The parable of the blind men and the elephant dates back to Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain writings.

Apparently, the Buddhist text Udana 6.4 contains one of the earliest versions of the story—dated all the way back to around c. 500 BCE. (1)

The Blind Men and The Elephant: A Short Story about Perspective

While there have been a variety of versions over the centuries, one poem in particular seems to be responsible for popularizing it in modern times.

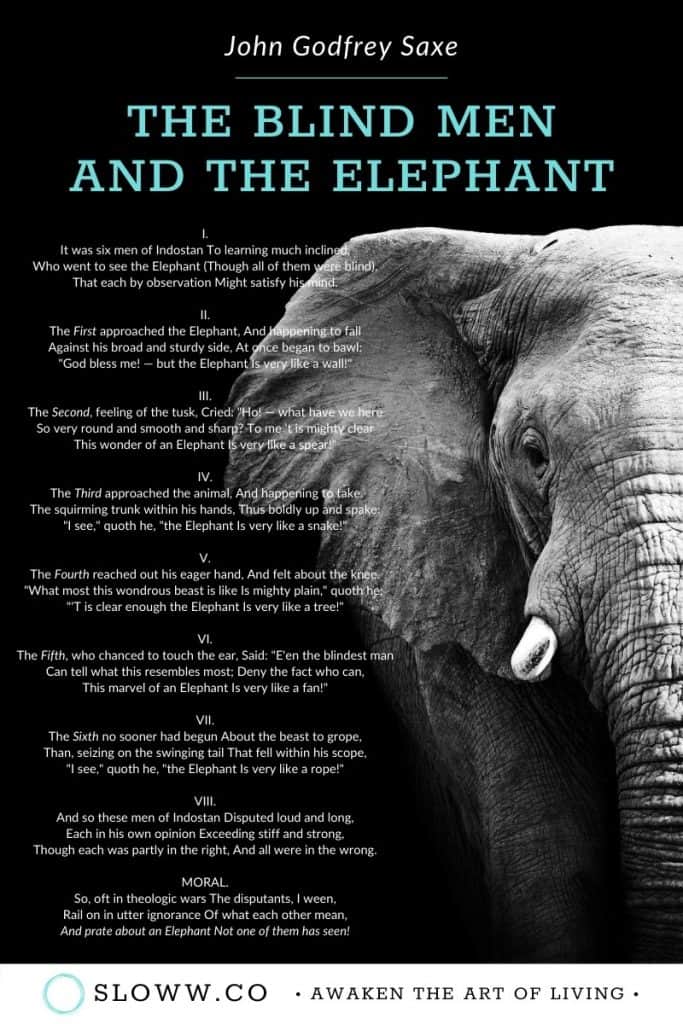

John Godfrey Saxe Version

American poet John Godfrey Saxe wrote his version of “The Blind Men and the Elephant” in the mid-nineteenth century.

I’ve included this version below in video, image, and text forms so you can listen and/or read. Enjoy!

I.

It was six men of Indostan

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind.

II.

The First approached the Elephant,

And happening to fall

Against his broad and sturdy side,

At once began to bawl:

“God bless me! — but the Elephant

Is very like a wall!”

III.

The Second, feeling of the tusk,

Cried: “Ho! — what have we here

So very round and smooth and sharp?

To me ‘t is mighty clear

This wonder of an Elephant

Is very like a spear!”

IV.

The Third approached the animal,

And happening to take

The squirming trunk within his hands,

Thus boldly up and spake:

“I see,” quoth he, “the Elephant

Is very like a snake!”

V.

The Fourth reached out his eager hand,

And felt about the knee.

“What most this wondrous beast is like

Is mighty plain,” quoth he;

“‘T is clear enough the Elephant

Is very like a tree!”

VI.

The Fifth, who chanced to touch the ear,

Said: “E’en the blindest man

Can tell what this resembles most;

Deny the fact who can,

This marvel of an Elephant

Is very like a fan!”

VII.

The Sixth no sooner had begun

About the beast to grope,

Than, seizing on the swinging tail

That fell within his scope,

“I see,” quoth he, “the Elephant

Is very like a rope!”

VIII.

And so these men of Indostan

Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

And all were in the wrong.

MORAL.

So, oft in theologic wars

The disputants, I ween,

Rail on in utter ignorance

Of what each other mean,

And prate about an Elephant

Not one of them has seen!

The Moral(s) of The Blind Men and The Elephant

There are quite a few lessons learned from the story of the blind men and the elephant.

1. We all have limited experience (which means partial perspective).

“Though each was partly in the right, And all were in the wrong.”

Each man believes that his individual perspective is the whole truth—when it’s actually only partial truth (and even referring to it as “truth” is a stretch as you’ll see in #4 below).

Even if two people have the same experience, the subjective interpretations of that single experience will most likely be different. For instance, two of the men could have touched the exact same part of the elephant and thought it was something different.

“The world is nothing but change. Our life is only perception.” — Marcus Aurelius, Meditations (Summary | Top Quotes)

2. If we don’t remember these limitations, we can get into trouble with ourselves and others.

“Disputed loud and long, Each in his own opinion”

With ourselves, we can become deluded—thinking we’ve figured everything out and understand the whole of something.

If we take this approach with others—who may feel the exact same way—it can lead to conflict that often escalates.

“I have one major rule: Everybody is right. More specifically, everybody — including me — has some important pieces of truth, and all of those pieces need to be honored, cherished, and included in a more gracious, spacious, and compassionate embrace.” — Ken Wilber

3. The “elephant” represents many different things in life that we can’t see.

“And prate about an Elephant Not one of them has seen!”

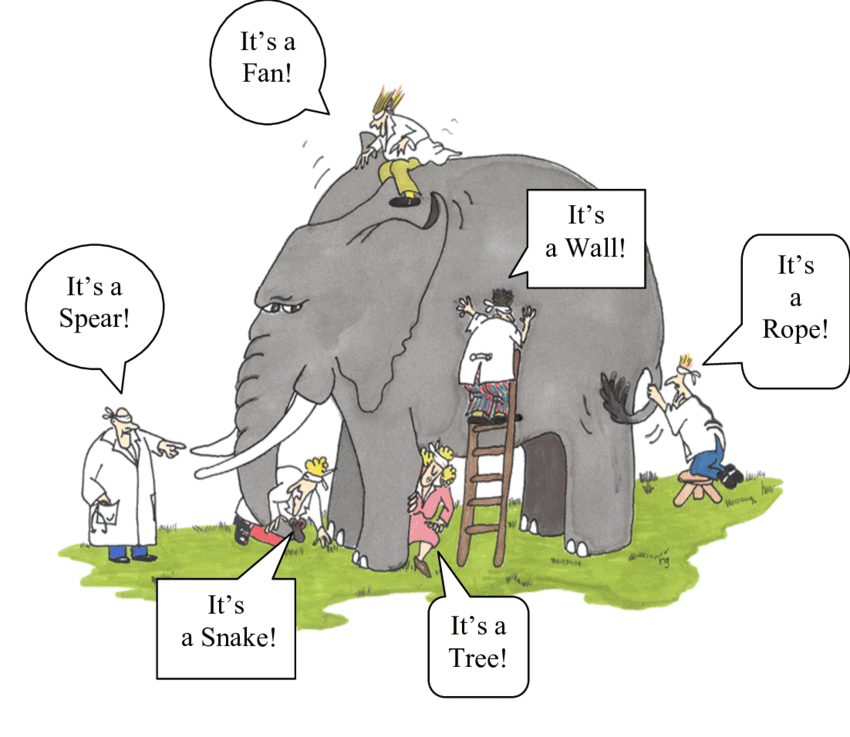

With the poem, we are an outside observer of the ridiculous situation unfolding with the blind men. We can see the elephant that they can’t see.

But, in real life, we are the blind men and can’t see these “elephants.” They can be anything: truth, reality, spirit, etc. Ultimately, we have no idea what ultimate truth is.

“The most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about.” — David Foster Wallace, This is Water (Summary)

4. Our senses offer limited information (and even this isn’t reality itself).

Let’s go to an even deeper level.

Our brain is literally blind—it lives in a vault of silence and darkness inside your skull:

“Consider that whole beautiful world around you, with all its colors and sounds and smells and textures. Your brain is not directly experiencing any of that. Instead, your brain is locked in a vault of silence and darkness inside your skull. All it ever experiences are electrochemical signals coursing around through its massive jungle of neurons. Those signals are all it has to work with and nothing more. From these signals it extracts patterns, assigns meaning to them, and creates your subjective experience of the outside world. Your reality is running entirely in a dark theater. Our conscious experience of the outside world is one of the great mysteries of neuroscience: not only do we not have a theory to explain how private subjective experience emerges from a network of cells, we currently aren’t even certain what such a theory would look like.” — David Eagleman, Neuroscientist (2)

5. Embrace the diversity of the individual as part of the unity of the collective.

It seems that ultimate reality may allow for all realities.

“Therefore it would seem that the ideal or ultimate aim of Nature must be to develop the individual and all individuals to their full capacity, to develop the community and all communities to the full expression of that many-sided existence and potentiality which their differences were created to express, and to evolve the united life of mankind to its full common capacity and satisfaction, not by suppression of the fullness of life of the individual or the smaller commonality, but by full advantage taken of the diversity which they develop.” — Sri Aurobindo

Bonus:

Here’s another take on it from the book Introduction to Interdisciplinary Studies:

“A sophisticated epistemic position understands that research conducted by the disciplines is similar to the activity of the blind men trying to make sense of the elephant. We can compare these men to disciplinary experts who are trying to understand a complex phenomenon (i.e., the elephant). They naturally concentrate on that part of the phenomenon that their disciplinary training has taught them to focus on: One disciplinary expert concentrates on the trunk, another focuses on the tusks, and others study the ears, body, legs, or tail. Their disciplinary training has equipped them to approach the problem with a specialized toolkit of assumptions, epistemology, concepts, theories, and methods. The disciplines are doing exactly what they are supposed to be doing: probing deeply into those parts of the problem (and only those parts) that they are uniquely designed to study and producing narrow, specialized understandings of it. Instead of dismissing conflicting insights as ‘mere opinion’ or ‘right’ or ‘wrong,’ it is best to view their work as partial or incomplete. It is left to the interdisciplinarian to look at the ‘big picture’ and research the whole elephant. We do this, not by duplicating the narrow and specialized work of the disciplinary specialists, but by critically examining their multiple and conflicting insights, integrating them, and producing a more comprehensive understanding which will lead to a workable solution. This, in a nutshell, describes interdisciplinary process. Engaging in it is possible only by exercising ‘reasoned judgment.'”

You May Also Enjoy:

- Browse all simple & short stories

Sources & Footnotes:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blind_men_and_an_elephant

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/exploring-the-mysteries-of-the-brain/