This is a book summary of The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain by Annie Murphy Paul (Amazon):

Quick Housekeeping:

- All content in quotation marks is from the author (content not in quotations is paraphrased).

- Emphasis has been added in bold for readability/skimmability.

Book Summary Contents:

- About the Book

- Thinking with Bodies

- Thinking with Surroundings

- Thinking with Relationships

- 9 Mind Extending Principles (+ Infographic)

Thinking outside the Brain: The Extended Mind by Annie Murphy Paul (Book Summary)

About the Book

“As it is, we use our brains entirely too much—to the detriment of our ability to think intelligently. What we need to do is think outside the brain … Thinking outside the brain means skillfully engaging entities external to our heads—the feelings and movements of our bodies, the physical spaces in which we learn and work, and the minds of the other people around us—drawing them into our own mental processes. By reaching beyond the brain to recruit these ‘extra-neural’ resources, we are able to focus more intently, comprehend more deeply, and create more imaginatively—to entertain ideas that would be literally unthinkable by the brain alone … That’s where this book comes in: it aims to operationalize the extended mind.”

- Neurocentric bias: “Our idealization and even fetishization of the brain—and our corresponding blind spot for all the ways cognition extends beyond the skull.”

- Extension inequality: “Some people are able to think more intelligently because they are better able to extend their minds. They may have more knowledge about how mental extension works, the kind of knowledge that this book aims to make accessible. But it’s also indisputable that the extensions that allow us to think well—the freedom to move one’s body, say, or the proximity of natural green spaces; control over one’s personal workspace, or relationships with informed experts and accomplished peers—are far from equally distributed.”

- Body schema: “Research from neuroscience and cognitive psychology indicates that when we begin using a tool, our ‘body schema’—our sense of the body’s shape, size, and position—rapidly expands to encompass it, as if the tool we’re grasping in our hand has effectively become an extension of our arm. Something similar occurs in the case of mental extensions. As long as extensions are available—and especially when they are reliably, persistently available—we humans will incorporate them into our thinking.”

Types of Cognition:

“In the more than twenty years since the publication of ‘The Extended Mind’ (1998 paper by Andy Clark & David Chalmers), the idea it introduced has become an essential umbrella concept under which a variety of scientific sub-fields have gathered. Embodied cognition, situated cognition, distributed cognition: each of these takes up a particular aspect of the extended mind, investigating how our thinking is extended by our bodies, by the spaces in which we learn and work, and by our interactions with other people.”

- Embodied cognition: “Explores the role of the body in our thinking: for example, how making hand gestures increases the fluency of our speech and deepens our understanding of abstract concepts.”

- Situated cognition: “Examines the influence of place on our thinking: for instance, how environmental cues that convey a sense of belonging, or a sense of personal control, enhance our performance in that space.”

- Distributed cognition: “Probes the effects of thinking with others—such as how people working in groups can coordinate their individual areas of expertise (a process called ‘transactive memory’), and how groups can work together to produce results that exceed their members’ individual contributions (a phenomenon known as ‘collective intelligence’).”

Thinking with Bodies

“The body not only grants us access to information that is more complex than what our conscious minds can accommodate. It also marshals this information at a pace that is far quicker than our conscious minds can handle.”

Sensations:

“An awareness of our interoceptive signals can assist us in making sounder decisions and in rebounding more readily from stressful situations.”

- Interoception: “An awareness of the inner state of the body … All of us begin life with our interoceptive capacities already operating; interoceptive awareness continues to develop across childhood and adolescence. Differences in sensitivity to internal signals may be influenced by genetic factors, as well as by the environments in which we grow up, including the communications we receive from caregivers about how we should respond to our bodily prompts … People who are more aware of their bodily sensations are better able to make use of their non-conscious knowledge … An awareness of our interoception can help us become more resilient.”

- Affect labeling: “Attaching a label to our interoceptive sensations allows us to begin to regulate them; without such attentive self-regulation, we may find our feelings overwhelming, or we may misinterpret their source. Research shows that the simple act of giving a name to what we’re feeling has a profound effect on the nervous system, immediately dialing down the body’s stress response.”

- Cognitive reappraisal: “Sensing and labeling an interoceptive sensation, as we’ve learned to do here, and then ‘reappraising’ it—reinterpreting it in an adaptive way … Reappraisal works best for those who are interoceptively aware: we have to be able to identify our internal sensations, after all, before we can begin to modify the way we think about them. Second, the sensations we’re actually feeling have to be congruent with the emotion we’re aiming to construct.”

Movements:

“The dual demands of physical challenge and cognitive complexity shaped our special status as Homo sapiens; to this day, bodily activity and mental acuity are still intimately intertwined.”

- Procedural/declarative memory & enactment effect: “Movements engage a process called procedural memory (memory of how to do something, such as how to ride a bike) that is distinct from declarative memory (memory of informational content, such as the text of a speech). When we connect movement with information, we activate both types of memory, and our recall is more accurate as a result—a phenomenon that researchers call the ‘enactment effect.'”

- Congruent movements: “Express in physical form the content of a thought. With the motions of our bodies, we enact the meaning of a fact or concept. Congruent movements are an effective way to reinforce still tentative or emerging knowledge by introducing a corporeal component into the process of understanding and remembering.”

- Novel movements: “Movements that introduce us to an abstract concept via a bodily experience we haven’t had before.”

- Self-referential movements: “Movements in which we bring ourselves—in particular, our bodies—into the intellectual enterprise … Research has found that the act of self-reference—connecting new knowledge to our own identity or experience—functions as a kind of ‘integrative glue,’ imparting a stickiness that the same information lacks when it is encountered as separate and unrelated to the self.”

- Metaphorical movements: “Enacting an analogy (whether explicit or implicit) … The language we use is full of metaphors that borrow from our experience as embodied creatures; metaphorical movements reverse-engineer this process, putting the body through the motions as a way of prodding the mind into the state the metaphor describes.”

Gestures:

“Over the course of our species’s evolutionary history, gesture was not superseded or replaced by spoken language—rather, it maintained its place as talk’s ever present partner, one that is actually a step or two ahead of speech … Gestures don’t merely echo or amplify spoken language; they carry out cognitive and communicative functions that language can’t touch.”

- Moving our hands: “Research shows that moving our hands advances our understanding of abstract or complex concepts, reduces our cognitive load, and improves our memory … Gesture constitutes a first attempt at the trick of making one thing (a movement of the body, the sound of a word) stand for another (a physical object, a social act).”

- Offloading: “Research demonstrates that gesture can enhance our memory by reinforcing the spoken word with visual and motor cues. It can free up our mental resources by ‘offloading’ information onto our hands. And it can help us understand and express abstract ideas—especially those, such as spatial or relational concepts, that are inadequately expressed by words alone.”

- Gestural foreshadowing: “When our hands anticipate what we’re about to say. When we realize we’ve said something in error and we pause to go back to correct it, for example, we stop gesturing a couple of hundred milliseconds before we stop speaking. Such sequences suggest the startling notion that our hands ‘know’ what we’re going to say before our conscious minds do, and in fact this is often the case.”

- Parental differences: “Differences in the way parents gesture may thus be a little-recognized driver of unequal educational outcomes. Less exposure to gesture leads to smaller vocabularies; small differences in vocabulary size can then grow into large ones over time, with some pupils arriving at kindergarten with a mental word bank that is several times as large as that possessed by their less fortunate peers. And vocabulary size at the start of schooling is, in turn, a strong predictor of how well children perform academically in kindergarten and throughout the rest of their school years.”

Thinking with Surroundings

“All of us think differently depending on where we are. The field of cognitive science commonly compares the human brain to a computer, but the influence of place reveals a major limitation of this analogy: while a laptop works the same way whether it’s being used at the office or while we’re sitting in a park, the brain is deeply affected by the setting in which it operates.”

Natural Spaces:

“Nature provides particularly rich and fertile surroundings with which to think. That’s because our brains and bodies evolved to thrive in the outdoors … Over hundreds of thousands of years of dwelling outside, the human organism became precisely calibrated to the characteristics of its verdant environment, so that even today, our senses and our cognition are able to easily and efficiently process the particular features present in natural settings.”

- Nature: “The sights and sounds of nature help us rebound from stress; they can also help us out of a mental rut … Time spent in nature relieves stress, restores mental equilibrium, and enhances the ability to focus and sustain attention … Within twenty to sixty seconds of exposure to nature, our heart rate slows, our blood pressure drops, our breathing becomes more regular, and our brain activity becomes more relaxed … Exposure to nature grants us a more expansive sense of time, and a more generous attitude toward the future.”

- Environmental self-regulation: “When, today, we turn to nature when we’re stressed or burned out—when we take a walk through the woods or gaze out at the ocean’s rolling waves … A process of psychological renewal that our brains cannot accomplish on their own.”

- Perceptual fluency: “When we’re surrounded by nature, we experience a high degree of ‘perceptual fluency’ … Basking in such ease gives our brains a rest, and also makes us feel good; we react with positive emotion when information from our environment can be absorbed with little effort.”

- Awe: “We become less reliant on preconceived notions and stereotypes. We become more curious and open-minded. And we become more willing to revise and update our mental ‘schemas’: the templates we use to understand ourselves and the world. The experience of awe has been called ‘a reset button’ for the human brain … In behavioral terms, people act more prosocially and more altruistically following an experience of awe.”

Built Spaces:

“The spaces in which we spend our time powerfully shape the way we think and act. It is not the case that we can muster the ability to perform optimally no matter the setting—a truth that architects have long acknowledged, even as our larger society has dismissed it … Today, we too often learn and work in spaces that are far from being in harmony with our human nature, that in fact make intelligent and effective thinking ‘very difficult.’ Yet the built environment—when we know how to arrange it—can produce just the opposite effect: it can sharpen our focus; it can sustain our motivation; it can enhance our creativity and enrich our experience of daily life.”

- Allen curve: “People who work near one another are more likely to communicate and collaborate … The curve describes a consistent relationship between physical distance and frequency of communication: the rate of people’s interactions declines exponentially with the distance between the spaces where they work … People who are located close to one another are more likely to encounter one another, and it’s these encounters that spark informal exchanges, interdisciplinary ideas, and fruitful collaborations.”

- Owned, familiar space: “When people occupy spaces that they consider their own, they experience themselves as more confident and capable. They are more efficient and productive. They are more focused and less distractible. And they advance their own interests more forcefully and effectively … When we’re on our home turf, our mental and perceptual processes operate more efficiently, with less need for effortful self-control. The mind works better because it doesn’t do all the work on its own; it gets an assist from the structure embedded in its environment, structure that marshals useful information, supports effective habits and routines, and restrains unproductive impulses … With ownership comes control, and a sense of control over their space—how it looks and how it functions—leads people to perform more productively.”

- Ambient belonging: “Individuals’ sense of fit with a physical environment, along with a sense of fit with the people who are imagined to occupy that environment.”

- Most effective mental extension: “A private space, persistent and therefore familiar, over which they have a sense of ownership and control.”

Idea Spaces:

“The human brain is not well equipped to remember a mass of abstract information. But it is perfectly tuned to recalling details associated with places it knows—and by drawing on this natural mastery of physical space, we can more than double our effective memory capacity. Extending our minds via physical space can do more than improve our recall, however. Our powers of spatial cognition can help us to think and reason effectively, to achieve insight and solve problems, and to come up with creative ideas.”

- Spatial memory: “The difference between ‘superior memorizers’ and ordinary people lay in the parts of the brain that became active when the two groups engaged in the act of recall; in the memory champions’ brains, regions associated with spatial memory and navigation were highly engaged, while in ordinary people these areas were much less active.”

- Concept Mapping: “It forces us to reflect on what we know, and to organize it into a coherent structure. As we construct the concept map, the process may reveal gaps in our understanding of which we were previously unaware. And, having gone through the process of concept mapping, we remember the material better—because we have thought deeply about its meaning. Once the concept map is completed, the knowledge that usually resides inside the head is made visible.”

- Note-taking: “As with the creation of concept maps, the process of taking notes in the field, itself confers a cognitive bonus. When we simply watch or listen, we take it all in, imposing few distinctions on the stimuli streaming past our eyes and ears. As soon as we begin making notes, however, we are forced to discriminate, judge, and select. This more engaged mental activity leads us to process what we’re observing more deeply. It can also lead us to have new thoughts; our jottings build for us a series of ascending steps from which we can survey new vistas.”

- Models: “Across the board, in every field, experts are distinguished by their skillful use of externalization … Skilled artists, scientists, designers, and architects don’t limit themselves to the two-dimensional space of the page. They regularly reach for three-dimensional models, which offer additional advantages: users can manipulate the various elements of the model, view the model from multiple perspectives, and orient their own bodies to the model, bringing the full complement of their ’embodied resources’ to bear on thinking about the task and the challenges it presents.”

Thinking with Relationships

“The development of intelligent thinking is fundamentally a social process. We can engage in thinking on our own, of course, and at times solitary cognition is what’s called for by a particular problem or project. Even then, solo thinking is rooted in our lifelong experience of social interaction; linguists and cognitive scientists theorize that the constant patter we carry on in our heads is a kind of internalized conversation. Our brains evolved to think with people: to teach them, to argue with them, to exchange stories with them. Human thought is exquisitely sensitive to context, and one of the most powerful contexts of all is the presence of other people. As a consequence, when we think socially, we think differently—and often better—than when we think non-socially.”

Experts:

“Imitation appears to be behind our success as a species. Developmental psychologists are increasingly convinced that infants’ and children’s facility for imitation is what allows them to absorb so much, so quickly … Imitation is at the root of our social and cultural life; it is, quite literally, what makes us human.”

- Cognitive apprenticeship: “Four features of apprenticeship that could be adapted to the demands of knowledge work: modeling, or demonstrating the task while explaining it aloud; scaffolding, or structuring an opportunity for the learner to try the task herself; fading, or gradually withdrawing guidance as the learner becomes more proficient; and coaching, or helping the learner through difficulties along the way.”

- Imitation: “Often the most efficient and effective route to successful performance … By copying others, imitators allow other individuals to act as filters, efficiently sorting through available options … Imitators can draw from a wide variety of solutions instead of being tied to just one. They can choose precisely the strategy that is most effective in the current moment, making quick adjustments to changing conditions … Copiers can evade mistakes by steering clear of the errors made by others who went before them, while innovators have no such guide to potential pitfalls … Imitators are able to avoid being swayed by deception or secrecy: by working directly off of what others do, copiers get access to the best strategies in others’ repertoires … Imitators save time, effort, and resources that would otherwise be invested in originating their own solutions. Research shows that the imitator’s costs are typically 60 to 75 percent of those borne by the innovator—and yet it is the imitator who consistently captures the lion’s share of financial returns.”

- Correspondence problem: “Engaging in effective imitation is like being able to think with other people’s brains—like getting a direct download of others’ knowledge and experience. But contrary to its reputation as a lazy cop-out, imitating well is not easy. It rarely entails automatic or mindless duplication. Rather, it requires cracking a sophisticated code—solving what social scientists call the ‘correspondence problem,’ or the challenge of adapting an imitated solution to the particulars of a new situation. Tackling the correspondence problem involves breaking down an observed solution into its constituent parts, and then reassembling those parts in a different way; it demands a willingness to look past superficial features to the deeper reason why the original solution succeeded, and an ability to apply that underlying principle in a novel setting. It’s paradoxical but true: imitating well demands a considerable degree of creativity.”

Peers:

“Scientists have theorized that we humans developed our oversized brains in order to deal with the complexity of our own social groups. As a result of evolutionary pressures, each of us alive today possesses a specialized ‘social brain’ that is immensely powerful … Neuroscientific findings join a larger body of evidence generated by psychology and cognitive science, all pointing to a striking conclusion: we think best when we think socially.”

- Social interactions/memories: “Alter our physiological state in ways that enhance learning, generating a state of energized alertness that sharpens attention and reinforces memory … The brain stores social information differently than it stores information that is non-social. Social memories are encoded in a distinct region of the brain. What’s more, we remember social information more accurately, a phenomenon that psychologists call the ‘social encoding advantage.'”

- Teaching/Tutoring: “Humans learn best from other (live) humans. Perhaps more surprising, people learn from teaching other people—often more than the pupils themselves absorb … Engaging students in tutoring their peers has benefits for all involved, and especially for the ones doing the teaching. Why would the act of teaching produce learning—for the teacher? The answer is that teaching is a deeply social act, one that initiates a set of powerful cognitive, attentional, and motivational processes that have the effect of changing the way the teacher thinks.”

- Argument/Debate: “Research has consistently found that argument—when conducted in the right way—produces deeper learning, sounder decisions, and more innovative solutions … Engaging in active debate puts us in the position of evaluating others’ arguments, not simply constructing (and promoting) our own. Such objective analysis, unclouded by self-interested confirmation bias, makes the most of humans’ discriminating intelligence.”

- Storytelling: “Cognitive scientists refer to stories as ‘psychologically privileged,’ meaning they are granted special treatment by our brains. Compared to other informational formats, we attend to stories more closely. We understand them more readily. And we remember them more accurately. Research has found that we recall as much as 50 percent more information from stories than from expository passages … Why do stories exert these effects on us? One reason is that stories shape the way information is shared in cognitively congenial ways. The human brain has evolved to seek out evidence of causal relationships: this happened because of that. Stories are, by their nature, all about causal relationships; Event A leads to Event B, which in turn causes Event C, and so on.”

Groups:

“The limitations of excessive ‘cognitive individualism’ are becoming increasingly clear as well. Individual cognition is simply not sufficient to meet the challenges of a world in which information is so abundant, expertise is so specialized, and issues are so complex. In this milieu, a single mind laboring on its own is at a distinct disadvantage in solving problems or generating new ideas. Something beyond solo thinking is required—the generation of a state that is entirely natural to us as a species, and yet one that has come to seem quite strange and exotic: the group mind.”

- Behavioral/cognitive/neural synchrony & physiological arousal: “A substantial body of research shows that behavioral synchrony—coordinating our actions, including our physical movements, so that they are like the actions of others—primes us for what we might call cognitive synchrony: multiple people thinking together efficiently and effectively … Synchrony sends a tangible signal to others that we are open to cooperation, as well as capable of cooperation … Behavioral synchrony and shared physiological arousal in small groups independently increase social cohesion and cooperation … Both behavioral and physiological synchrony, in turn, generate greater cognitive synchrony … Emerging research even points to the existence of ‘neural synchrony’—the intriguing finding that when a group of individuals are thinking well together, their patterns of brain activity come to resemble one other’s. Though we may imagine ourselves as separate beings, our minds and bodies have many ways of bridging the gaps.”

- Shared attention & cognitive prioritization: “Occurs when we focus on the same objects or information at the same time as others. The awareness that we are focusing on a particular stimulus along with other people leads our brains to endow that stimulus with special significance, tagging it as especially important. We then allocate more mental bandwidth to that material, processing it more deeply; in scientists’ terms, we award it ‘cognitive prioritization’ … Shared attention, and the increased cognitive resources devoted to information that is mutually attended to, produces greater overlap in group members’ ‘mental models’ of a problem, and therefore smoother cooperation while solving it.”

- Entitativity/Groupiness: “Psychologists have found that groups differ widely on what they call ‘entitativity’—or, in a catchier formulation, their ‘groupiness.’ Some portion of the time and effort we devote to cultivating our individual talents could more productively be spent on forming teams that are genuinely groupy.”

- Transactive memory: “The process by which we leverage an awareness of the knowledge other people possess … The value of a transactive memory system lies in its members thinking different thoughts while also remaining aware of the contents of their fellow members’ minds.”

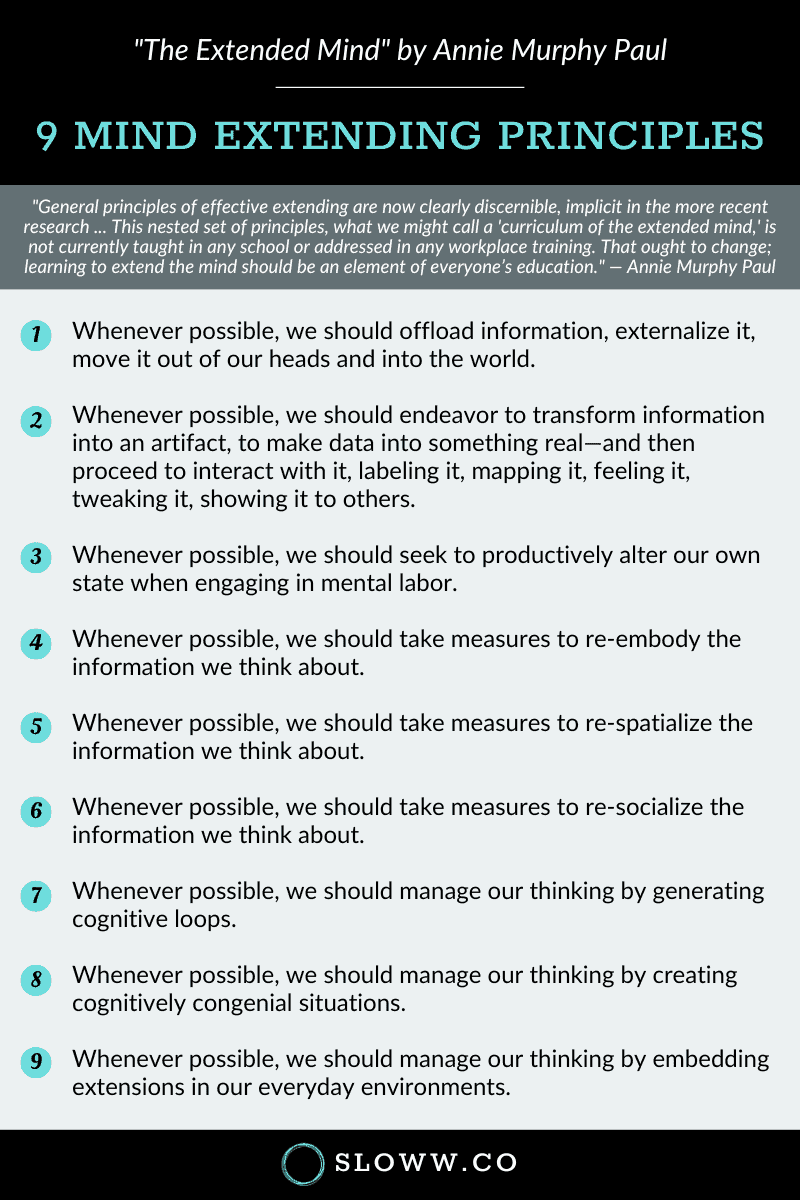

9 Mind Extending Principles

“General principles of effective extending are now clearly discernible, implicit in the more recent research … This nested set of principles, what we might call a ‘curriculum of the extended mind,’ is not currently taught in any school or addressed in any workplace training. That ought to change; learning to extend the mind should be an element of everyone’s education.”

Principle 1:

“Whenever possible, we should offload information, externalize it, move it out of our heads and into the world.”

- “It relieves us of the burden of keeping a host of details ‘in mind,’ thereby freeing up mental resources for more demanding tasks, like problem solving and idea generation … Externalizing information may entail carefully designing a task such that one part of the task is offloaded even as another part absorbs our full attention.”

- Offloading: “The simple act of putting our thoughts down on paper—simple, but often skipped over in a world that values doing things in our heads … A habit of continuous offloading—through the use of a daily journal or field notebook—can extend our ability to make fresh observations and synthesize new ideas … Offloading information onto a space that’s big enough for us to physically navigate (wall-sized outlines, oversized concept maps, multiple-monitor workstations) allows us to apply to that material our powers of spatial reasoning and spatial memory … Offloading may be embodied: when we gesture, for example, we permit our hands to ‘hold’ some of the thoughts we would otherwise have to maintain in our head. Likewise, when we use our hands to move objects around, we offload the task of visualizing new configurations onto the world itself, where those configurations take tangible shape before our eyes … … Offloading may be social: we’ve seen how engaging in argument allows us to distribute among human debaters the task of tallying points for and against a given proposition; we’ve learned how constructing a transactive memory system offloads onto our colleagues the task of monitoring and remembering incoming information … Offloading also occurs in an interpersonal context when we externalize ‘traces’ of our own thinking processes for the benefit of our teammates; in this case, we’re offloading not to unburden our own minds but to facilitate collaboration with others.”

Principle 2:

“Whenever possible, we should endeavor to transform information into an artifact, to make data into something real—and then proceed to interact with it, labeling it, mapping it, feeling it, tweaking it, showing it to others.”

- “Humans evolved to handle the concrete, not to contemplate the abstract. We extend our intelligence when we give our minds something to grab onto … Our days are now spent processing an endless stream of symbols; with a bit of ingenuity, we can find ways to turn these abstract symbols into tangible objects and sensory experiences, and thereby think about them in new ways.”

Principle 3:

“Whenever possible, we should seek to productively alter our own state when engaging in mental labor.”

- “The way we’re able to think about information is dramatically affected by the state we’re in when we encounter it … Effective mental extension requires us to think carefully about inducing in ourselves the state that is best suited for the task at hand … Instead of heedlessly driving the brain like a machine, we’ll think more intelligently when we treat it as the context-sensitive organ it is.”

Principle 4:

“Whenever possible, we should take measures to re-embody the information we think about.”

- “The pursuit of knowledge has frequently sought to disengage thinking from the body, to elevate ideas to a cerebral sphere separate from our grubby animal anatomy. Research on the extended mind counsels the opposite approach: we should be seeking to draw the body back into the thinking process. That may take the form of allowing our choices to be influenced by our interoceptive signals—a source of guidance we’ve often ignored in our focus on data-driven decisions. It might take the form of enacting, with bodily movements, the academic concepts that have become abstracted, detached from their origin in the physical world. Or it might take the form of attending to our own and others’ gestures, tuning back in to what was humanity’s first language, present long before speech. As we’ve seen from research on embodied cognition, at a deep level the brain still understands abstract concepts in terms of physical action, a fact reflected in the words we use (‘reaching for a goal,’ ‘running behind schedule’); we can assist the brain in its efforts by bringing the literal body back into the act of thinking.”

Principle 5:

“Whenever possible, we should take measures to re-spatialize the information we think about.”

- “Neuroscientific research indicates that our brains process and store information—even, or especially, abstract information—in the form of mental maps. We can work in concert with the brain’s natural spatial orientation by placing the information we encounter into expressly spatial formats: creating memory palaces, for example, or designing concept maps. In the realm of education research, experts now speak of ‘spatializing the curriculum’—that is, simultaneously drawing on and strengthening students’ spatial capacities by having them employ spatial language and gestures, engage in sketching and mapmaking, and learn to interpret and create charts, tables, and diagrams.”

Principle 6:

“Whenever possible, we should take measures to re-socialize the information we think about.”

- “The continual patter we carry on in our heads is in fact a kind of internalized conversation. Likewise, many of the written forms we encounter at school and at work—from exams and evaluations, to profiles and case studies, to essays and proposals—are really social exchanges (questions, stories, arguments) put on paper and addressed to some imagined listener or interlocutor. As we’ve seen, there are significant advantages to turning such interactions at a remove back into actual social encounters. Research we’ve reviewed demonstrates that the brain processes the ‘same’ information differently, and often more effectively, when other human beings are involved—whether we’re imitating them, debating them, exchanging stories with them, synchronizing and cooperating with them, teaching or being taught by them. We are inherently social creatures, and our thinking benefits from bringing other people into our train of thought.”

Principle 7:

“Whenever possible, we should manage our thinking by generating cognitive loops.”

- “Something about our biological intelligence benefits from being rotated in and out of internal and external modes of cognition, from being passed among brain, body, and world. This means we should resist the urge to shunt our thinking along the linear path appropriate to a computer—input, output, done—and instead allow it to take a more winding route. We can pass our thoughts through the portal of our bodies: seeking the verdict of our interoception, seeing what our gestures have to show us, acting out our ideas in movement, observing the inspirations that arise during or after vigorous exercise. We can spread out our thoughts in space, treating the contents of the mind as a territory to be mapped and navigated, surveyed and explored. And we can run our thoughts through the brains of the people we know, gathering from the lot of them the insights no single mind could generate. Most felicitous of all, we can loop our thoughts through all three of these realms.”

Principle 8:

“Whenever possible, we should manage our thinking by creating cognitively congenial situations.”

- “We’ll elicit improved performance from the brain when we approach it with the aim not of issuing orders but of creating situations that draw out the desired result … The art of creating intelligence-extending situations is one that every parent, teacher, and manager needs to master.”

Principle 9:

“Whenever possible, we should manage our thinking by embedding extensions in our everyday environments.”

- “Once securely embedded, such extensions can function as seamless adjuncts to our neural capacity, supporting and augmenting our ability to think intelligently … In a dynamic and fast-changing society that celebrates novelty and flexibility, the maintenance and preservation of valued mental extensions also deserve our respect. We may not know how much they bolster our intelligence until they’re gone.”

You May Also Enjoy: