What are mental models? This post defines “mental model” and gives you a list of the top mental model examples for better thinking.

The concepts here are curated from all the major mental model books:

- “The Great Mental Models” by Shane Parrish/Farnam Street

- “Super Thinking” by Gabriel Weinberg & Lauren McCann

- “The Art of Thinking Clearly” by Rolf Dobelli

- “Poor Charlie’s Almanack” by Charlie Munger

- And more!

🧠 For a full list of 90+ mental models (across core thinking, science, physics, chemistry, biology, math, probability/statistics, engineering, and economics) check out Mini Mind: 365 daily emails of bite-size brain food

Post Contents: Click a link here to jump to a section below

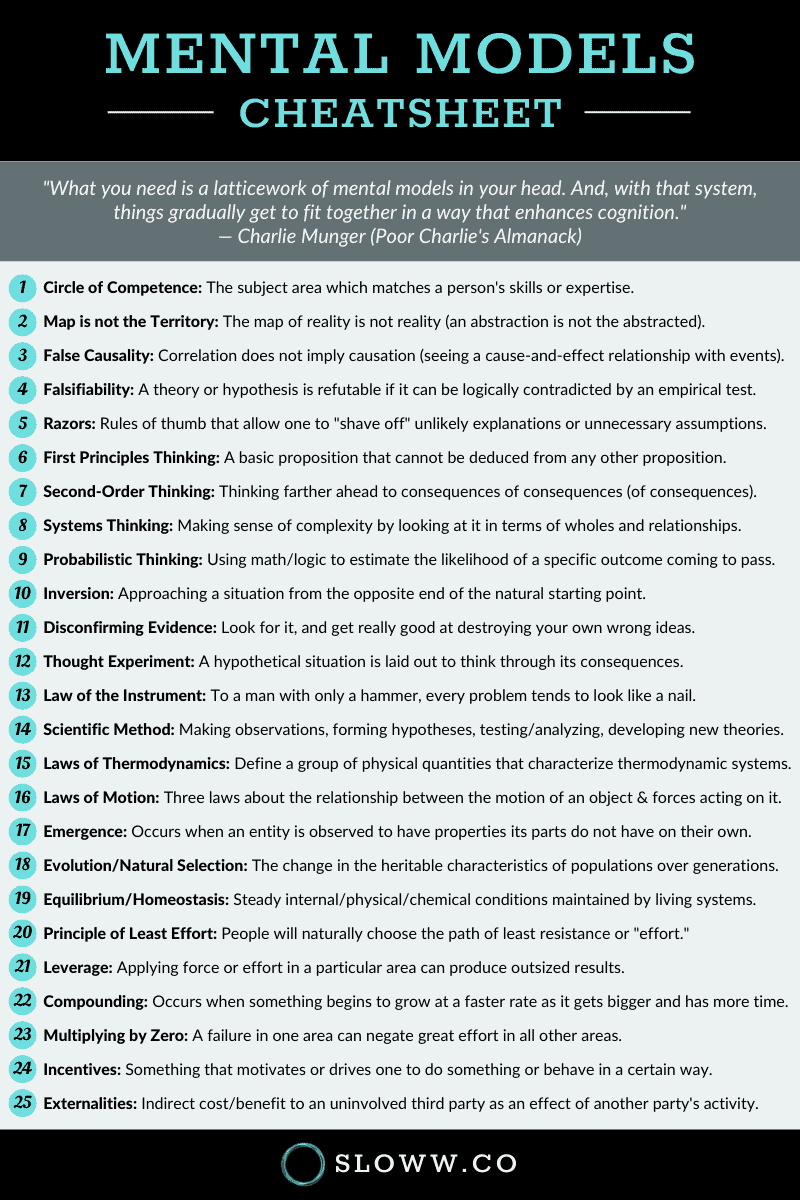

25 Mental Model Examples (+Infographic):

- Circle of Competence

- Map is not the Territory

- False Causality

- Falsifiability

- Razors

- First Principles Thinking

- Second-Order Thinking

- Systems Thinking

- Probabilistic Thinking

- Inversion

- Disconfirming Evidence

- Thought Experiment

- Law of the Instrument

- Scientific Method

- Laws of Thermodynamics

- Laws of Motion

- Emergence

- Evolution / Natural Selection

- Equilibrium / Homeostasis

- Principle of Least Effort

- Leverage

- Compounding

- Multiplying by Zero

- Incentives

- Externalities

25 Mental Models to Master the Art of Thinking (+ Infographic Cheatsheet)

What are Mental Models?

“Recurring concepts are called mental models. Once you are familiar with them, you can use them to quickly create a mental picture of a situation, which becomes a model that you can later apply in similar situations.” — Gabriel Weinberg & Lauren McCann (Super Thinking)

Mental models defined:

- “A mental model is simply a representation of how something works. We cannot keep all of the details of the world in our brains, so we use models to simplify the complex into understandable and organizable chunks.” — Shane Parrish (The Great Mental Models)

- “Mental models shape how we think, how we understand, and how we form beliefs. Largely subconscious, mental models operate below the surface. We’re not generally aware of them and yet they’re the reason when we look at a problem we consider some factors relevant and others irrelevant. They are how we infer causality, match patterns, and draw analogies. They are how we think and reason.” — Shane Parrish (The Great Mental Models)

- “Mental models are a tool set that can help you be wrong less. They are a collection of concepts that help you more effectively navigate our complex world.” — Gabriel Weinberg & Lauren McCann (Super Thinking)

The power of mental models:

- “When you learn to see the world as it is, and not as you want it to be, everything changes. The solution to any problem becomes more apparent when you can view it through more than one lens. You’ll be able to spot opportunities you couldn’t see before, avoid costly mistakes that may be holding you back, and begin to make meaningful progress in your life. That’s the power of mental models.” — Shane Parrish (The Great Mental Models)

- “Better models mean better thinking. The degree to which our models accurately explain reality is the degree to which they improve our thinking.” — Shane Parrish (The Great Mental Models)

- “If you can understand the relevant models for a situation, then you can bypass lower-level thinking and immediately jump to higher-level thinking. In contrast, people who don’t know these models will likely never reach this higher level, and certainly not quickly.” — Gabriel Weinberg & Lauren McCann (Super Thinking)

You need multiple mental models:

- “The first rule is that you’ve got to have multiple models—because if you have just one or two that you’re using, the nature of human psychology is such that you’ll torture reality so that it fits your models, or at least you’ll think it does.” — Charlie Munger (Poor Charlie’s Almanack)

- “(To win in) the game of life, get the needed models into your head and think it through forward and backward.” — Charlie Munger (Poor Charlie’s Almanack)

- “The models have to come from multiple disciplines—because all the wisdom of the world is not to be found in one little academic department.” — Charlie Munger (Poor Charlie’s Almanack)

Becoming multidisciplinary with mental models:

- “When I urge a multidisciplinary approach—that you’ve got to have the main models from a broad array of disciplines and you’ve got to use them all—I’m really asking you to ignore jurisdictional boundaries. And the world isn’t organized that way … If you want to be a good thinker, you must develop a mind that can jump the jurisdictional boundaries.” — Charlie Munger (Poor Charlie’s Almanack)

- “I’ve long believed that a certain system—which almost any intelligent person can learn—works way better than the systems that most people use. What you need is a latticework of mental models in your head. And, with that system, things gradually get to fit together in a way that enhances cognition.” — Charlie Munger (Poor Charlie’s Almanack)

- “A latticework is an excellent way to conceptualize mental models, because it demonstrates the reality and value of interconnecting knowledge. The world does not isolate itself into discrete disciplines. We only break it down that way because it makes it easier to study it. But once we learn something, we need to put it back into the complex system in which it occurs. We need to see where it connects to other bits of knowledge, to build our understanding of the whole. This is the value of putting the knowledge contained in mental models into a latticework.” — Shane Parrish (The Great Mental Models)

25 Top Mental Model Examples

1. Circle of Competence

The subject area which matches a person’s skills or expertise.

- “You’ve got to play within your own circle of competence … Rise quite high in life by slowly developing a circle of competence—which results partly from what you were born with and partly from what you slowly develop through work … In effect, you’ve got to know what you know and what you don’t know. What could possibly be more useful in life than that?” — Charlie Munger (Poor Charlie’s Almanack)

2. The Map is not the Territory

The map of reality is not reality (an abstraction derived from something is not the thing itself).

- “We must use some model of the world in order to simplify it and therefore interact with it. We cannot explore every bit of territory for ourselves. We can use maps to guide us, but we must not let them prevent us from discovering new territory or updating our existing maps.” — Shane Parrish (The Great Mental Models)

3. False Causality

Correlation does not imply causation. “Correlation implies causation” is a questionable-cause logical fallacy when two events occurring together are taken to have established a cause-and-effect relationship.

- “We notice two things happening at the same time (correlation) and mistakenly conclude that one causes the other (causation). We then often act upon that erroneous conclusion, making decisions that can have immense influence across our lives.” — Shane Parrish (The Great Mental Models)

4. Falsifiability

For a theory to be considered scientific, it must be falsifiable. A theory or hypothesis is falsifiable (or refutable) if it can be logically contradicted by an empirical test.

- “Falsification is the opposite of verification; you must try to show the theory is incorrect, and if you fail to do so, you actually strengthen it … The idea here is that if you can’t prove something wrong, you can’t really prove it right either.” — Shane Parrish (The Great Mental Models)

5. Razors

Principles or rules of thumb that allow one to eliminate unlikely explanations for a phenomenon or avoid unnecessary actions.

- “A razor ‘shaves off’ unnecessary assumptions.” — Gabriel Weinberg & Lauren McCann (Super Thinking)

- Occam’s Razor: Entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity (when presented with competing theories/explanations about the same prediction, the simpler one with fewer parameters/assumptions is to be preferred).

- Hanlon’s Razor: Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity.

- Adler’s Razor (or Newton’s Flaming Laser Sword): If something cannot be settled by experiment or observation, then it is not worth debating.

- Hitchens’s Razor: What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence (the burden of proof regarding the truthfulness of a claim lies with the one who makes the claim).

6. First Principles Thinking

A basic proposition or assumption that cannot be deduced from any other proposition or assumption.

- “Thinking from the bottom up, using basic building blocks of what you think is true to build sound (and sometimes new) conclusions. First principles are the group of self-evident assumptions that make up the foundation on which your conclusions rest—the ingredients in a recipe or the mathematical axioms that underpin a formula … When arguing from first principles, you are deliberately starting from scratch.” — Gabriel Weinberg & Lauren McCann (Super Thinking)

7. Second-Order Thinking

Thinking farther ahead and thinking holistically (requiring us to not only consider our actions and their immediate consequences, but the subsequent effects of those actions as well).

- “Almost everyone can anticipate the immediate results of their actions. This type of first-order thinking is easy and safe but it’s also a way to ensure you get the same results that everyone else gets. Second-order thinking is thinking farther ahead and thinking holistically … Thinking in terms of the system in which you are operating will allow you to see that your consequences have consequences.” — Shane Parrish (The Great Mental Models)

8. Systems Thinking

Making sense of the complexity of the world by looking at it in terms of wholes and relationships rather than by splitting it down into its parts.

- “When you attempt to think about the entire system at once. By thinking about the overall system, you are more likely to understand and account for subtle interactions between components that could otherwise lead to unintended consequences from your decisions.” — Gabriel Weinberg & Lauren McCann (Super Thinking)

9. Probabilistic Thinking

Trying to estimate, using some tools of math and logic, the likelihood of any specific outcome coming to pass.

- “In a world where each moment is determined by an infinitely complex set of factors, probabilistic thinking helps us identify the most likely outcomes … Successfully thinking in shades of probability means roughly identifying what matters, coming up with a sense of the odds, doing a check on our assumptions, and then making a decision.” — Shane Parrish (The Great Mental Models)

10. Inversion

Approaching a situation from the opposite end of the natural starting point.

- “‘Invert, always invert,’ Jacobi said. He knew that it is in the nature of things that many hard problems are best solved when they are addressed backward … It is not enough to think problems through forward. You must also think in reverse.” — Charlie Munger (Poor Charlie’s Almanack)

11. Disconfirming Evidence

If you can get really good at destroying your own wrong ideas, that is a great gift.

- “Darwin paid special attention to disconfirming evidence, particularly when it disconfirmed something he believed and loved. Routines like that are required if a life is to maximize correct thinking.” — Charlie Munger (Poor Charlie’s Almanack)

12. Thought Experiment

Hypothetical situation in which a hypothesis, theory, or principle is laid out for the purpose of thinking through its consequences.

- “Thought experiments can be defined as ‘devices of the imagination used to investigate the nature of things’ … Its chief value is that it lets us do things in our heads we cannot do in real life, and so explore situations from more angles than we can physically examine and test for.” — Shane Parrish (The Great Mental Models)

13. Law of the Instrument

Over-reliance on a familiar tool or methods, ignoring or under-valuing alternative approaches.

- “To a man with only a hammer, every problem tends to look pretty much like a nail.” — Charlie Munger paraphrasing Abraham Maslow (Poor Charlie’s Almanack)

14. Scientific Method

Empirical method of acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science. The process in the scientific method involves making conjectures (hypothetical explanations), deriving predictions from the hypotheses as logical consequences, and then carrying out experiments or empirical observations based on those predictions.

- “Formally, the scientific method is a rigorous cycle of making observations, formulating hypotheses, testing them, analyzing data, and developing new theories. But you can also apply it simply by embracing an experimental mindset. The most successful (and adaptive) people and organizations are constantly refining how they work and what they work on to be more effective.” — Gabriel Weinberg & Lauren McCann (Super Thinking)

15. Laws of Thermodynamics

Define a group of physical quantities, such as temperature, energy, and entropy, that characterize thermodynamic systems in thermodynamic equilibrium.

- Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics: If two systems are each in thermal equilibrium with a third system, then they are in thermal equilibrium with each other.

- First Law of Thermodynamics: When energy passes into or out of a system (as work, heat, or matter), the system’s internal energy changes in accord with the law of conservation of energy (energy can be transformed from one form to another, but can neither be created nor destroyed).

- Second Law of Thermodynamics: In a natural thermodynamic process, the sum of the entropies of the interacting thermodynamic systems never decreases (heat does not spontaneously pass from a colder body to a warmer body).

- Third Law of Thermodynamics: A system’s entropy approaches a constant value as the temperature approaches absolute zero.

16. Laws of Motion

Newton’s laws of motion are three laws of classical mechanics that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it.

- First Law of Motion: An object at rest, stays at rest (A body remains at rest, or in motion at a constant speed in a straight line, unless acted upon by a force).

- Second Law of Motion: Force = Mass * Acceleration, or F = ma (When a body is acted upon by a force, the time rate of change of its momentum equals the force).

- Third Law of Motion: For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction (If two bodies exert forces on each other, these forces have the same magnitude but opposite directions).

17. Emergence

Occurs when an entity is observed to have properties its parts do not have on their own (properties or behaviors which emerge only when the parts interact in a wider whole).

- “Higher-level behavior tends to emerge from the interaction of lower-order components. The result is frequently not linear – not a matter of simple addition – but rather non-linear, or exponential. An important resulting property of emergent behavior is that it cannot be predicted from simply studying the component parts.” — Shane Parrish (Farnam Street)

18. Evolution / Natural Selection

Evolution is the change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes that are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Different characteristics tend to exist within any given population as a result of mutation, genetic recombination, and other sources of genetic variation. Evolution occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection (including sexual selection) and genetic drift act on this variation, resulting in certain characteristics becoming more common or rare within a population … Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations.

- “The process that drives biological evolution. It was independently formulated by both Alfred Wallace and Charles Darwin, and later made famous by Darwin’s 1859 book On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. Traits that provide reproductive advantages are naturally selected over generations, making them more prevalent as species evolve to fit their environment. Beyond biological evolution, natural selection also drives societal evolution, the process by which society changes over time.” — Gabriel Weinberg & Lauren McCann (Super Thinking)

19. Equilibrium / Homeostasis

State of steady internal, physical, and chemical conditions maintained by living systems. This is the condition of optimal functioning for the organism and includes many variables, such as body temperature and fluid balance, being kept within certain pre-set limits (homeostatic range).

- “From biology, there is homeostasis, which describes a situation in which an organism constantly regulates itself around a specific target, such as body temperature. When you get too cold, you shiver to warm up; when it’s too hot, you sweat to cool off. In both cases, your body is trying to revert to its normal temperature. That’s helpful, but the same effect also prevents change from the status quo when you want it to occur … When you fight homeostasis—in yourself or in others—look out for the underlying mechanisms that are working against your efforts to make changes.” — Gabriel Weinberg & Lauren McCann (Super Thinking)

20. Principle of Least Effort

Animals, people, and even well-designed machines will naturally choose the path of least resistance or “effort.” The principle of least effort is analogous to the path of least resistance.

- “In a physical world governed by thermodynamics and competition for limited energy and resources, any biological organism that was wasteful with energy would be at a severe disadvantage for survival. Thus, we see in most instances that behavior is governed by a tendency to minimize energy usage when at all possible.” — Shane Parrish (Farnam Street)

21. Leverage

Applying force or effort in a particular area can produce outsized results (relative to similar applications of force or effort elsewhere). A lever amplifies an input force to provide a greater output force, which is said to provide leverage.

- “The mechanical advantage gained by a lever, also known as leverage, serves as the basis of a mental model applicable across a wide variety of situations. The concept can be useful in any situation where applying force or effort in a particular area can produce outsized results, relative to similar applications of force or effort elsewhere … As applied to individuals, certain activities or actions have much greater leverage than others, and spending time or money on these high-leverage activities will produce the greatest effects. Therefore, you should take time to continually identify high-leverage activities. It’s getting more bang for your buck … As a rule, the highest leverage activities have the lowest opportunity cost.” — Gabriel Weinberg & Lauren McCann (Super Thinking)

22. Compounding

Occurs when something begins to grow at a faster rate as it gets bigger and has more time. Compound interest is the addition of interest to the principal sum of a loan or deposit, or in other words, interest on interest. It is the result of reinvesting interest, rather than paying it out, so that interest in the next period is then earned on the principal sum plus previously accumulated interest.

- “It’s been said that Einstein called compounding a wonder of the world. He probably didn’t, but it is a wonder. Compounding is the process by which we add interest to a fixed sum, which then earns interest on the previous sum and the newly added interest, and then earns interest on that amount, and so on ad infinitum. It is an exponential effect, rather than a linear, or additive, effect. Money is not the only thing that compounds; ideas and relationships do as well. In tangible realms, compounding is always subject to physical limits and diminishing returns; intangibles can compound more freely. Compounding also leads to the time value of money, which underlies all of modern finance.” — Shane Parrish (Farnam Street)

23. Multiplying by Zero

A failure in one area can negate great effort in all other areas.

- “Any reasonably educated person knows that any number multiplied by zero, no matter how large the number, is still zero. This is true in human systems as well as mathematical ones. In some systems, a failure in one area can negate great effort in all other areas. As simple multiplication would show, fixing the ‘zero’ often has a much greater effect than does trying to enlarge the other areas.” — Shane Parrish (Farnam Street)

24. Incentives

Something that motivates or drives one to do something or behave in a certain way. Intrinsic incentives are those that motivate a person to do something out of their own self interest or desires, without any outside pressure or promised reward. Extrinsic incentives are motivated by rewards such as an increase in pay for achieving a certain result; or avoiding punishments such as disciplinary action or criticism as a result of not doing something.

- “As usual in human affairs, what determines the behavior are incentives for the decision maker … getting the incentives right is a very, very important lesson … Appeal to interest and not to reason if you want to change conclusions … Another thing to avoid is being subjected to perverse incentives. You don’t want to be in a perverse incentive system that’s rewarding you if you behave more and more foolishly, or worse and worse. Perverse incentives are so powerful as controllers of human cognition and human behavior that one should avoid their influence.” — Charlie Munger (Poor Charlie’s Almanack)

25. Externalities

An indirect cost or benefit to an uninvolved third party that arises as an effect of another party’s (or parties’) activity. Externalities can be considered as unpriced goods involved in either consumer or producer market transactions. Air pollution from motor vehicles and water pollution from mills and factories are examples (we are all made worse off by pollution but are not compensated by the market for this damage). A positive externality is when an individual’s consumption in a market increases the well-being of others, but the individual does not charge the third party for the benefit.

- “Consequences, good or bad, that affect an entity without its consent, imposed from an external source … Addressing negative externalities is often referred to as internalizing them. Internalizing is an attempt to require the entity that causes the negative externality to pay for it.” — Gabriel Weinberg & Lauren McCann (Super Thinking)

🧠 For a full list of 90+ mental models (across core thinking, science, physics, chemistry, biology, math, probability/statistics, engineering, and economics) check out Mini Mind: 365 daily emails of bite-size brain food

You May Also Enjoy:

- “Super Thinking” by Gabriel Weinberg & Lauren McCann: Book Summary + 🔒Premium Summary

- “The Art of Thinking Clearly” by Rolf Dobelli: Book Summary + 🔒Premium Summary