This is a book summary of Interdisciplinary Research: Process and Theory by Allen Repko and Rick Szostak (Amazon).

🔒 Premium members get access to the companion synthesis: Interdisciplinary Synthesis: How to be an Interdisciplinarian (+ Infographics)

Quick Housekeeping:

- This book builds on a prior one: “Introduction to Interdisciplinary Studies” (Book Summary)

- All content in quotation marks is from the authors (otherwise it’s minimally paraphrased).

- All content is organized into my own themes (not necessarily the authors’ chapters).

- Emphasis has been added in bold for readability/skimmability.

Book Summary Contents:

- About the Book

- Disciplines & Interdisciplinarity

- Common Ground

- Integration & Understanding

- 10 STEPS of the IRP (+ Infographic)

Process & Theory: Interdisciplinary Research by Repko & Szostak (Book Summary)

About the Book

“Interdisciplinary studies uses a research process designed to produce new knowledge in the form of more comprehensive understandings of complex problems. The focus of this book is on this research process … The book presents an integrated model of the interdisciplinary research process.”

With repeated exposure to interdisciplinary thought, students develop:

- more mature epistemological beliefs.

- enhanced critical thinking ability.

- metacognitive skills.

- an understanding of the relations among perspectives derived from different disciplines.

This book’s approach to interdisciplinary research is distinctive in at least six respects:

- “It describes how to actually do interdisciplinary research using processes and techniques of demonstrated utility whether one is working in the natural sciences, the social sciences, the humanities, or applied fields.”

- “It integrates and applies the body of theory that informs the field into the discussion of the interdisciplinary research process.”

- “It presents an easy-to-follow, but not formulaic, decision-making process that makes integration and the goal of producing a more comprehensive understanding achievable. The term process is used rather than method because, definitionally, process allows for greater flexibility and reflexivity, particularly when working in the humanities, and it distinguishes interdisciplinary research from disciplinary methods.”

- “The book highlights the foundational and complementary role of the disciplines in interdisciplinary work, the necessity of drawing on and integrating disciplinary insights, including insights derived from one’s own basic research.”

- “The book includes numerous examples of interdisciplinary work from the natural sciences, the social sciences, and the humanities to illustrate how integration is achieved and how an interdisciplinary understanding is constructed, reflected on, tested, and communicated.”

- “This book is ideally suited for active learning and problem-based pedagogical approaches, as well as for team teaching and other more traditional strategies.”

Disciplines & Interdisciplinarity

“The premise of interdisciplinary studies is that the disciplines themselves are the necessary preconditions for and foundation of interdisciplinarity.”

The role of disciplines:

“Disciplinary means ‘of or relating to a particular field of study’ or specialization … Disciplines are scholarly communities that specify which phenomena to study, advance certain central concepts and organizing theories, embrace certain methods of investigation, provide forums for sharing research and insights, and offer career paths for scholars.”

- Disciplines are means: “The important point is that the disciplines are not the focus of the interdisciplinarian’s attention; the focus is the problem or issue or intellectual question that each discipline is addressing. The disciplines are simply a means to that end.”

- Disciplinary perspective: “A discipline’s view of reality in a general sense that embraces and in turn reflects the ensemble of its defining elements that include phenomena, epistemology, assumptions, concepts, theories, and methods.”

- Multidisciplinary: “Merely examining a behavior or object from different disciplinary perspectives does not by itself constitute interdisciplinary work. Without integration, these different perspectives would lead to mere multidisciplinary work … The interdisciplinary mind tends to go beyond mere appreciation of other disciplinary perspectives (i.e., multidisciplinarity); it evaluates their capacity to address a problem and assesses their relevance.”

- Perspective taking: “In interdisciplinary work, perspective taking involves appreciating alternative disciplinary perspectives. This does not mean abandoning one’s own disciplinary beliefs to the views of another discipline. It does mean being aware of more than one way to account for natural and social phenomena and processes.”

- Depth & breadth: “The disciplines provide the depth while interdisciplinarity provides the breadth and the integration … Interdisciplinary integration is only possible because of the concerted efforts of thousands of scholars across all disciplines. Their insights provide both the disciplinary depth and the disciplinary breadth that makes interdisciplinary integration possible.”

- Symbiotic: “There should be a symbiotic relationship between interdisciplinary research and disciplinary or specialized research … Interdisciplinary insights resulting from integration can feed back into disciplinary research; encourage new questions; change concepts, theories, and methods; and encourage interdisciplinary researchers to pay attention to a wider range of phenomena.”

All about interdisciplinarity:

“The prefix inter- means ‘between, among, in the midst,’ or ‘derived from two or more’ … A starting point for understanding the meaning of interdisciplinary studies is between two or more fields of study … Interdisciplinary studies is a process of answering a question, solving a problem, or addressing a topic that is too broad or complex to be dealt with adequately by a single discipline, and draws on the disciplines with the goal of integrating their insights to construct a more comprehensive understanding.”

Interdisciplinarity & interdisciplinary studies/research:

- an emerging paradigm of knowledge formation whose spreading influence can no longer be denied, discounted, or ignored (asking research questions that do not unnecessarily constrain theories, methods, or phenomena; drawing upon diverse theories and methods; drawing connections among diverse phenomena; evaluating the insights of scholars from different disciplines in the context of disciplinary perspective).

- about building bridges that join together, creating commonalities, inclusion, and producing understandings/meanings that are new/more comprehensive (rather than building walls that divide, sharpening differences, exclusion, or using a single disciplinary approach).

- has a research process of its own to produce knowledge (interdisciplinary research is a process where the necessarily incomplete research of one scholar is built upon by others because no research is ever completely comprehensive; freely borrows methods from the disciplines when appropriate).

- seeks to produce new knowledge via the process of integration (draws on existing disciplinary knowledge while always transcending it via integration; seeks to integrate insights from multiple disciplines after evaluating these in the context of disciplinary perspective; integrating the insights of disciplinary scholars in order to achieve a holistic understanding).

- has the goal of achieving the most comprehensive understanding of the problem possible (produces a cognitive advancement in the form of a new understanding, a new product, or a new meaning; associated with bold advances in knowledge, solutions to urgent societal problems, an edge in technological innovation, and a more integrative educational experience; concerned with achieving an interdisciplinary understanding of the problem as a whole; the understanding cannot be truly comprehensive if it excludes certain views or is dominated by certain views; if the scales of scholarship are prejudiced, then the rigor, comprehensiveness, and intellectual integrity of the project will be seriously, or even fatally, compromised).

Interdisciplinarians:

- are self-consciously interdisciplinary (reflecting on your biases (disciplinary and personal), serving as an honest broker when confronting conflicting viewpoints, and all the while keeping in view the end product that prompted the research in the first place).

- bring a toolkit of cognitive abilities and skills (along with a process to achieve integration, and techniques to construct a more comprehensive solution to complex problems).

- approach a problem with a frame of mind that is decidedly different from that of the disciplinarian (one of neutrality, or at least suspended judgment, and objectivity until all the evidence is in).

- read widely to make novel discoveries (better to err on the side of inclusiveness than to conclude prematurely that a discipline is not relevant).

- look for what disciplinarians have failed to see (start broadly and narrow the focus towards more specialized sources as the topic takes shape).

- have an openness to different disciplinary insights and theories (even if these challenge deeply held beliefs).

- need to maintain some psychological distance from the disciplinary perspectives on which they draw (borrowing from them without completely buying into them).

- produce an understanding of a problem that is more comprehensive/inclusive (than the narrow/skewed understandings that the disciplines have produced).

Common Ground

“Common ground theory says that ‘every act of communication presumes a common cognitive frame of reference between the partners of interaction called the common ground’ … Common ground is the shared basis that exists between conflicting disciplinary insights or theories and makes integration possible.”

Creating common ground:

“A defining characteristic of interdisciplinary work should be to mitigate conflict by finding common ground among conflicting perspectives, including your own … Common ground is something that the interdisciplinarian must create or discover … One occasion when creating common ground is required is when people (or disciplines) use different concepts or terms to describe the same thing.”

- “Creating or discovering common ground involves modifying or reinterpreting disciplinary elements (i.e., concepts, assumptions, or theories) that conflict.”

- “Interdisciplinarians are interested in concepts because when they are modified, they can often serve as the basis for creating common ground and integrating insights.”

- “Unless you have consciously gathered enough relevant information, you will not be able to subconsciously develop common ground.”

- “In interdisciplinary communication, common ground is frequently ‘discovered’ when the partners of cooperation—that is, the relevant disciplines—’find out that they use the same concepts with different meanings, or that they use different terms for approximately the same concepts.'”

- “This process calls for interdisciplinarians, whether they are developing a collaborative language or trying to integrate conflicting disciplinary insights, to first identify the concepts with different meanings or the theories providing different explanations before attempting to discover common ground. Once these are identified, the interdisciplinarian can then proceed with creating the ‘common ground integrator’—that is, the concept, assumption, or theory—by which these conflicting insights (whether disciplinary or stakeholder) can be integrated.”

Common ground techniques:

“The value of these techniques is that they enable us to create common ground when working with concepts (and their underlying assumptions). They replace the either/or thinking characteristic of the disciplines with both/and thinking characteristic of interdisciplinary integration. Inclusion, insofar as this is possible, is substituted for conflict.”

- Redefinition (or ‘textual integration’): “Modifying or redefining concepts in different texts and contexts to bring out a common meaning. The focus of redefinition is linguistic.”

- Extension: “Increasing the scope of the ‘something’ that we are talking about. The focus of extension is conceptual. It involves addressing differences or oppositions in disciplinary concepts and/or assumptions by extending their meaning beyond the domain of the discipline that originated them into the domain(s) of the other relevant discipline(s). Extending into the domain of a different discipline almost inevitably involves some sort of modification.”

- Transformation: “Used to modify concepts or assumptions that are not merely different (e.g., love, fear, selfishness) but opposite (e.g., rational, irrational) into continuous variables … The value of transformation in creating common ground is this: Rather than force us to accept or reject dichotomous concepts and assumptions, continuous variables allow us to integrate opposing insights. The effect of this strategy is not only to resolve a philosophical dispute, but also to extend the range of a theory. Transforming opposing assumptions into variables allows the interdisciplinarian to move toward resolving almost any dichotomy or duality.”

- Organization: “Clarifying how certain phenomena interact and mapping their causal relationships. More specifically, organization: (1) identifies a latent commonality in the meaning of different concepts or assumptions (or variables) and redefines them accordingly, and (2) then organizes, arranges, arrays, or maps the redefined concepts or assumptions to bring out a relationship between them.”

Integration & Understanding

“The English word integration can be traced back to the Latin word integrare, meaning ‘to make whole.’ As a verb, integrate means ‘to unite or blend into a functioning whole.’ Over the centuries, says Klein, ‘the idea of integration was associated with holism, unity, and synthesis.'”

Interdisciplinary integration:

“Integration is the cognitive process of critically evaluating disciplinary insights and creating common ground among them to construct a more comprehensive understanding. The new understanding is the product or result of the integrative process.”

- Process (not activity): “Process conveys the notion of making gradual changes that lead toward a particular (but often unanticipated) result, whereas activity has the more limited meaning of vigorous or energetic action not necessarily related to achieving a goal.”

- Raw material: “Theories and the insights they produce along with their concepts and assumptions constitute the ‘raw material’ used in integration.”

- Synthesis: “Integration is the means by which the end or goal of the research process is achieved. Klein (1996) states, ‘Synthesis connotes creation of an interdisciplinary outcome through a series of integrative actions’ … A synonym of integration is the noun synthesis. Because the terms integration and synthesis are so close in meaning, many practitioners use them interchangeably.”

- Integrative wisdom: “The synthetic interaction between ‘inspiration, intellect, and intuition.’ Wisdom is the synthesis of all avenues of insight—rational, experiential, intuitive, physical, cultural, and emotional. (It) breaks down all boundaries between categories of knowledge and returns them (to) holistic understanding. Wisdom creates equilibrium among these faculties, minimizing their individual weaknesses and achieving synergy.”

Generalists vs Integrationists:

- Generalists: Reject the notion that integration should be the defining feature of genuine interdisciplinary research and teaching; understand interdisciplinarity loosely to mean ‘any form of dialog or interaction between two or more disciplines,’ while minimizing, obscuring, or rejecting altogether the role of integration.

- Integrationists: Regard integration as the key distinguishing characteristic of interdisciplinarity and the goal of fully interdisciplinary work; researchers should come as close to achieving integration as possible given the problem under study and the disciplinary insights at their disposal.

Successfully performing integration and engaging in perspective taking require that you consciously cultivate these qualities of mind:

- Thinking inclusively and integratively, not exclusively.

- Being responsive to each perspective but dominated by none (i.e., not allowing one’s strength in a particular discipline to influence one’s treatment of other relevant disciplines with which one is less familiar).

- Maintaining intellectual flexibility.

- Thinking both inductively and deductively.

- Thinking about the whole while simultaneously working with parts.

More comprehensive understanding:

“The integration of concepts, assumptions, or theories is a means to the end of integrating insights into a more comprehensive understanding … Practitioners refer to the result of the integrative process as culminating in a new and more comprehensive understanding. This understanding is sometimes called ‘the integrative result,’ ‘the new whole,’ ‘the new meaning,’ ‘the integrative product,’ ‘the extended theoretical explanation,’ ‘the conceptual blend,’ ‘the cognitive advancement,’ ‘complex understanding,’ ‘holistic understanding,’ ‘interdisciplinary understanding,’ ‘integrative understanding,’ ‘integrated result,’ and/or ‘interdisciplinary product.’“

- “The result of the integration of insights involves a new and more complete and perhaps more nuanced understanding than any of the disciplinary insights could produce.”

- ‘More comprehensive’: Refers to the defining characteristic of the understanding or theory: that it combines more elements than does any disciplinary understanding or theory.

- ‘Understanding’: Reminds us that the purpose of integration is to better comprehend a particular issue, problem, or question; this will often allow us to better address real-world challenges.

- ‘Integration’: Refers to the process used to construct the understanding or theory.

- ‘Insights’: Get integrated, not the contributing disciplines themselves or their perspectives.

- ‘New’: References the improbability of any one discipline producing a similar result, and that no one (other than the interdisciplinarian) takes responsibility for studying the complex problem, object, text, or system that transcends the disciplines.

- ‘More complete’: Refers to the understanding or theory that includes more aspects, facets, or dimensions than does a disciplinary understanding.

- ‘Nuanced’: Refers to the understanding or theory that includes more subtle distinctions than do disciplinary understandings.

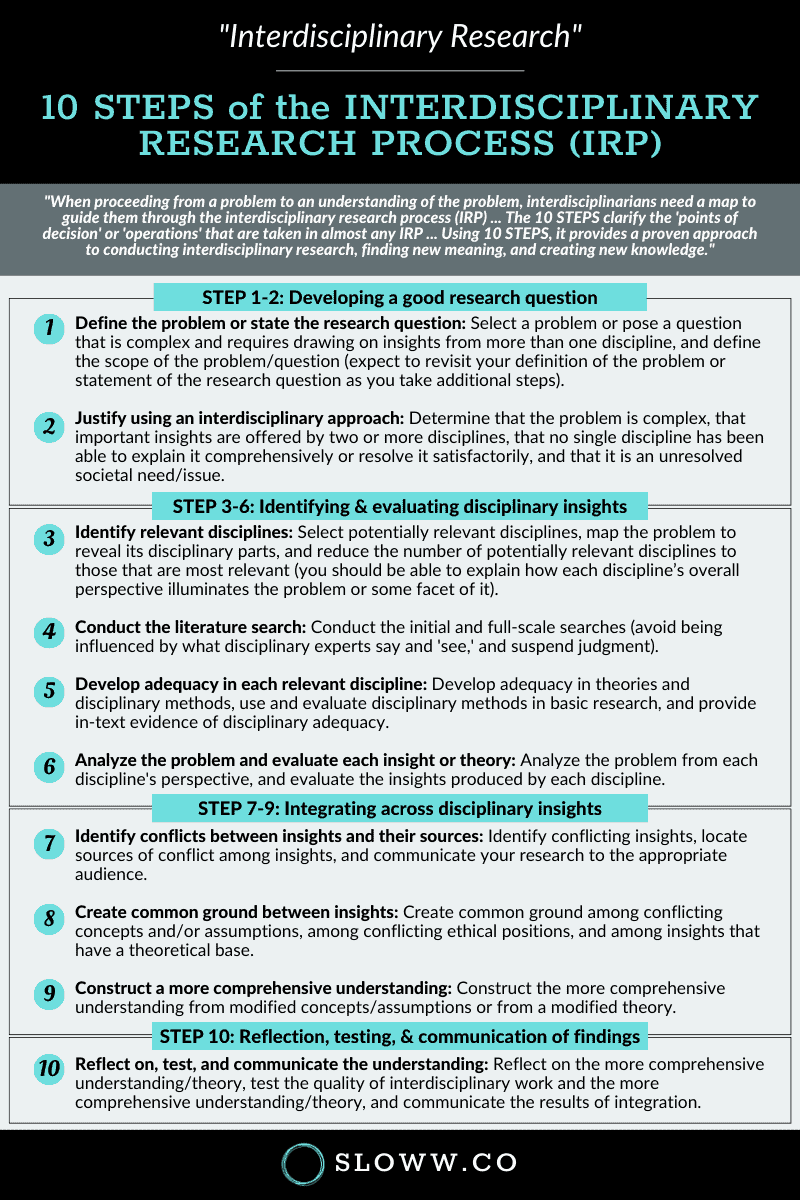

10 STEPS of the Interdisciplinary Research Process (IRP)

Overview of the STEPS:

“When proceeding from a problem to an understanding of the problem, interdisciplinarians need a map to guide them through the interdisciplinary research process or IRP … The 10 STEPS clarify the ‘points of decision’ or ‘operations’ that are taken in almost any interdisciplinary research project … Using 10 STEPS, it provides a proven approach to conducting interdisciplinary research, finding new meaning, and creating new knowledge.”

- STEP 1-2: developing a good research question.

- STEP 3-6: identifying and evaluating disciplinary insights.

- STEP 7-9: integrating across disciplinary insights.

- STEP 10: reflection, testing, and communication of findings.

STEP 1. Define the problem or state the research question:

· Select a problem or pose a question that is complex and requires drawing on insights from more than one discipline.

· Define the scope of the problem or question.

· Avoid three tendencies that run counter to the IRP.

· Follow three guidelines for stating the problem or posting the question.

Select a problem or pose a question that is complex and requires drawing on insights from more than one discipline:

- Definition: “A problem is ripe for interdisciplinary study when it is complex (i.e., requires insights from more than one discipline), and it is researchable in an interdisciplinary sense (i.e., authors from at least two disciplines have written on the topic or at least on some aspect of it).”

- Prepared mind: “Good ideas only come to the prepared mind: You need consciously to think and read about an area of interest before you can subconsciously develop a good research question.”

- Burning question: “Some students may begin with some burning question that has long troubled them, and find that it is suitable for interdisciplinary inquiry … You are more likely to develop a good question if you care about the topic in which you are reading.”

Define the scope of the problem or question:

- Definition: “Scope refers to the parameters of what you intend to include and exclude from consideration … The extremes to be avoided are conceiving the problem too broadly so that it is unmanageable, and conceiving the problem too narrowly so that it is not interdisciplinary or researchable.”

Avoid three tendencies that run counter to the IRP:

- Disciplinary bias: To state the problem using words and phrases that connect it to a particular discipline.

- Disciplinary jargon: Using technical terms and concepts that are not generally understood outside a particular discipline.

- Personal bias: One’s own point of view when introducing the problem; injecting your personal bias is not appropriate in most interdisciplinary contexts where the goal is quite different: to construct a more comprehensive understanding.

Follow three guidelines for stating the problem or posting the question:

- Clear/concise: Problem should be stated clearly and concisely.

- Narrow/manageable: Problem or focus question should be sufficiently narrow in scope to be manageable (depending on the scale of the writer’s project).

- Context/importance: Problem should appear in a context (preferably in the first paragraph of the introduction) that explains why it is important (why the reader should care).

Keep in mind:

“As further STEPS are taken, you are likely to encounter new information, receive new insights (including flashes of intuition), or encounter unforeseen problems that will require revisiting the initial STEP and modifying the research question. This is a normal part of the interdisciplinary research process … You should expect to revisit your definition of the problem or statement of the research question as you take additional steps.”

STEP 2. Justify using an interdisciplinary approach:

· Determine that the problem is complex.

· Determine that important insights concerning the problem are offered by two or more disciplines.

· Determine that no single discipline has been able to explain the problem comprehensively or resolve it satisfactorily.

· Determine that the problem is an unresolved societal need or issue.

Determine that the problem is complex:

- Definition: “The operational definition of complexity used in this book is that the problem has multiple parts studied by different disciplines.”

Determine that important insights concerning the problem are offered by two or more disciplines:

- Researchability: “A problem that is controversial has likely generated interest from two or more disciplines, each offering its own insights or theories in the form of books and journal articles. This condition makes the problem researchable.”

Determine that no single discipline has been able to explain the problem comprehensively or resolve it satisfactorily:

- Comprehensive approach: “The value of an interdisciplinary approach over a single disciplinary approach is that it can address complex problems in a more comprehensive way.”

Determine that the problem is an unresolved societal need or issue:

- Problem-based research: “Societal/public policy problems necessitate what is widely referred to as problem-based research, which focuses on unresolved societal needs, practical problem solving, and intellectual problems that are the focus of the humanities, such as the meaning of some artifact. What distinguishes problem-based research from other applied research is its holistic focus that involves more than one discipline.”

STEP 3. Identify relevant disciplines:

· Select potentially relevant disciplines.

· Map the problem to reveal its disciplinary parts.

· Reduce the number of potentially relevant disciplines to those that are most relevant.

Select potentially relevant disciplines:

- Definition: “A potentially relevant discipline is one whose research domain includes at least one phenomenon involved in the problem or research question … Ask this of each disciplinary perspective: ‘Does it illuminate some aspect of the problem, topic, or question?'”

Map the problem to reveal its disciplinary parts:

- Systems thinking/skills: “After selecting the disciplines potentially relevant to the research question, you need to identify the constituent parts of the problem, understand how these relate to each other and to the problem as a whole, and view the problem as a system … Using systems thinking and system mapping promotes: perspective taking (involves examining a problem from the standpoint of the interested disciplines and identifying the differences between them), nonlinear thinking (looking for nonlinear relationships among the phenomena or actors in a system), holistic thinking (view system parts in relationship to the system as a whole), and critical thinking (examine assumptions and base conclusions on evidence).”

Reduce the number of potentially relevant disciplines to those that are most relevant:

- 3-4 disciplines: “The most relevant disciplines are those disciplines, often three or four, that are most directly connected to the problem, have produced the most important research on it, and have advanced the most compelling theories to explain it.”

Keep in mind:

“At this early phase of the research process, you should be able to explain how each discipline’s overall perspective illuminates the problem or some facet of it.”

STEP 4. Conduct the literature search:

· Understand the meaning of the literature search.

· Appreciate the reasons for conducting the literature search.

· Special challenges confronting interdisciplinarians.

· The initial literature search.

· The full-scale literature search.

Understand the meaning of the literature search:

- Definition: “The process of gathering scholarly information on a given topic is the domain of the literature search, although the term commonly used in the natural and the social sciences is literature review … This search carefully examines previous research in journals, books, and conference papers to see how other researchers have addressed the problem … The literature search also serves to demonstrate adequacy in the disciplinary literature on the problem, how the current project is connected to prior research, and to summarize what is known about the problem.”

Appreciate the reasons for conducting the literature search:

- Literature search reasons: “To save time and effort; To discover what scholarly knowledge has been produced on the topic by different disciplines; To narrow the topic and sharpen the focus of the research question; To explain how the problem developed over time; To identify prior disciplinary research and understand how the proposed interdisciplinary project may extend our understanding of the problem; To situate or contextualize the problem; To develop ‘adequacy’ in the relevant disciplines (STEP 5); To verify that the disciplines identified at the end of STEP 3 as most interested in the problem are really relevant.”

Special challenges confronting interdisciplinarians:

- Suspend judgment: “Throughout the search process, (1) avoid being influenced by what disciplinary experts say and ‘see,’ and (2) suspend judgment about the problem … The nature of interdisciplinary work is to suspend judgment and patiently go through the process, letting the process reveal if one’s earlier assumption is in fact accurate … Students unfamiliar with interdisciplinarity and the research process risk becoming seduced by the existing literature. This seduction may lead to being overly impressed by a particular writer’s approach before first developing a clear understanding of how the problem should be approached in an interdisciplinary way.”

The initial literature search:

- Strategies/objective: “Strategies to conduct the initial phase of the literature search include browsing, probing, skimming, evaluating, and deciding … The point of the initial literature search is to decide whether there is enough information on the problem to make it researchable in an interdisciplinary sense. Once you have reached your decision, note that it may not be final until you have conducted the full-scale search and read the relevant disciplinary insights closely.”

The full-scale literature search:

- Inclusiveness: “Researchers at any level should always err on the side of inclusiveness during the full-scale search. Insights that are only marginally relevant will be identified later on and then discarded. But inclusive does not mean ‘open-ended.’ Inclusive refers not to the quantity of disciplinary insights but to their quality and diversity … Conducting the full-scale literature search requires closely reading insights from multiple disciplinary literatures for specific content, as well as organizing this information … It is best to use the author’s own words to eliminate the possibility of skewing the writer’s meaning, which may occur when paraphrasing.”

Keep in mind:

“It is good to consider STEP 4 as a fluid process within the overall research process, especially in its early phases … Basic to any research effort is the systematic gathering of information about the problem: the literature search. The IRP places the literature search at STEP 4. However, this placement is somewhat arbitrary because the search for information is a dynamic and uneven enterprise that spans multiple STEPS of the IRP. While there is no ‘right time’ to take this STEP for each and every research project, the literature search must begin early on and is often conducted in phases, beginning with (or even preparatory to) STEP 1, defining the problem.”

STEP 5. Develop adequacy in each relevant discipline:

· Explain the meaning of adequacy.

· Develop adequacy in theories.

· Develop adequacy in disciplinary methods.

· Use and evaluate disciplinary methods in basic research.

· Provide in-text evidence of disciplinary adequacy.

Explain the meaning of adequacy:

- Definition: “Adequacy is an understanding of each relevant discipline’s cognitive map, sufficient to identify its perspective on the problem, epistemology, assumptions, concepts, theories, and methods to understand and evaluate its insights concerning the problem … Disciplinary adequacy has two key (and complementary) elements: Understanding (aspects of) the perspectives of each discipline drawn upon; Understanding debates within these disciplines (and thus how insights have been evaluated within the discipline).”

Develop adequacy in theories:

- Adequacy in theories: “Identifying all major theories relevant to the problem is essential to maintaining scholarly rigor and producing an interdisciplinary understanding that is comprehensive … The way to proceed is to identify the major theories relevant to the problem in a single discipline and then repeat this process in serial fashion with the other relevant disciplines until all the important theories are identified.”

Develop adequacy in disciplinary methods:

- Adequacy in disciplines: “Since the evidence on which insights are based is derived from the application of methods, analysis of these insights must involve a familiarity with the potential limitations of those methods.”

Use and evaluate disciplinary methods in basic research:

- Basic research: “The main motivation for interdisciplinarians (whether working solo or in teams) to conduct basic research is to address potential linkages between phenomena studied by different disciplines—linkages that often escape the attention of disciplinary researchers.”

Provide in-text evidence of disciplinary adequacy:

- In-text evidence: “Students need to provide in-text evidence that they have developed adequacy in the disciplines they are using. In-text evidence of disciplinary adequacy may be expressed in many ways, such as statements about the disciplinary elements that pertain to the problem, the disciplinary affiliation of leading theorists, and the disciplinary methods used.”

STEP 6. Analyze the problem and evaluate each insight or theory:

· Analyze the problem from each discipline’s perspective.

· Evaluate the insights produced by each discipline.

Analyze the problem from each discipline’s perspective:

- Definition: “Analyzing the problem from each disciplinary perspective involves moving from one discipline to another and shifting from one perspective to another … Analyzing the problem requires viewing it through the lens of each disciplinary perspective primarily in terms of its insights and theories.”

Evaluate the insights produced by each discipline:

- Evaluation: “Merely evaluating theories from multiple disciplines does not constitute full interdisciplinarity, but only constitutes multidisciplinarity. Full interdisciplinarity is achieved only by continuing the IRP and actually integrating the most important theories as the basis for constructing a more comprehensive understanding of the problem.”

STEP 7. Identify conflicts between insights and their sources:

· Identify conflicting insights.

· Locate sources of conflict among insights.

· Communicate your research to the appropriate audience.

Identify conflicting insights:

- Identify conflicting disciplinary insights: “This is necessary because these conflicts stand in the way of creating common ground and, thus, of achieving integration. The need for integration generally arises out of conflicts, controversies, and differences (whether large or small). Conflicts among insights are generally discovered when conducting the full-scale literature search. Such conflicts may occur within disciplines as well as across disciplines.”

Locate sources of conflict among insights:

- Disciplinary perspective: “The sources of conflict will generally be found in elements of disciplinary perspective. The three most common sources of conflict among insights are concepts, theories, and the assumptions underlying them.”

Communicate your research to the appropriate audience:

- Communication: “Once you have identified all of the relevant insights and theories and have located their sources of conflict, you should communicate this information to the appropriate audience.”

STEP 8. Create common ground between insights:

· Identify the six core ideas about creating common ground.

· Create common ground among conflicting concepts and/or assumptions.

· Create common ground among conflicting ethical positions.

· Create common ground among insights that have a theoretical base.

Identify the six core ideas about creating common ground:

- Definition: “Interdisciplinary common ground involves modifying one or more concepts or theories and their underlying assumptions. Assumptions undergird concepts and theories, which in turn undergird insights. Common ground is not the same as integration, but it is preparatory to and essential for integration … This definition and description of common ground rests on six core ideas that form the basis for creating common ground: Thinking integratively, common ground is created regularly, it is necessary for collaborative communication, it plays out differently in contexts of narrow versus wide interdisciplinarity, it is essential to integration, and it requires using intuition.”

Create common ground among conflicting concepts and/or assumptions:

- Common ground: “Common ground across diverse insights may generate a more comprehensive understanding that is very novel and useful, but may prove to be challenging … At times, the best strategy may not be to seek one shared definition of a term, but rather to clarify the differences between different uses of the same term … Creating common ground does not remove the tension between the concepts and the insights they produce; it does reduce this tension, making integration possible (but not guaranteed).”

Create common ground among conflicting ethical positions:

- Ethical evaluations: “The first occurs during the literature search. Here students should strive not to allow their personal views to skew the selection of insights concerning the issue. As noted earlier, such skewing is a common practice in disciplinary research, not to mention partisan politics and debate, but has no place in quality interdisciplinary work where all relevant viewpoints should be accorded equal voice. The second is made when analyzing the problem (STEP 6). Here students should strive not to allow their personal views to skew their evaluation of insights with which they may disagree. Note that in both cases our views about how the world should work can bias our understanding of how it does work.”

Create common ground among insights that have a theoretical base:

- Theoretical base: “When reading insights that have a theoretical base, you will often encounter models, variables, concepts, and causal relationships. You will need to understand these components of theory as you seek to create common ground … Before trying to create common ground among theories, make certain that the different authors are in fact talking about the same thing. Mapping their arguments enables you to distinguish real conflicts (over the same thing) from apparent conflicts (when authors talk about different things).”

STEP 9. Construct a more comprehensive understanding:

· Be creative.

· Construct the more comprehensive understanding from modified concepts and/or assumptions.

· Construct the more comprehensive theory from a modified theory.

Be creative:

- Definition: “Readers should not be misled into presuming that they will automatically achieve a more comprehensive understanding after performing all STEPS correctly. Instead, researchers need a creative act in which they combine the best elements of disciplinary insights in a novel and useful way. (Note: The standard definition of creativity refers to novelty combined with some sort of usefulness or value.) … The creative person needs to have both ‘synthetic’ skills (to recognize connections that others have missed) and ‘analytical’ skills (to gather and evaluate relevant insights), and to subject the inspirations produced by the subconscious to careful evaluation.”

Construct the more comprehensive understanding from modified concepts and/or assumptions:

- Comprehensive understanding: “Constructing the more comprehensive understanding is carried out by using the common ground created in STEP 8 to integrate the disciplinary insights. Students will need to demonstrate how the modified concept or assumption is inclusive of the others and fits best with the available evidence. The form this more comprehensive understanding takes varies. Narratives are probably more common (along with metaphors and images) in the humanities, whereas theories, models, or simulations are more common in the natural and social sciences.”

Construct the more comprehensive theory from a modified theory:

- Causal/propositional integration: “Causal arguments examine the underlying cause for any particular situation or argument, and analyze what causes a trend, an event, or a certain outcome. Thus propositional integration cannot be distinct from causal integration. As noted elsewhere, our use of the word cause allows for multiple causes. Causal or propositional integration refers to combining truth claims from disciplinary theoretical explanations to form an integrated theory—that is, a new proposition that is interdisciplinary and more comprehensive.”

STEP 10. Reflect on, test, and communicate the understanding:

· Reflect on the more comprehensive understanding or theory.

· Test the quality of interdisciplinary work.

· Test the more comprehensive understanding or theory.

· Communicate the results of integration.

Reflect on the more comprehensive understanding or theory:

- Definition: “Research of any kind calls for reflection. Reflection in an interdisciplinary sense is a self-conscious activity that involves thinking about why certain choices were made at various points in the research process and how these choices have affected the development of the work … While reflection should occur throughout the research process, it is necessary at the end of the research process … Four sorts of reflection that are called for in interdisciplinary work: (1) what has actually been learned from the project, (2) STEPS omitted or compressed, (3) one’s own biases, and (4) one’s limited understanding of the relevant disciplines, theories, and methods.”

Test the quality of interdisciplinary work:

- Test quality: “The learning outcomes typically claimed for interdisciplinarity include tolerance of ambiguity or paradox, critical thinking, a balance between subjective and objective thinking, an ability to demythologize experts, increased empowerment to see new and different questions and issues, and the ability to draw on multiple methods and the knowledge to address them. Notably, interdisciplinarians substantially agree that integration is ‘fundamental to any ‘successful’ interdisciplinary program’ and consider ‘the ability to synthesize or integrate’ as the ‘hallmark of interdisciplinarity’ … The interdisciplinary understanding, then, is new knowledge that is useful, disciplined, integrative, and purposeful. These core premises are the primary indicators of quality interdisciplinary work and form the basis for testing or assessing the quality of the understanding produced.”

Test the more comprehensive understanding or theory:

- Test understanding: “There are four ways to test an interdisciplinary understanding. Three of these look at the results and ask in turn whether there seem to be useful policy implications, whether others find the results interesting, and whether the interdisciplinary understanding is indeed better in some identifiable way. The fourth test looks at the process used to produce the result and asks whether this was appropriate. This fourth test bears some similarity to the practice within disciplines of judging whether disciplinary methods were applied properly in generating a certain result.”

Communicate the results of integration:

- Communicate: “Advanced undergraduate or graduate courses typically encourage or even require students to use metaphors, models, or narratives to capture creatively the new understanding in all of its richness. However one chooses to communicate the new understanding, it should be inclusive of each discipline’s insights but beholden to none of them. That is, each relevant insight, theory, or concept should contribute to the understanding but not dominate it. The objective of this part of STEP 10 is to achieve unity, coherence, and balance among the disciplinary influences that have contributed to the understanding. In effect, the use of metaphors, models, and narratives to communicate the understanding constitutes a test of whether it is coherent, unified, and balanced and, thus, truly interdisciplinary. Other ways to communicate results of integration include a new process, a new product, a critique of existing policy and/or a proposed new policy, and a new question or avenue of scientific inquiry.”

- See all book summaries and book recommendations/reading list