. But it turns out there’s a deeper reason. The best indicator of a male’s future salary is how tall he was at the age of sixteen. However tall he grows after that doesn’t change the outcome. How do we understand this? Could it be some effect of nutritional differences between people? No: when the researchers correlated with height at ages seven and eleven, the effect was not as strong. Instead, the teenage years are a time when social status is being worked out, and as a result who you are as an adult strongly depends on who you were then. In fact, studies that track thousands of children into adulthood find that socially oriented careers, such as sales or managing other people, show the strongest effect of teenage height. Other careers, such as blue-collar work or artistic trades, are less influenced. How people treat you during your formative years has a great deal of impact on your comportment in the world, in terms of self-esteem, confidence, and leadership.” — David Eagleman

Crime & Punishment

Childhood misbehavior:

- “The logic of deterrence fails and, once expelled, the likelihood of a child ending up in juvenile detention greatly increases. American clinical child psychologist Dr Ross Greene has pioneered an approach now known as Collaborative & Proactive Solutions (CPS). It starts with the assumption that kids want to do well. If they’re not doing well, it’s because they lack the necessary skills. Disruptive children are not simply attention-seeking, manipulative or poorly motivated, they are struggling to meet the demands being made of them. CPS takes seriously the fact that the rules and expectations of the classroom and schoolyard do not bear equally on all. For instance, children with learning disabilities and diagnosed behaviour problems are twice as likely to be suspended and three times more likely to be imprisoned than their peers.” — Raoul Martinez

Inequality & violence:

- “The most established environmental determinant of violence in a society is income inequality. Less equal societies are more violent. The link between inequality and homicide rates, within and between countries, has been revealed in dozens of independent studies – and the differences are not small. According to the Equality Trust in the UK, there are five-fold differences in murder rates related to inequality between different nations. In fact, higher rates of inequality are associated with a host of social problems: mental illness, child bullying, drug use, teenage pregnancy, divorce, illiteracy and distrust.” — Raoul Martinez

- “In societies where income differences between rich and poor are smaller, the statistics show that community life is stronger and levels of trust are higher. There is also less violence, including lower homicide rates; physical and mental health tends to be better and life expectancy is higher. In fact, most of the problems related to relative deprivation are reduced: prison populations are smaller, teenage birth rates are lower, educational scores tend to be higher, there is less obesity and more social mobility. What is surprising is how big these differences are. Mental illness is three times more common in more unequal countries than in the most equal, obesity rates are twice as high, rates of imprisonment eight times higher, and teenage births increase tenfold.” — Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson

Prison:

- “Having spent over thirty years at the UK criminal bar, and ‘rather a lot of time in prisons’, Baroness Helena Kennedy QC speaks from experience when she writes: ‘For most people, prison is the end of a road paved with deprivation, disadvantage, abuse, discrimination and multiple social problems. Empty lives produce crime…The same issues arise repeatedly: appalling family circumstances, histories of neglect, abuse and sexual exploitation, poor health, mental disorders, lack of support, inadequate housing or homelessness, poverty and debt, and little expectation of change…It is my idea of hell.'” — Raoul Martinez

- “In our society, children subjected to the harshest, most impoverished environments are increasingly being criminalised. Kennedy remarks that ‘90% of young people in prison have mental health or substance abuse problems. Nearly a quarter have literacy and numeracy skills below those of an average seven-year-old and a significant number have suffered physical and sexual abuse.'” — Raoul Martinez

- “Ultimately, all that separates the criminal and non-criminal is luck. The skewed distribution of ‘racial luck’ is particularly disturbing. Although black people make up only 12% of the US population, they account for 40% of its prison population. Across the US today, black people are more than six times as likely to be imprisoned than whites, 31% more likely to be pulled over while driving than white drivers, and twice as likely to be killed by a cop (and more likely to be unarmed when killed). Racial prejudice permeates almost every area of American society, greatly diminishing the opportunities available to black people and ethnic minorities.” — Raoul Martinez

You May Also Enjoy: