“If you say that money is the most important thing, you will spend your life completely wasting your time. You’ll be doing things you don’t like doing in order to go on living, that is, to go on doing things you don’t like doing.” — Alan Watts

Money money money. Whether you spend a bunch or save it all, it’s a topic we all have to deal with in some way.

If you Google something along the lines of “how much money is enough,” you’ll find a bunch of articles about total net worth, financial independence, and early retirement.

You’ll also see the vague answer, “It’s up to each individual person to decide how much is enough.” While that’s subjectively true, what does research say about enough money?

In the previous post, we looked at the data on average American annual expenses. But, what about annual income?

As you’ll see based on the research, money can actually buy happiness and well-being—to a point. Where do diminishing returns and turning points occur? What is enough, and can there ever be too much?

That word ‘enough’ is a relative term. We all should have our own set of unique life goals to guide financial decisions. Unfortunately, if you haven’t taken the time to explore your financial plans, you may end up getting trapped in the pursuit of more rather than the contentment of enough. — Forbes¹

How Much Income is Enough Money for Well-Being (According to Research)?

“If you worship money and things — if they are where you tap real meaning in life — then you will never have enough. Never feel you have enough…On one level, we all know this stuff already…The trick is keeping the truth up-front in daily consciousness.” ― David Foster Wallace

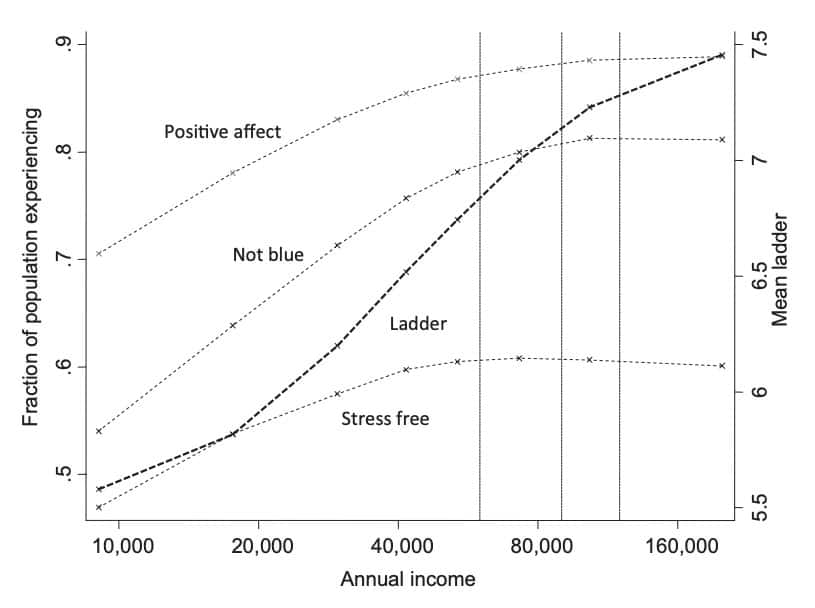

Let’s start with the primary piece of research on this topic: High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being² by Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton (published in 2010).

Kahneman and Deaton studied the impact of income on subjective well-being. Here are definitions for the two key things they investigated, emotional well-being and life evaluation:

- “Emotional well-being (sometimes called hedonic well-being or experienced happiness) refers to the emotional quality of an individual’s everyday experience—the frequency and intensity of experiences of joy, fascination, anxiety, sadness, anger, and affection that make one’s life pleasant or unpleasant.”

- “Life evaluation refers to the thoughts that people have about their life when they think about it.”

In Kahneman and Deaton’s own words:

- “We conclude that high income buys life satisfaction but not happiness, and that low income is associated both with low life evaluation and low emotional well-being.”

- “We infer that beyond about $75,000/year, there is no improvement whatever in any of the three measures of emotional well-being. In contrast, the figure shows a fairly steady rise in life evaluation with log income over the entire range.”

80000Hours.org, a career-planning resource, created a prettier graph than the one in the original research:

80000Hours.org has some of the most comprehensive summaries of all the available research on money and well-being. They break down the research further:

- “You can see that going from a (pre-tax) income of $40,000 to $80,000 is only associated with an increase in life satisfaction from about 6.5 to 7 out of 10. That’s a lot of extra income for a small increase.” — 80000Hours.org³

- “If we look at day-to-day happiness, income is even less important. ‘Positive affect’ is whether people reported feeling happy yesterday. The left shows the fraction of people who said ‘yes’. This line goes flat around $50,000, showing that beyond this point income had no relationship with day-to-day happiness.” — 80000Hours.org³

- “The other three lines start to flatten around $50,000, and are completely flat by $75,000 (household income). This means that extra income had no relationship with how happy, sad and stressed people felt after this point.” — 80000Hours.org4

The Latest Income Research Studying How Much Money is Enough

“Your freedom is more important than money. It is better to live the kind of life you want than to earn more and be constrained. Don’t sell your freedom.” — Haemin Sunim

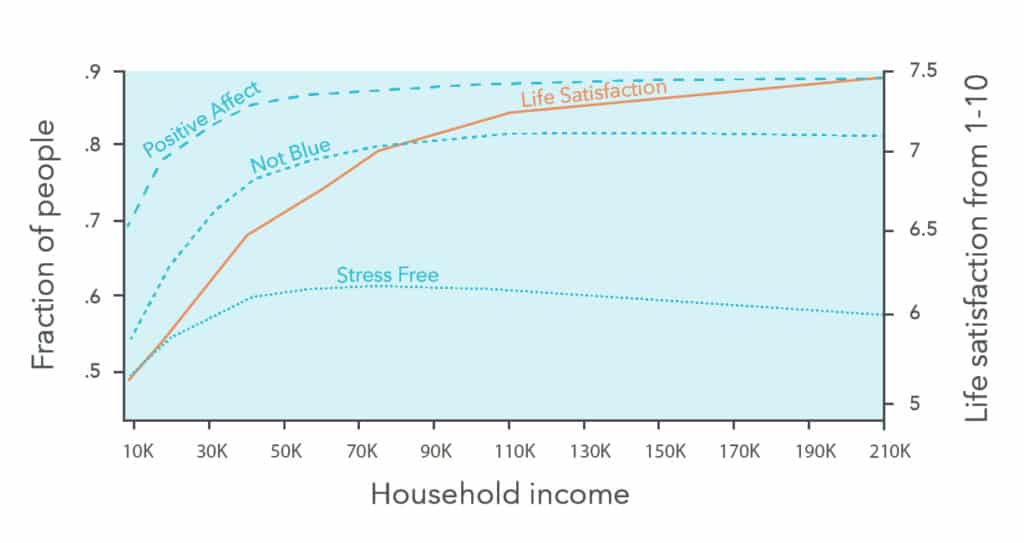

It’s hard to believe that 2010 was almost a decade ago. Lucky for us, some more recent research was published in 2018: Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the world5 by Andrew T. Jebb, Louis Tay, Ed Diener, and Shigehiro Oishi.

Recall in the 2010 study above that there was no diminishing return for life evaluation and a $75,000 point for subjective well-being. Interestingly, the 2018 research concluded lower amounts needed for each of these:

Why were their results lower?

- “How do our findings relate to previous studies on satiation? The most prominent satiation study to date estimated satiation for affective well-being in the U.S. at $75,000 but did not find it for life evaluation (other studies have yielded similar results for life evaluation). Our findings in the Northern American sample, comprised of Canada and the U.S., are slightly lower than their results for affective measures ($65,000 for positive affect, $95,000 for negative affect) and can be explained by our use of equivalized household income. We also found a clear satiation effect at $105,000 for life evaluation. This difference can again be explained by our use of equivalized income and other differences in data and method.”

- “The estimates here pertain to single-person households only. To obtain estimates for households with more people, one can simply multiply the satiation estimate by the square root of the household size. For instance, a household with four members would have a satiation point two times higher than the estimates reported here.”

Here’s what those income satiation points look like when you slice and dice the data in different ways:

This research even goes a step further to suggest that too much money can actually negatively impact happiness at certain “turning points”:

- “They also found ‘turning points’ in certain parts of the world, where if people made more money past the point of satiation, their life evaluations actually got worse. However, the Purdue and Virginia researchers suggest that the costs associated with higher incomes such as higher demands on time, heavier workloads and greater responsibility may be driving these reductions, rather than the high incomes themselves.” — Gallup6

- “Theoretically, it is presumably not the higher incomes themselves that drive reductions in SWB (subjective well-being) but the costs associated with them. High incomes are usually accompanied by high demands (time, workload, responsibility, etc.) that might also limit opportunities for positive experiences (e.g., leisure activities). Additional factors may play a role as well, such as an increase in materialistic values, additional material aspirations that may go unfulfilled, increased social comparisons or other life changes in reaction to greater income (e.g., more children, living in more expensive neighborhoods). Importantly, the ill effects of the highest incomes may not just be present when one’s maximum income is finally reached but could also occur in the process of its attainment.”5

Getting Started with Enough

“He who knows he has enough is rich.” — Lao Tzu

First, let’s establish that there’s a difference between voluntary simplicity (deciding you have enough) and poverty (not having enough):

Poverty is involuntary and debilitating, whereas simplicity is voluntary and enabling. Poverty is mean and degrading to the human spirit, whereas a life of conscious simplicity can have both a beauty and a functional integrity that elevates the human spirit. Involuntary poverty generates a sense of helplessness, passivity, and despair, whereas purposeful simplicity fosters a sense of personal empowerment, creative engagement, and opportunity. — Duane Elgin

Also, all increases in income are not created equally:

The difference between earning $20,000 and $40,000 is huge and life-changing. The difference between earning $120,000 and $140,000 means your car has slightly nicer seat heaters. The difference between earning $127,020,000 and $127,040,000 is basically a rounding error on your tax return. — Mark Manson

The research presented in this post shows that we are all subject to certain universal laws of well-being. There are minimums and maximums when it comes to making money. The goal is to figure out what is enough for you.

You can take some inspiration from those in the FIRE community (Financial Independence Retire Early) who often have household annual spending in the $25-40,000/year range. This is well under the average annual American household spending of $60,060 in 2017.

Other individual sources of inspiration are leading philosophers Will MacAskill and Toby Ord:

- Will MacAskill (31 years old) has pledged to donate everything he earns over ~$36,000/year to effective charities.

- Toby Ord (39 years old) realized that with the money he was going to make over his lifetime, he could cure 80,000 people of blindness in developing countries and still have enough left to live a perfectly adequate life.7

I’ll leave you with a quote and video from Vicki Robin, author of the bestselling book Your Money or Your Life: 9 Steps to Transforming Your Relationship with Money and Achieving Financial Independence. Vicki Robin was called “the prophet of consumption down-sizers” by the New York Times and had this to say about enough:

The new roadmap says that there is something called ‘enough’…’enough’ is this vibrant, vital place…an awareness about the flow of money and stuff in your life, in light of your true happiness and your sense of purpose and values, and that your ‘enough point’ (having enough) is having everything you want and need, to have a life you love and full self-expression, with nothing in excess. It’s not minimalism. It’s not less is more (because sometimes more is more), but it’s that sweet spot, it’s the Goldilocks point. Enough for me is one of the absolute fulcrums between the old roadmap for money and the new roadmap for money…Once people start to pay attention to the flow of money and stuff in their lives in this way, their consumption drops by about 20-25% naturally because that’s the amount of unconsciousness that you have in your spending. So, when you become conscious, that falls away and many people say they don’t even know what they used to spend their money on. — Vicki Robin

See the full video of Vicki Robin here:

Have you determined the “enough point” in your life yet? If so, please let me know in the comments!

Sources:

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/financialfinesse/2017/11/20/how-much-money-is-really-enough/#596fc02b6618

- https://www.princeton.edu/~deaton/downloads/deaton_kahneman_high_income_improves_evaluation_August2010.pdf

- https://80000hours.org/career-guide/job-satisfaction/

- https://80000hours.org/articles/money-and-happiness/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321743107_Happiness_Income_Satiation_and_Turning_Points_Around_the_World

- https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/228278/rich-hurt-chances-happiness.aspx

- https://blog.ted.com/effective-altruism-peter-singer-at-ted2013/