This is a book summary of Determined: A Science of Life without Free Will by Robert Sapolsky (Amazon).

Here’s a podcast intro to Robert Sapolsky and the book Determined:

Quick Housekeeping:

- All content in “quotation marks” is from the author (otherwise it’s paraphrased).

- All content is organized into my own themes (not the author’s chapters).

- Emphasis has been added in bold for readability/skimmability.

Book Summary Contents:

- About the Book

- Determinism, Chaoticism, Emergence, & Quantum

- Biology of Behavior

- One Seamless Thing

- Free Will & Intent

- Bad Luck & Good Luck

- Implications, Morals, & Justice

- Subtraction & Change

A Science of Life without Free Will: Determined by Robert Sapolsky (Book Summary)

About the book Determined

“This book has a goal—to get people to think differently about moral responsibility, blame and praise, and the notion of our being free agents. And to feel differently about those issues as well. And most of all, to change fundamental aspects of how we behave … My goal isn’t to convince you that there’s no free will; it will suffice if you merely conclude that there’s so much less free will than you thought that you have to change your thinking about some truly important things.”

- “The approach of this book is to show how determinism works, to explore how the biology over which you had no control, interacting with environment over which you had no control, made you you. And when people claim that there are causeless causes of your behavior that they call ‘free will,’ they have (a) failed to recognize or not learned about the determinism lurking beneath the surface and/or (b) erroneously concluded that the rarefied aspects of the universe that do work indeterministically can explain your character, morals, and behavior.”

- “The easy takeaway from the first half of this book is that the biological determinants of our behavior stretch widely over space and time—responding to events in front of you this instant but also to events on the other side of the planet or that shaped your ancestors centuries back. And those influences are deep and subterranean, and our ignorance of the shaping forces beneath the surface leads us to fill in the vacuum with stories of agency. Just to restate that irritatingly-familiar-by-now notion, we are nothing more or less than the sum of that which we could not control—our biology, our environments, their interactions. The most important message was that these are not all separate -ology fields producing behavior. They all merge into one—evolution produces genes marked by the epigenetics of early environment, which produce proteins that, facilitated by hormones in a particular context, work in the brain to produce you. A seamless continuum leaving no cracks between the disciplines into which to slip some free will.”

- “The theme of the second half of this book is this: We’ve done it before. Over and over, in various domains, we’ve shown that we can subtract out a belief that actions are freely, willfully chosen, as we’ve become more knowledgeable, more reflective, more modern. And the roof has not caved in; society can function without our believing that people with epilepsy are in cahoots with Satan and that mothers of people with schizophrenia caused the disease by hating their child.”

- “What the science in this book ultimately teaches is that there is no meaning. There’s no answer to ‘Why?’ beyond ‘This happened because of what came just before, which happened because of what came just before that.’ There is nothing but an empty, indifferent universe in which, occasionally, atoms come together temporarily to form things we each call Me.”

Determinism, Chaoticism, Emergence, & Quantum

“Every step in the progression of a chaotic system is made of determinism, not whim. And yes, take a huge number of simple component parts that interact in simple ways, let them interact, and stunningly adaptive complexity emerges. But the component parts remain precisely as simple, and they can’t transcend their biological constraints to contain magical things like free will.”

Determinism:

“When people claim that there are causeless causes of your behavior that they call ‘free will,’ they have (a) failed to recognize or not learned about the determinism lurking beneath the surface and/or (b) erroneously concluded that the rarefied aspects of the universe that do work indeterministically can explain your character, morals, and behavior.”

- “Every aspect of behavior has deterministic, prior causes … It’s antecedent causes all the way down, not a floating turtle or causeless cause to be found.”

- “When you behave in a particular way, which is to say when your brain has generated a particular behavior, it is because of the determinism that came just before, which was caused by the determinism just before that, and before that, all the way down.”

- “There’s no answer to ‘Why?’ beyond ‘This happened because of what came just before, which happened because of what came just before that.'”

Chaos Theory:

“Unpredictable is not the same thing as undetermined; reductive determinism is not the only kind of determinism; chaotic systems are purely deterministic, shutting down that particular angle of proclaiming the existence of free will.”

- “Determinism allows you to explain why something happened, whereas predictability allows you to say what happens next.”

- “The critical mistake running through all of this: determinism and predictability are very different things. Even if chaoticism is unpredictable, it is still deterministic … A system being unpredictable doesn’t mean that it is enchanted, and magical explanations for things aren’t really explanations.”

- “Will we ever get to the point where our behavior is entirely predictable, given the deterministic gears grinding underneath? Never—that’s one of the points of chaoticism.”

Emergent Complexity:

“Emergent complexity, while being immeasurably cool, is nonetheless not where free will exists, for three reasons: Because of the lessons of chaoticism—you can’t just follow convention and say that two things are the same, when they are different, and in a way that matters, regardless of how seemingly minuscule that difference; unpredictable doesn’t mean undetermined. Even if a system is emergent, that doesn’t mean it can choose to do whatever it wants; it is still made up of and constrained by its constituent parts, with all their mortal limits and foibles. Emergent systems can’t make the bricks that built them stop being brick-ish. These properties are all intrinsic to a deterministic world, whether chaotic, emergent, predictable, or unpredictable.”

- “Simple rules about how components of a system interact locally, repeated a huge number of times with huge numbers of those components, and out emerges optimized complexity. All without centralized authorities comparing the options and making freely chosen decisions … No matter how emergently cool, ant colonies are still made of ants that are constrained by whatever individual ants can or can’t do, and brains are still made of brain cells that function like brain cells … No matter how unpredicted an emergent property in the brain might be, neurons are not freed of their histories once they join the complexity.”

- “The whole point of emergence, the basis of its amazingness, is that those idiotically simple little building blocks that only know a few rules about interacting with their immediate neighbors remain precisely as idiotically simple when their building-block collective is outperforming urban planners with business cards. Downward causation doesn’t cause individual building blocks to acquire complicated skills; instead, it determines the contexts in which the blocks are doing their idiotically simple things. Individual neurons don’t become causeless causes that defy gravity and help generate free will just because they’re interacting with lots of other neurons.”

- “Philosophers discuss ‘weak emergence,’ which is where no matter how cool, ornate, unexpected, and adaptive an emergent state is, it is still constrained by what its reductive bricks can and can’t do. This is contrasted with ‘strong emergence,’ where the emergent state that emerges from the micro can no longer be deduced from it, even in chaoticism’s sense of a stepwise manner.”

Quantum Indeterminacy:

“Even if quantum effects bubbled up enough to make our macro world as indeterministic as our micro one is, this would not be a mechanism for free will worth wanting. That is, unless you figure out a way where we can supposedly harness the randomness of quantum indeterminacy to direct the consistencies of who we are … If you base your notion of being a free, willful agent on randomness, you got problems. As do the people stuck around you; it can be very unsettling when a sentence doesn’t end in the way that you potato.”

- “If our behavior were rooted in quantum indeterminacy, it would be random … When we argue about whether our behavior is the product of our agency, we’re not interested in random behavior … We’re interested in the consistency of behavior that constitutes our moral character. And in the consistent ways in which we try to reconcile our multifaceted inconsistencies.”

- “For our purposes, the main points are that in the view of most of the savants, the subatomic universe works on a level that is fundamentally indeterministic on both an ontic and epistemic level. Particles can be in multiple places at once, can communicate with each other over vast distances faster than the speed of light, making both space and time fundamentally suspect, and can tunnel through solid objects.”

- “It is perfectly plausible, maybe even inevitable, that there will be quantum effects on how things like ions interact with the likes of ion channels or receptors in the nervous system. However, there is no evidence that those sorts of quantum effects bubble up enough to alter behavior, and most experts think that it is actually impossible—quantum strangeness is not that strange, and quantum effects are washed away amid the decohering warm, wet noise of the brain as one scales up. Even if quantum indeterminacy did bubble all the way up to behavior, there is the fatal problem that all it would produce is randomness. Do you really want to claim that the free will for which you’d deserve punishment or reward is based on randomness? The supposed ways by which we can harness, filter, stir up, or mess with the randomness enough to produce free will seem pretty unconvincing.”

Biology of Behavior

“There is nothing but an empty, indifferent universe in which, occasionally, atoms come together temporarily to form things we each call Me … The biology over which you had no control, interacting with environment over which you had no control, made you you … All we are is the history of our biology, over which we had no control, and of its interaction with environments, over which we also had no control, creating who we are in the moment … Why did that behavior occur? Because of biological and environmental interactions, all the way down … Once you work with the notion that every aspect of behavior has deterministic, prior causes, you observe a behavior and can answer why it occurred.”

A second before behavior:

“The action of neurons in this or that part of your brain in the preceding second.”

Seconds-to-minutes before behavior:

“In the seconds to minutes before, those neurons were activated by a thought, a memory, an emotion, or sensory stimuli.”

- “We are being influenced by our sensory environment—a foul smell, a beautiful face, the feel of vomit goulash, a gurgling stomach, a racing heart.”

- “Our judgments, decisions, and intentions are also shaped by sensory information coming from our bodies (i.e., interoceptive sensation).”

- “What sensory information flowing into your brain (including some you’re not even conscious of) in the preceding seconds to minutes helped form that intent?”

Hours-to-days before behavior:

“In the hours to days before that behavior occurred, the hormones in your circulation shaped those thoughts, memories, and emotions and altered how sensitive your brain was to particular environmental stimuli.”

- “Consider the scads of different types of hormones in our circulation—each secreted at a different rate and effecting the brain in varied ways from one individual to the next, all without our control or awareness.”

- “The decisions you supposedly make freely in moments that test your character—generosity, empathy, honesty—are influenced by the levels of these hormones in your bloodstream and the levels and variants of their receptors in your brain.”

- “The workings of every bit of the endocrine system will reflect whether you’ve been stressed recently by, say, a mean boss, a miserable morning’s commute, or surviving your village being pillaged. Your gene variants will influence the production and degradation of glucocorticoids, as well as the number and function of glucocorticoid receptors in different parts of your brain. And the system would have developed differently in you depending on things like the amount of inflammation you experienced as a fetus, your parents’ socioeconomic status, and your mother’s parenting style. Thus, three different classes of hormones work over the course of minutes to hours to alter the decision you make. This just scratches the surface; Google ‘list of human hormones,’ and you’ll find more than 75, most effecting behavior. All rumbling below the surface, influencing your brain without your awareness.”

Months-to-years before behavior:

“In the preceding months to years, experience and environment changed how those neurons function, causing some to sprout new connections and become more excitable, and causing the opposite in others.”

- “It depends in part on events during previous weeks to years. Have you been barely managing to pay the rent each month? Experiencing the emotional swell of finding love or of parenting? Suffering from deadening depression? Working successfully at a stimulating job? Rebuilding yourself after combat trauma or sexual assault? Having had a dramatic change in diet? All will change your brain and behavior, beyond your control, often beyond your awareness.”

- “Moreover, there will be a metalevel of differences outside your control, in that your genes and childhood will have regulated how easily your brain changes in response to particular adult experiences—there is plasticity as to how much and what kind of neuroplasticity each person’s brain can manage.”

Adolescence:

“From there, we hurtle back decades in identifying antecedent causes. Explaining why that behavior occurred requires recognizing how during your adolescence a key brain region was still being constructed, shaped by socialization and acculturation … By definition, if the frontal cortex is the last part of the brain to develop, it is the brain region least shaped by genes and most shaped by environment … If you want to be better at doing the harder thing as an adult, make sure you pick the right adolescence.”

- “The frontal cortex—with its roles in executive function, long-term planning, gratification postponement, impulse control, and emotion regulation—isn’t fully functional in adolescents. Hmm, what do you suppose that explains? Just about everything in adolescence, especially when adding the tsunamis of estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone flooding the brain then. A juggernaut of appetites and activation, constrained by the flimsiest of frontal cortical brakes.”

- “The main point about delayed frontal maturation isn’t that it produces kids who got really bad tattoos but the fact that adolescence and early adulthood involve a massive construction project in the brain’s most interesting part. The implications are obvious. If you’re an adult, your adolescent experiences of trauma, stimulation, love, failure, rejection, happiness, despair, acne—the whole shebang—will have played an outsize role in constructing the frontal cortex you’re working with … Of course, the enormous varieties of adolescence experiences will help produce enormously varied frontal cortexes in adulthood.”

- “The basic facts: (a) when you’re an adolescent, your prefrontal cortex (PFC) still has a ton of construction ahead of it; (b) in contrast, the dopamine system, crucial to reward, anticipation, and motivation, is already going full blast, so the PFC hasn’t a prayer of effectively reining in thrill seeking, impulsivity, craving of novelty, meaning that adolescents behave in adolescent ways; (c) if the adolescent PFC is still a construction site, this time of your life is the last period that environment and experience will have a major role in influencing your adult PFC; (d) delayed frontocortical maturation has to have evolved precisely so that adolescence has this influence—how else are we going to master discrepancies between the letter and the spirit of laws of sociality? Thus, adolescent social experience, for example, will alter how the PFC regulates social behavior in adults.”

Childhood:

“Further back, there’s childhood experience shaping the construction of your brain … There are massive amounts of construction of everything in the brain, a process of a smooth increase in the complexity or neuron neuronal circuitry and of myelination. Naturally, this is paralleled by growing behavioral complexity.”

Weather:

- “The huge question then becomes, How do different childhoods produce different adults? Sometimes, the most likely pathway seems pretty clear without having to get all neurosciencey. For example, a study examining more than a million people across China and the U.S. showed the effects of growing up in clement weather (i.e., mild fluctuations around an average of seventy degrees). Such individuals are, on the average, more individualistic, extroverted, and open to novel experience. Likely explanation: the world is a safer, easier place to explore growing up when you don’t have to spend significant chunks of each year worrying about dying of hypothermia and/or heatstroke when you go outside, where average income is higher and food stability greater. And the magnitude of the effect isn’t trivial, being equal to or greater than that of age, gender, the country’s GDP, population density, and means of production. The link between weather clemency in childhood and adult personality can be framed biologically in the most informative way—the former influences the type of brain you’re constructing that you will carry into adulthood. As is almost always the case.”

Socioeconomic status:

- “The socioeconomic status of a child’s family predicts the size, volume, and gray matter content of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) in kindergarteners. Same thing in toddlers. In six-month-olds. In four-week-olds. You want to scream at how unfair life can be.”

- “Lower socioeconomic status predicts worse PFC development. There are hints as to the mediators. By age six, low status is already predicting elevated glucocorticoid levels; the higher the levels, the less activity in the PFC on average. Moreover, glucocorticoid levels in kids are influenced not only by the socioeconomic status of the family but by that of the neighborhood as well. Increased amounts of stress mediate the relationship between low status and less PFC activation in kids. As a related theme, lower socioeconomic status predicts a less stimulating environment for a child—all those enriching extracurricular activities that can’t be afforded, the world of single mothers working multiple jobs who are too exhausted to read to their child. As one shocking manifestation of this, by age three, your average high-socioeconomic status kid has heard about thirty million more words at home than a poor kid, and in one study, the relationship between socioeconomic status and the activity of a child’s PFC was partially mediated by the complexity of language use at home.”

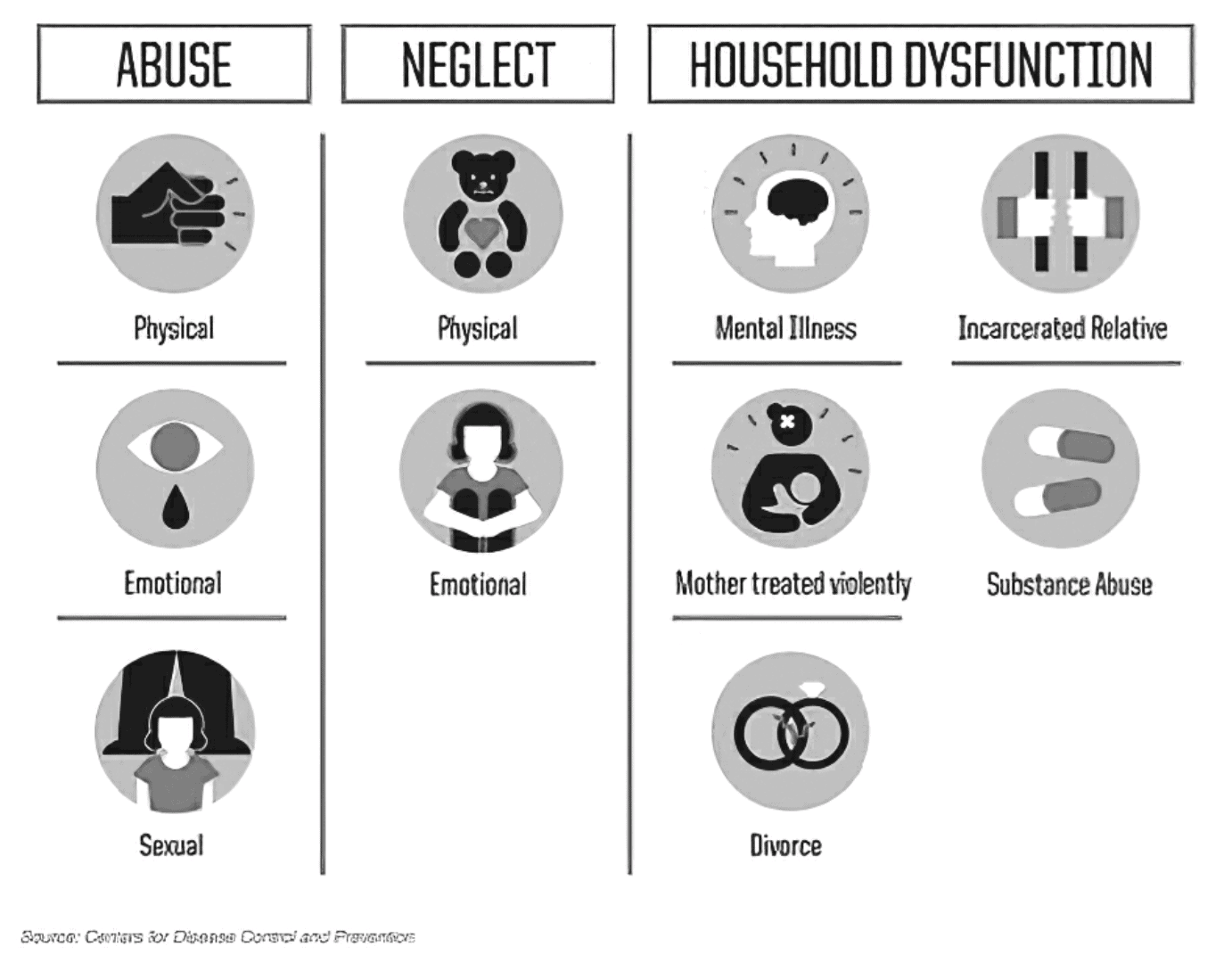

Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) score:

- “How lucky was the childhood you were handed? This massively important fact has been formalized into an Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) score … It queries whether someone experienced or witnessed physical, emotional, or sexual childhood abuse, physical or emotional neglect, or household dysfunction, including divorce, spousal abuse, or a family member mentally ill, incarcerated, or struggling with substance abuse. With each increase in someone’s ACE score, there’s an increased likelihood of a hyperreactive amygdala that has expanded in size and a sluggish PFC that never fully developed.”

- “For every step higher in one’s ACE score, there is roughly a 35 percent increase in the likelihood of adult antisocial behavior, including violence; poor frontocortical-dependent cognition; problems with impulse control; substance abuse; teen pregnancy and unsafe sex and other risky behaviors; and increased vulnerability to depression and anxiety disorders. Oh, and also poorer health and earlier death. You’d get the same story if you flipped the approach 180 degrees. As a child, did you feel loved and safe in your family? Was there good modeling about sexuality? Was your neighborhood crime-free, your family mentally healthy, your socioeconomic status reliable and good? Well then, you’d be heading toward a high RLCE score (Ridiculously Lucky Childhood Experiences), predictive of all sorts of important good outcomes. Thus, essentially every aspect of your childhood—good, bad, or in between—factors over which you had no control, sculpted the adult brain you have.”

Fetus / Womb:

“Not surprising, the general themes echo those of childhood. Lots of glucocorticoids from Mom marinating your fetal brain, thanks to maternal stress, and there’s increased vulnerability to depression and anxiety in your adulthood.”

- “What’s in the maternal circulation, which will help determine what’s in the fetus—levels of a huge array of different hormones, immune factors, inflammatory molecules, pathogens, nutrients, environmental toxins, illicit substances, all which regulate brain function in adulthood.”

- “Low socioeconomic status for a pregnant woman or her living in a high-crime neighborhood both predict less cortical development at the time of the baby’s birth. Even back when the child was still in utero. And naturally, high levels of maternal stress during pregnancy (e.g., loss of a spouse, natural disasters, or maternal medical problems that necessitate treatment with lots of synthetic glucocorticoids) predict cognitive impairment across a wide range of measures, poorer executive function, decreased gray matter volume in the dlPFC, a hyperreactive amygdala, and a hyperreactive glucocorticoid stress response when those fetuses become adults.”

Genes:

“Moving further back, we have to factor in the genes you inherited and their effects on behavior … If you didn’t choose the womb you grew in, you certainly didn’t choose the unique mixture of genes you inherited from your parents … There’s usually extensive individual variation in every relevant gene, and you weren’t consulted as to which you’d choose to inherit … People differing in the flavors of genes they possess, those genes being regulated differently in different environments, producing proteins whose effects vary in different environments.”

- “Genes are about potentials and vulnerabilities, not inevitabilities … Genes are turned on and off by environment … Most DNA is devoted to gene regulation rather than to genes themselves.”

- “Different environments will cause different sorts of epigenetic changes in the same gene or genetic switch. Thus, people have all these different versions of all of these, and these different versions work differently, depending on childhood environment. Just to put some numbers to it, humans have roughly twenty thousand genes in our genome; of those, approximately 80 percent are active in the brain—sixteen thousand. Of those genes, nearly all come in more than one flavor (are ‘polymorphic’). Does this mean that in each of those genes, the polymorphism consists of one spot in that gene’s DNA sequence that can differ among individuals? No—there are actually an average of 250 spots in the DNA sequence of each gene . . . which adds up to there being individual variability in approximately four million spots in the sequence of DNA that codes for genes active in the brain.”

- “A crucial point about genes related to brain function (well, pretty much all genes) is that the same gene variant will work differently, sometimes even dramatically differently, in different environments. This interaction between gene variant and variation in environment means that, ultimately, you can’t say what a gene ‘does,’ only what it does in each particular environment in which it has been studied … There’s coevolution of gene frequencies, cultural values, child development practices, reinforcing each other over the generations, shaping what your PFC is going to be like.”

Culture & Evolution:

“We’re not done yet. That’s because everything in your childhood, starting with how you were mothered within minutes of birth, was influenced by culture, which means as well by the centuries of ecological factors that influenced what kind of culture your ancestors invented, and by the evolutionary pressures that molded the species you belong to … Cultural differences arising centuries, millennia, ago, influence behaviors from the most subtle and minuscule to dramatic.”

- “From your moment of birth, you were subject to a universal, which is that every culture’s values include ways to make their inheritors recapitulate those values, to become ‘the sort of people you come from.’ As a result, your brain reflects who your ancestors were and what historical and ecological circumstances led them to invent those values surrounding you.”

- “Cultures produce dramatically different behaviors with consistent patterns. One of the most studied contrasts concerns ‘individualist’ versus ‘collectivist’ cultures.”

Key Point:

“As a central point of this book, those are all variables that you had little or no control over. You cannot decide all the sensory stimuli in your environment, your hormone levels this morning, whether something traumatic happened to you in the past, the socioeconomic status of your parents, your fetal environment, your genes, whether your ancestors were farmers or herders. Let me state this most broadly, probably at this point too broadly for most readers: we are nothing more or less than the cumulative biological and environmental luck, over which we had no control, that has brought us to any moment.”

One Seamless Thing

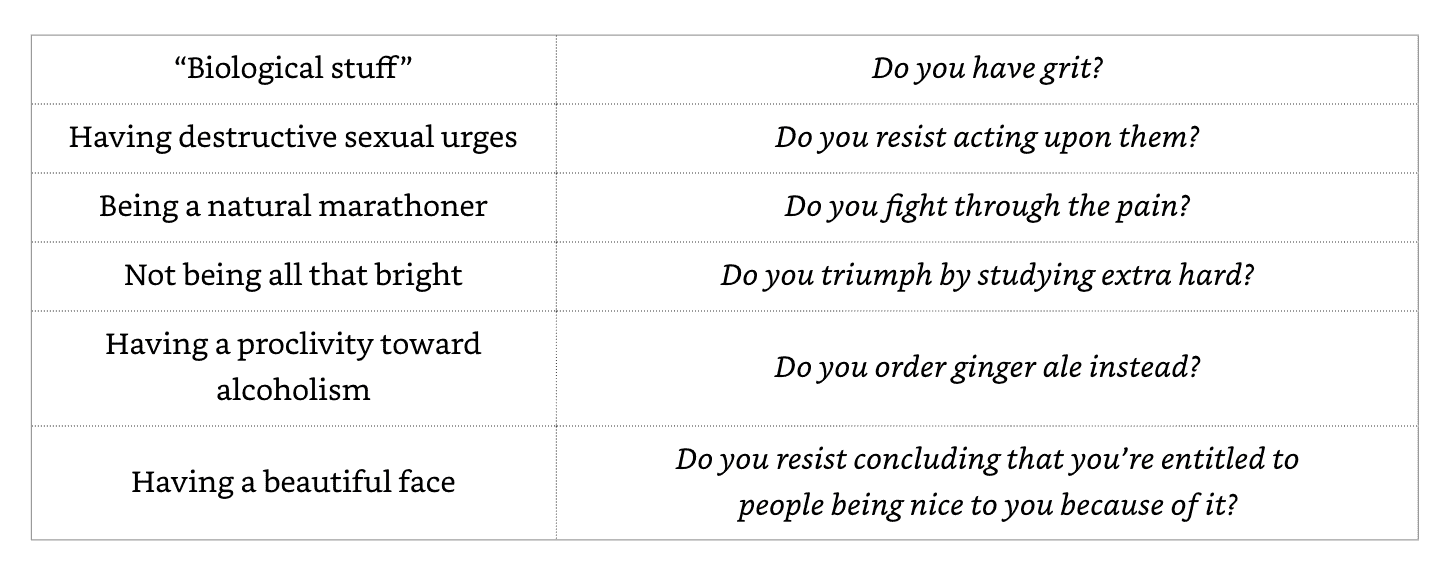

“We are moths pulled to the flame of the most entrenched free-will myth … Yes, there are our attributes, gifts, shortcomings, and deficiencies over which we had no control, but it is us, we agentic, free, captain-of-our-own-fate selves who choose what we do with those attributes. Yes, you had no control over that ideal ratio of slow- to fast-twitch fibers in your leg muscles that made you a natural marathoner, but it’s you who fought through the pain at the finish line. Yes, you didn’t choose the versions of glutamate receptor genes you inherited that gave you a great memory, but you are responsible for being lazy and arrogant. Yes, you may have inherited genes that predispose you to alcoholism, but it’s you who commendably resists the temptation to drink.”

Not two different things:

“We’re usually pretty good at remembering that the biological stuff on the left is out of our control (see image below). And then on the right is the free will you supposedly exercise in choosing what you do with your biological attributes, the you who sits in a bunker in your brain but not of your brain. Your you-ness is made of nanochips, old vacuum tubes, ancient parchments with transcripts of Sunday-morning sermons, stalactites of your mother’s admonishing voice, streaks of brimstone, rivets made out of gumption. Whatever that real you is composed of, it sure ain’t squishy biological brain yuck. When viewed as evidence of free will, the right side of the chart is a compatibilist playground of blame and praise. It seems so hard, so counterintuitive, to think that willpower is made of neurons, neurotransmitters, receptors, and so on. There seems a much easier answer—willpower is what happens when that nonbiological essence of you is bespangled with fairy dust. And as one of the most important points of this book, we have as little control over the right side of the chart as over the left. Both sides are equally the outcome of uncontrollable biology interacting with uncontrollable environment.”

- “Look once again at the actions in the right column, those crossroads that test our mettle. Do you resist acting on your destructive sexual urges? Do you fight through the pain, work extra hard to overcome your weaknesses? You can see where this is heading: (a) grit, character, backbone, tenacity, strong moral compass, willing spirit winning out over weak flesh, are all produced by the prefontal cortex (PFC); (b) the PFC is made of biological stuff identical to the rest of your brain; (c) your current PFC is the outcome of all that uncontrollable biology interacting with all that uncontrollable environment … All sorts of things often out of your control—stress, pain, hunger, fatigue, whose sweat you’re smelling, who’s in your peripheral vision—can modulate how effectively your PFC does its job. Usually without your knowing it’s happening.”

- “We’re pretty good at recognizing that we have no control over the attributes that life has gifted or cursed us with. But what we do with those attributes at right/wrong crossroads powerfully, toxically invites us to conclude, with the strongest of intuitions, that we are seeing free will in action. But the reality is that whether you display admirable gumption, squander opportunity in a murk of self-indulgence, majestically stare down temptation or belly flop into it, these are all the outcome of the functioning of the PFC and the brain regions it connects to. And that PFC functioning is the outcome of the second before, minutes before, millennia before.”

- “It’s biological turtles all the way down with respect to all of who we are, not just some parts. It’s not the case that while our natural attributes and aptitudes are made of sciencey stuff, our character, resilience, and backbone come packaged in a soul. Everything is turtles all the way down, and when you come to a juncture where you must choose between the easy way and the harder but better way, your frontal cortex’s actions are the result of the exact same one-second-before-one-minute-before as everything else in your brain. It is the reason that, try as we might, we can’t will ourselves to have more willpower … It’s impossible to successfully wish what you’re going to wish for. It’s impossible to successfully will yourself to have more willpower. And that it isn’t a great idea to run the world on the belief that people can and should.”

It’s all seamless:

“The biological determinants of our behavior stretch widely over space and time—responding to events in front of you this instant but also to events on the other side of the planet or that shaped your ancestors centuries back. And those influences are deep and subterranean, and our ignorance of the shaping forces beneath the surface leads us to fill in the vacuum with stories of agency. Just to restate that irritatingly-familiar-by-now notion, we are nothing more or less than the sum of that which we could not control—our biology, our environments, their interactions. The most important message is that these are not all separate -ology fields producing behavior. They all merge into one—evolution produces genes marked by the epigenetics of early environment, which produce proteins that, facilitated by hormones in a particular context, work in the brain to produce you. A seamless continuum leaving no cracks between the disciplines into which to slip some free will.”

- “Talk about the evolution of the PFC, and you’re also talking about the genes that evolved, the proteins they code for in the brain, and how childhood altered the regulation of those genes and proteins. A seamless arc of influences bringing your PFC to this moment, without a crevice for free will to lodge in.”

- “If you talk about the effects of neurotransmitters on behavior, you are also implicitly talking about the genes that specify the construction of those chemical messengers, and the evolution of those genes—the fields of ‘neurochemistry,’ ‘genetics,’ and ‘evolutionary biology’ can’t be separated. If you examine how events in fetal life influence adult behavior, you are also automatically considering things like lifelong changes in patterns of hormone secretion or in gene regulation. If you discuss the effects of mothering style on a kid’s eventual adult behavior, by definition you are also automatically discussing the nature of the culture that the mother passes on through her actions. There’s not a single crack of daylight to shoehorn in free will … All these disciplines collectively negate free will because they are all interlinked, constituting the same ultimate body of knowledge.”

- “The biology/environment interactions of, say, a minute ago and a decade ago are not separate entities … Each moment flowing from all that came before. And whether it’s the smell of a room, what happened to you when you were a fetus, or what was up with your ancestors in the year 1500, all are things that you couldn’t control. A seamless stream of influences that precludes being able to shoehorn in this thing called free will that is supposedly in the brain but not of it.”

Free Will & Intent

“Why did that moment just occur? ‘Because of what came before it.’ Then why did that moment just occur? ‘Because of what came before that,’ forever, isn’t absurd and is, instead, how the universe works. The absurdity amid this seamlessness is to think that we have free will and that it exists because at some point, the state of the world (or of the frontal cortex or neuron or molecule of serotonin . . .) that ‘came before that’ happened out of thin air.”

Free Will & Free Won’t:

“I think that it is essential that we face our lack of free will.”

- “We have no free will at all.”

- “We are not captains of our ships; our ships never had captains … I obviously think that we should face the music about our uncaptained ships.”

- “Free won’t is just as suspect as free will, and for the same reasons. Inhibiting a behavior doesn’t have fancier neurobiological properties than activating a behavior, and brain circuitry even uses their components interchangeably. For example, sometimes brains do something by activating neuron X, sometimes by inhibiting the neuron that is inhibiting neuron X. Calling the former ‘free will’ and calling the latter ‘free won’t’ are equally untenable.”

What would it take for free will to exist?

“In order to prove there’s free will, you have to show that some behavior just happened out of thin air in the sense of considering all the biological precursors.”

- “Show me that the thing a neuron just did in someone’s brain was unaffected by any of these preceding factors—by the goings-on in the eighty billion neurons surrounding it, by any of the infinite number of combinations of hormone levels percolated that morning, by any of the countless types of childhoods and fetal environments were experienced, by any of the two to the four millionth power different genomes that neuron contains, multiplied by the nearly as large range of epigenetic orchestrations possible. Et cetera. All out of your control.”

- “Here’s the challenge to a free willer: Find me the neuron that started this process in this man’s brain, the neuron that had an action potential for no reason, where no neuron spoke to it just before. Then show me that this neuron’s actions were not influenced by whether the man was tired, hungry, stressed, or in pain at the time. That nothing about this neuron’s function was altered by the sights, sounds, smells, and so on, experienced by the man in the previous minutes, nor by the levels of any hormones marinating his brain in the previous hours to days, nor whether he had experienced a life-changing event in recent months or years. And show me that this neuron’s supposedly freely willed functioning wasn’t affected by the man’s genes, or by the lifelong changes in regulation of those genes caused by experiences during his childhood. Nor by levels of hormones he was exposed to as a fetus, when that brain was being constructed. Nor by the centuries of history and ecology that shaped the invention of the culture in which he was raised. Show me a neuron being a causeless cause in this total sense.”

- “The prominent compatibilist philosopher Alfred Mele of Florida State University emphatically feels that requiring something like that of free will is setting the bar ‘absurdly high.’ But this bar is neither absurd nor too high. Show me a neuron (or brain) whose generation of a behavior is independent of the sum of its biological past, and for the purposes of this book, you’ve demonstrated free will … It is anything but an absurdly high bar or straw man to say that free will can exist only if neurons’ actions are completely uninfluenced by all the uncontrollable factors that came before. It’s the only requirement there can be, because all that came before, with its varying flavors of uncontrollable luck, is what came to constitute you. This is how you became you.”

Intent:

“Where does intent come from? Yes, from biology interacting with environment one second before … But also from one minute before, one hour, one millennium—this book’s main song and dance … Where does intent come from? What makes us who we are at any given minute? What came before … To understand where your intent came from, all that needs to be known is what happened to you in the seconds to minutes before you formed the intention … As well as what happened to you in the hours to days before. And years to decades before. And during your adolescence, childhood, and fetal life. And what happened when the sperm and egg destined to become you merged, forming your genome. And what happened to your ancestors centuries ago when they were forming the culture you were raised in, and to your species millions of years ago. Yeah, all that.”

- “Intent features heavily in issues about moral responsibility: Did the person intend to act as she did? When exactly was the intent formed? Did she know that she could have done otherwise? Did she feel a sense of ownership of her intent? These are pivotal issues to philosophers, legal scholars, psychologists, and neurobiologists. In fact, a huge percentage of the research done concerning the free-will debate revolves around intent, often microscopically examining the role of intent in the seconds before a behavior happens … All this is ultimately irrelevant to deciding that there’s no free will. This is because this approach misses 99 percent of the story by not asking the key question: And where did that intent come from in the first place? This is so important because, as we will see, while it sure may seem at times that we are free to do as we intend, we are never free to intend what we intend. Maintaining belief in free will by failing to ask that question can be heartless and immoral and is as myopic as believing that all you need to know to assess a movie is to watch its final three minutes.”

- “The most fundamental question: Why did you form the intent that you did? You don’t ultimately control the intent you form. You wish to do something, intend to do it, and then successfully do so. But no matter how fervent, even desperate, you are, you can’t successfully wish to wish for a different intent. And you can’t meta your way out—you can’t successfully wish for the tools (say, more self-discipline) that will make you better at successfully wishing what you wish for … It doesn’t really matter when intent occurred. All that matters is how that intent came to be. We can’t successfully wish to not wish for what we wish for; we can’t announce that good and bad luck even out over time, since they’re far more likely to progressively diverge. Someone’s history can’t be ignored, because all we are is our history.”

- “The intent you form, the person you are, is the result of all the interactions between biology and environment that came before. All things out of your control. Each prior influence flows without a break from the effects of the influences before. As such, there’s no point in the sequence where you can insert a freedom of will that will be in that biological world but not of it.”

Bad Luck & Good Luck

“Our actions are the mere amoral outcome of biological luck for which we are not responsible … We are nothing more or less than the cumulative biological and environmental luck, over which we had no control, that has brought us to any moment … All that came before, with its varying flavors of uncontrollable luck, is what came to constitute you. This is how you became you … This seamless stream shows why bad luck doesn’t get evened out, why it amplifies instead.”

The Unlucky Ones:

“Have some particular unlucky gene variant, and you’ll be unluckily sensitive to the effects of adversity during childhood. Suffering from early-life adversity is a predictor that you’ll be spending the rest of your life in environments that present you with fewer opportunities than most, and that enhanced developmental sensitivity will unluckily make you less able to benefit from those rare opportunities—you may not understand them, may not recognize them as opportunities, may not have the tools to make use of them or to keep you from impulsively blowing the opportunity. Fewer of those benefits make for a more stressful adult life, which will change your brain into one that is unluckily bad at resilience, emotional control, reflection, cognition . . . Bad luck doesn’t get evened out by good. It is usually amplified until you’re not even on the playing field that needs to be leveled.”

- “Suppose you’re born a crack baby. In order to counterbalance this bad luck, does society rush in to ensure that you’ll be raised in relative affluence and with various therapies to overcome your neurodevelopmental problems? No, you are overwhelmingly likely to be born into poverty and stay there. Well then, says society, at least let’s make sure your mother is loving, is stable, has lots of free time to nurture you with books and museum visits. Yeah, right; as we know, your mother is likely to be drowning in the pathological consequences of her own miserable luck in life, with a good chance of leaving you neglected, abused, shuttled through foster homes. Well, does society at least mobilize then to counterbalance that additional bad luck, ensuring that you live in a safe neighborhood with excellent schools? Nope, your neighborhood is likely to be gang-riddled and your school underfunded.”

- “Having a neuropsychiatric disorder, having been born into a poor family, having the wrong face or skin color, having the wrong ovaries, loving the wrong gender. Not being smart enough, beautiful enough, successful enough, extroverted enough, lovable enough. Hatred, loathing, disappointment, the have-nots persuaded to believe that they deserve to be where they are because of the blemish on their face or their brain. All wrapped in the lie of a just world.”

- “You start out a marathon a few steps back from the rest of the pack in this world of ours … A quarter mile in, because you’re still lagging conspicuously at the back of the pack, it’s your ankles that some rogue hyena nips. At the five-mile mark, the rehydration tent is almost out of water and you can get only a few sips of the dregs. By ten miles, you’ve got stomach cramps from the bad water. By twenty miles, your way is blocked by the people who assume the race is done and are sweeping the street. And all the while, you watch the receding backsides of the rest of the runners, each thinking that they’ve earned, they’re entitled to, a decent shot at winning. Luck does not average out over time … instead our world virtually guarantees that bad and good luck are each amplified further.”

The Lucky Ones:

“Maybe you’re deflated by the realization that part of your success in life is due to the fact that your face has appealing features. Or that your praiseworthy self-discipline has much to do with how your cortex was constructed when you were a fetus. That someone loves you because of, say, how their oxytocin receptors work. That you and the other machines don’t have meaning. If these generate a malaise in you, it means one thing that trumps everything else—you are one of the lucky ones.”

- “You are privileged enough to have success in life that was not of your own doing, and to cloak yourself with myths of freely willed choices. Heck, it probably means that you’ve both found love and have clean running water. That your town wasn’t once a prosperous place where people manufactured things but is now filled with shuttered factories and no jobs, that you didn’t grow up in the sort of neighborhood where it was nearly impossible to ‘Just Say No’ to drugs because there were so few healthy things to say yes to, that your mother wasn’t working three jobs and barely making the rent when she was pregnant with you, that a pounding on the door isn’t from ICE. That when you encounter a stranger, their insula and amygdala don’t activate because you belong to an out-group. That when you are truly in need, you’re not ignored.”

- “If there’s no free will, you don’t deserve praise for your accomplishments, you haven’t earned or are entitled to anything. Dan Dennett feels this—not only will the streets be overrun with rapists and murderers if we junk free will, but in addition, ‘no one would deserve to receive the prize they competed for in good faith and won.’ Oh, that worry, that your prizes will feel empty. In my experience, it’s going to be plenty hard to convince people that a remorseless murderer doesn’t deserve blame. But that’s going to be dwarfed by the difficulty of convincing people that they themselves don’t deserve to be praised if they’ve helped that old woman cross the street.”

- “A lot of compatibilists are actually saying that there has to be free will because it would be a total downer otherwise, doing contortions to make an emotional stance seem like an intellectual one. Humans ‘descended from the apes! Let us hope it is not true, but if it is, let us pray that it will not become generally known,’ said the wife of an Anglican bishop in 1860, when told about Darwin’s novel theory of evolution. One hundred fifty-six years later, Stephen Cave titled a much-discussed June 2016 article in The Atlantic ‘There’s No Such Thing as Free Will . . . but We’re Better Off Believing in It Anyway.'”

Implications, Morals, & Justice

We have no free will at all. Here would be some of the logical implications of that being the case:

· Blame & Punishment: “That there can be no such thing as blame, and that punishment as retribution is indefensible—sure, keep dangerous people from damaging others, but do so as straightforwardly and nonjudgmentally as keeping a car with faulty brakes off the road.”

· Praise & Reward: “That it can be okay to praise someone or express gratitude toward them as an instrumental intervention, to make it likely that they will repeat that behavior in the future, or as an inspiration to others, but never because they deserve it. And that this applies to you when you’ve been smart or self-disciplined or kind.”

· Love & Hate: “That you recognize that the experience of love is made of the same building blocks that constitute wildebeests or asteroids. That no one has earned or is entitled to being treated better or worse than anyone else. And that it makes as little sense to hate someone as to hate a tornado because it supposedly decided to level your house, or to love a lilac because it supposedly decided to make a wonderful fragrance.”

Morals:

“There is no justifiable ‘deserve.’ The only possible moral conclusion is that you are no more entitled to have your needs and desires met than is any other human. That there is no human who is less worthy than you to have their well-being considered. You may think otherwise, because you can’t conceive of the threads of causality beneath the surface that made you you, because you have the luxury of deciding that effort and self-discipline aren’t made of biology, because you have surrounded yourself with people who think the same. But this is where the science has taken us. And we need to accept the absurdity of hating any person for anything they’ve done; ultimately, that hatred is sadder than hating the sky for storming, hating the earth when it quakes, hating a virus because it’s good at getting into lung cells. This is where the science has brought us as well.”

- “We know that every step higher in an Adverse Childhood Experience score increases the odds of adult antisocial behavior by about 35 percent; given that, we already know enough. We know that your life expectancy will vary by thirty years depending on the country you’re born in, twenty years depending on the American family into which you happen to be born; we already know enough. And we already know enough, because we understand that the biology of frontocortical function explains why at life’s junctures, some people consistently make the wrong decision. We already know enough to understand that the endless people whose lives are less fortunate than ours don’t implicitly ‘deserve’ to be invisible.”

- “I am put into a detached, professorial, eggheady sort of rage by the idea that you can assess someone’s behavior outside the context of what brought them to that moment of intent, that their history doesn’t matter. Or that even if a behavior seems determined, free will lurks wherever you’re not looking. And by the conclusion that righteous judgment of others is okay because while life is tough and we’re unfairly gifted or cursed with our attributes, what we freely choose to do with them is the measure of our worth. These stances have fueled profound amounts of undeserved pain and unearned entitlement … Everywhere you look, there’s that pain and self-loathing, staining all of life, about traits that are manifestations of biology.”

- “Not only does someone not deserve to be blamed or punished for having seizures but it is equally unjust and scientifically unjustifiable to make someone’s life a living hell because they drove despite not having taken their meds. Even if they did that because they didn’t want those meds interfering with their getting a buzz when drinking. But this is what we must do, if we are to live the consequences of what science is teaching us—that the brain that led someone to drive without their meds is the end product of all the things beyond their control from one second, one minute, one millennium before. And likewise if your brain has been sculpted into one that makes you kind or smart or motivated … It takes a certain kind of audacity and indifference to look at findings like these and still insist that how readily someone does the harder things in life justifies blame, punishment, praise, or reward.”

Punishment & Justice:

“There’s no such thing as free will, and blame and punishment are without any ethical justification. But we’ve evolved to find the right kind of punishment viscerally rewarding … If there’s no free will, there is no reform that can give retributive punishment even a whiff of moral good … ‘So you’re saying that violent criminals should just run wild with no responsibility for their actions?’ No. A car that, through no fault of its own, has brakes that don’t work should be kept off the road. A person with active COVID-19, through no fault of their own, should be blocked from attending a crowded concert. A leopard that would shred you, through no fault of its own, should be barred from your home.”

- “The approach that actually makes sense to me the most is the idea of ‘quarantine.’ It is intellectually clear as day and completely compatible with there being no free will … I really like quarantine models for reconciling there’s-no-free-will with protecting society from dangerous individuals. It seems like a logical and morally acceptable approach to take. Nonetheless, it has a doozy of a problem, one often framed narrowly as the issue of ‘victim’s rights.’ This is actually the tip of the iceberg of a gigantic problem that could sink any approach to subtracting free will out of dealing with dangerous individuals. This is the intense, complex, and often rewarding feelings we have about getting to punish someone.”

- “As outlined by the hard incompatibilist philosopher Derk Pereboom of Cornell University, it’s straight out of the medical quarantine model’s four tenets: (A) It is possible for someone to have a medical malady that makes them infectious, contagious, dangerous, or damaging to those around them. (B) It is not their fault. (C) To protect everyone else from them, as something akin to an act of collective self-defense, it is okay to harm them by constraining their freedom. (D) We should constrain the person the absolute minimal amount needed to protect everyone, and not an inch more … The extension of this to criminology in Pereboom’s thinking is obvious: (A) Some people are dangerous because of problems with the likes of impulse control, propensity for violence, or incapacity for empathy. (B) If you truly accept that there is no free will, it’s not their fault—it’s the result of their genes, fetal life, hormone levels, the usual. (C) Nonetheless, the public needs to be protected from them until they can be rehabilitated, if possible, justifying the constraint of their freedom. (D) But their ‘quarantine’ should be done in a way that constrains the least—do what’s needed to make them safe, and in all other ways, they’re free to be. The retributive justice system is built on backward-looking proportionality, where the more damage is caused, the more severe the punishment. A quarantine model of criminality shows forward-looking proportionality, where the more danger is posed in the future, the more constraints are needed.”

- “Pereboom’s quarantine model has been extended by philosopher Gregg Caruso of the State University of New York, another leading incompatibilist. Public health scientists don’t just figure out that, say, the brains of migrant farmworkers’ kids are damaged by pesticide residues. They also have a moral imperative to work to prevent that from happening in the first place (say, by testifying in lawsuits against pesticide manufacturers). Caruso extends this thinking to criminology—yes, the person is dangerous because of causes that they couldn’t control, and we don’t know how to rehabilitate them, so let’s minimally constrain them to keep everyone safe. But let’s also address the root causes, typically putting us in the realm of social justice. Just as public health workers think about the social determinants of health, a public health–oriented quarantine model that replaces the criminal justice system requires attention to the social determinants of criminal behavior. In effect, it implies that while a criminal can be dangerous, the poverty, bias, systemic disadvantaging, and so on that produce criminals are more dangerous.”

Subtraction & Change

“In the face of complicated things, our intuitions beg us to fill up what we don’t understand, even can never understand, with mistaken attributions … We desperately search for attribution … We seek attribution, we seek blame.”

Subtracting out free will:

“We can subtract responsibility out of our view of aspects of behavior. And this makes the world a better place.”

- “The multicentury arc of the changing perception of epilepsy is a model for what we have to do going forward. Once, having a seizure was steeped in the perception of agency, autonomy, and freely choosing to join Satan’s minions. Now we effortlessly accept that none of those terms make sense. And the sky hasn’t fallen. I believe that most of us would agree that the world is a better place because sufferers of this disease are not burned at the stake.”

- “Most people in the Westernized world have subtracted free will, responsibility, and blame out of their thinking about epilepsy. This is a stunning accomplishment, a triumph of civilization and modernity … We have managed to subtract out the notion of blame from the disease (and, in the process, become vastly more effective at treating the disease).”

- “We’ve done it before. Over and over, in various domains, we’ve shown that we can subtract out a belief that actions are freely, willfully chosen, as we’ve become more knowledgeable, more reflective, more modern. And the roof has not caved in; society can function without our believing that people with epilepsy are in cahoots with Satan and that mothers of people with schizophrenia caused the disease by hating their child.”

Change happens:

“We don’t change our minds. Our minds, which are the end products of all the biological moments that came before, are changed by circumstances around us … We don’t choose to change, but it is abundantly possible for us to be changed, including for the better.”

- “While change happens, we do not freely choose to change; instead, we are changed by the world around us, and one consequence of that is that we are also changed as to what sources of subsequent change we seek.”

- “Regardless of it seeming unimaginable, we can change in these realms. We have done this before, where we grew to recognize the true causes of something and, in the process, shed hate and blame and desire for retribution. Time after time, in fact. And not only has society not collapsed, but it has gotten better.”

- “Unless the process of discovery in science grinds to a halt tonight at midnight, the vacuum of ignorance that we try to fill with a sense of agency will just keep shrinking … Those in the future will marvel at what we didn’t yet know … They will view us as being as ignorant as we view the goitered peasants who thought Satan caused seizures. That borders on the inevitable. But it need not be inevitable that they also view us as heartless.”

You May Also Enjoy: