“Post-work is about the future, but it is also bursting with the past’s lost possibilities.” — Andy Beckett¹

I always find it mind-opening and expanding to think about the future—I’ve covered the future of busyness, but what about something as life-dominating as work?

Here’s some quick work-life math: On the low end, work is 34 percent of all your waking hours for 40 years—and that’s if you put in a flat 40 hours per week during your entire career. If just goes up from there if you work more or factor in time getting ready, time commuting, time thinking about work outside of work, etc.

Can you really blame people for wanting a third of all their time awake to be more meaningful and fulfilling? And, if it can’t be more meaningful and fulfilling, can you blame them for wanting to find ways to reduce the total amount of time they spend working in general?

There’s a lot already out there about post-work as it relates to politics, universal basic income (UBI), etc. The viewpoint that I’d like to present in this post is from a higher, macro perspective of humanity as a whole.

A Brief History of Work—How we Arrived at Workism & Total Work

“Work is the master of the modern world.”¹

The History of Work

I’ve previously written about the history of work and busyness. Here are some noteworthy highlights to get you up to speed:

- In ancient times, energy had to be conserved and purposefully used in a struggle for survival. Does evolution explain why we have excess energy today that we need to release through purposeful action?

- As far back as the 1st century, Seneca the Younger observed how people—especially the wealthy—rushed through life.

- “The word school…comes from skholē, the Greek word for ‘leisure.’ ‘We used to teach people to be free…Now we teach them to work.’“5

- “The modern age opened; I think, with the accumulation of capital which began in the sixteenth century…From the sixteenth century, with a cumulative crescendo after the eighteenth, the great age of science and technical inventions began, which since the beginning of the nineteenth century has been in full flood.” — John Maynard Keynes

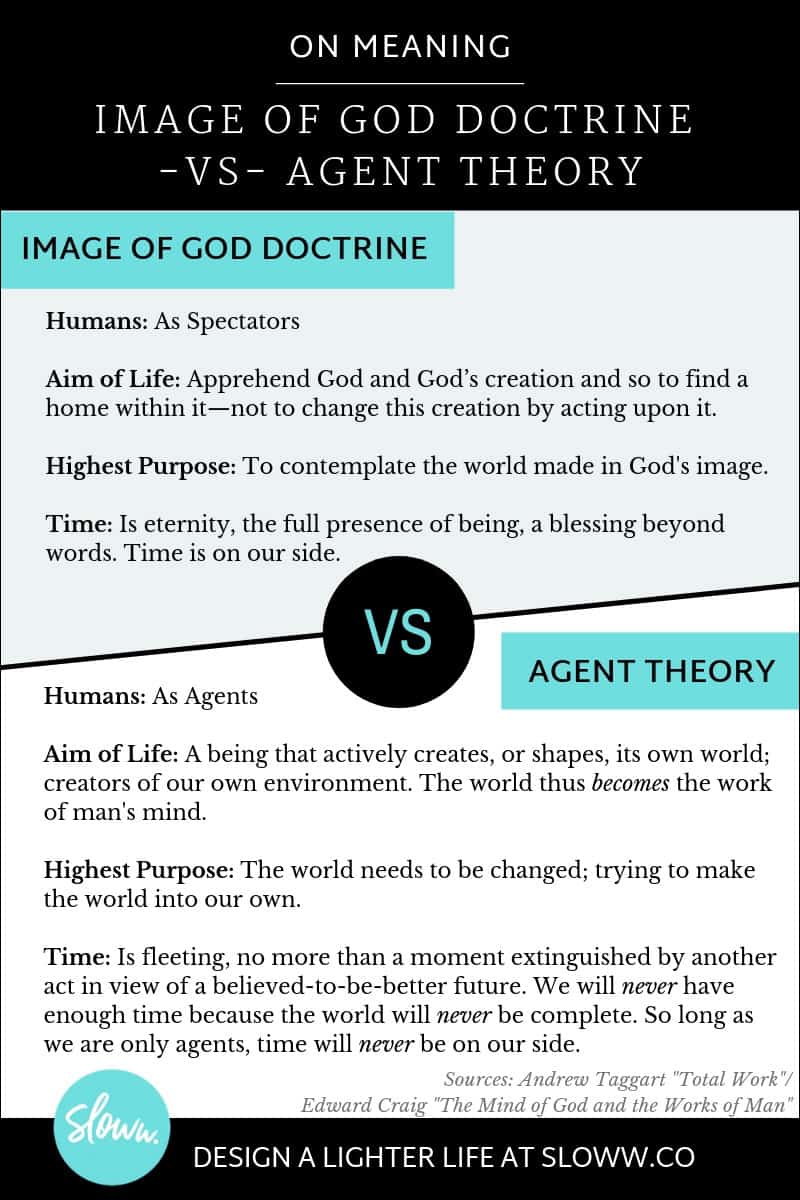

- In the 18th century, time began being used to coordinate and synchronize work/labor. With the Industrial Revolution (1760-1840), time became money. Productivity started to become top priority over leisure. It was during the 18th century that a world-changing historical transition occurred: “human beings left behind the idea that their highest purpose was to contemplate the world (called the ‘Image of God’ doctrine) and instead embraced the groundbreaking idea that the world needs to be changed (called the ‘Agent Theory’).” — Andrew Taggart9

- In the 19th century, the Protestant work ethic that every able-minded/bodied person is expected to work evolved to the right to work.

- In 1835, Alexis de Tocqueville, a French diplomat, political scientist and historian, released Democracy in America observing and confirming American busyness.

- In 1899, Thorstein Veblen released The Theory of the Leisure Class, acknowledging leisure-as-status and introduced the concepts of “conspicuous consumption” and “conspicuous leisure.”

- “In the 20th century…we assume that full-time gainful employment in the labor force is precisely what is expected of each human being…For the first time in human history…work itself becomes meaningful.” — Andrew Taggart

- In 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted “three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week” by 2030 in his essay Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren.

- In 1932, Bertrand Russell says a 4-hour workday should be enough work for everybody in his essay In Praise of Idleness.

- In 1970, Staffan B. Linder, a Swedish economist, coins the phrase “the harried leisure class.”

- In 1971, Wayne Oates, an American psychologist, coins the term “workaholic.”

- In 1975, American sociologist Max Kaplan noted that US work hours had been declining almost 4 hours per week each decade between 1875-1975 (from 70 hours/week to 37 hours/week over the course of that century) due to automation. Since 1970, work hours have flatlined around 40 hours/week for the last 5 decades.

The Current State of Work

Humans have always been busy throughout history, but busyness itself has changed. Over the course of the last century, industrial/production work has decreased with automation. But, service/knowledge work has increased to become the majority of total employment.

- “The factory logic of mass production forced people to come to where the machines were. In knowledge work, the machines are where the people are.”4 — Esko Kilpi

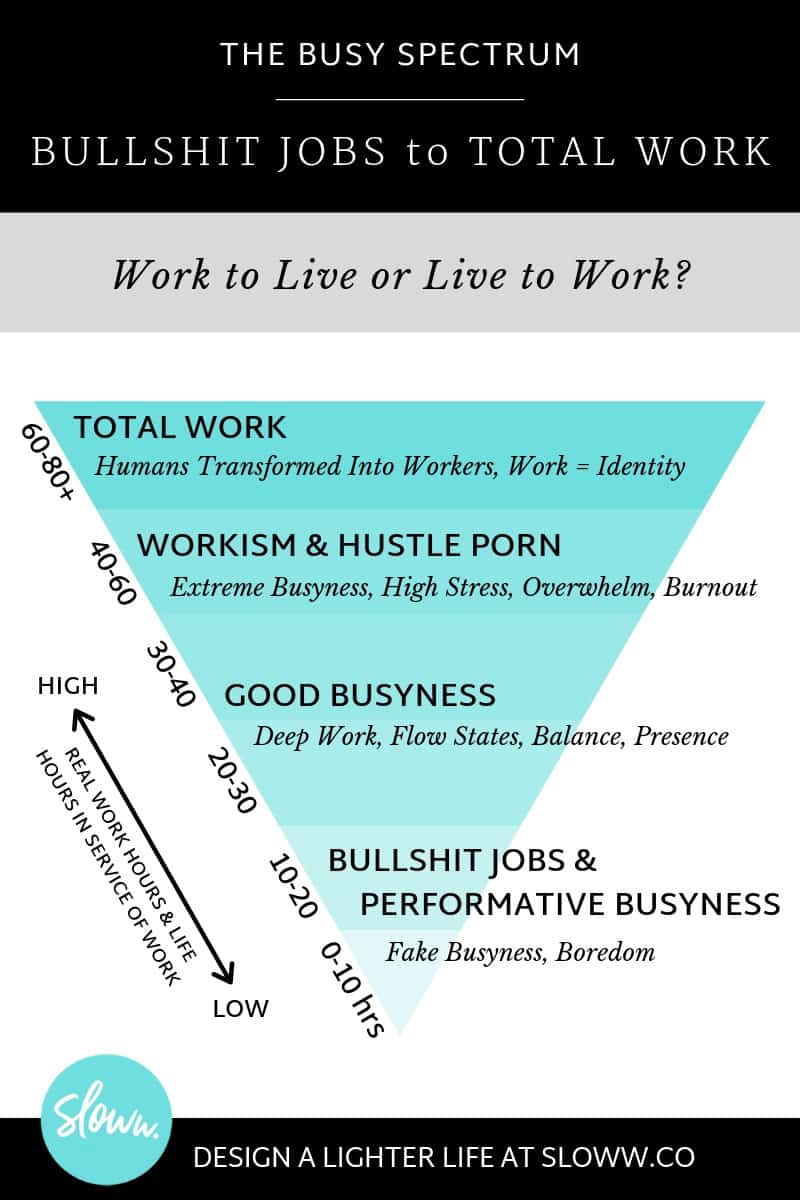

This has led to a vast difference in how “busyness” is experienced and defined: a spectrum of those who spend the majority of their days pretending to be busy to those who worship busyness and work 60-80+ hour weeks (see “busy spectrum” image below).

- On the low end of the busyness spectrum, you have people doing real work for an average of 2 hours and 53 minutes per day while distracted and/or pretending to be busy for the rest of the work day.7

- David Graeber, anthropologist and author of Bullshit Jobs: A Theory, describes this phenomenon of bullshit jobs—new industries have popped up that “only exist because everyone else is spending so much of their time working in all the other ones.”

- A research study called The Conspicuous Consumption of Time shows that busyness is currently a status symbol and concluded: “A busy and overworked lifestyle, rather than a leisurely lifestyle, has become an aspirational status symbol in America.”

- On the high end of the busyness spectrum, you have workism and total work.

- Derek Thompson, author and writer at The Atlantic, describes workism as: “The belief that work is not only necessary to economic production, but also the centerpiece of one’s identity and life’s purpose; and the belief that any policy to promote human welfare must always encourage more work.”

- Thompson describes the evolution/shift of work like this (paraphrased):

- Work was material production, jobs, careers, necessity, status, physical, work to play, work to live

- Work is now identity production, callings, meaning, transcendence, emotional, spiritual, work is play, work is life

- The epitome of workism is “total work.” Andrew Taggart, a practical philosopher, says: “‘Total work’ is the process by which human beings are transformed into workers and nothing else. By this means, work will ultimately become total, I argue, when it is the centre around which all of human life turns; when everything else is put in its service; when leisure, festivity and play come to resemble and then become work; when there remains no further dimension to life beyond work; when humans fully believe that we were born only to work; and when other ways of life, existing before total work won out, disappear completely from cultural memory.”8

- “Work is … how we give our lives meaning when religion, party politics and community fall away.” — Joanna Biggs¹

You can see how the history of work, human evolution, evolving definitions of meaning (for work and life), and technological advancement brought us to where we are today.

But, the big question is, where do we go from here?

- “Post-work may be a rather grey and academic-sounding phrase, but it offers enormous, alluring promises: that life with much less work, or no work at all, would be calmer, more equal, more communal, more pleasurable, more thoughtful, more politically engaged, more fulfilled – in short, that much of human experience would be transformed.” — Andy Beckett¹

The Future of Post-Workism & Total Work—5 Future Scenarios when the Religion of Work Loses Followers

“The role of work has changed profoundly before. It’s going to change again. It’s probably already in the process of changing.” — Benjamin Hunnicutt¹

I’ve seen “post-work” or “post-workism” being interpreted with at least five different scenarios:

- A future with no work

- A future with less work

- A future with a shift to different work

- A future with more purposeful, fulfilling work

- A future with work less central—life first, work second (reprioritized work)

In my mind, this scenario requires the shortest explanation of all five. Personally, I don’t believe that post-workism will be a future with no work at all. To Derek Thompson’s point:

- “Humankind has not yet invented itself out of labor.”

And, no doubt about it, life will always require action. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs still applies, and no one can argue about the bottom of the pyramid—we need to eat:

- “If the hand does nothing, the mouth does not chew.” — Dani tribe elders

As I’ll outline in a bit, I don’t think it’s a matter of ending work as much as it’s about redefining and reprioritizing work. There’s plenty of positive “work” to be done like caregiving and maintaining things.

Fair warning: This is by far the longest scenario.

As we covered earlier, there are already plenty of people actually only working a 15-hour workweek. Couldn’t we just acknowledge this reality and restructure around less work? Shouldn’t this be virtually common sense given that work doesn’t naturally come in 8-hour days, 5 days a week, for 50 weeks out of the year? Think about how “work” used to be on as-needed basis (hunting/gathering) and seasonal (planting/harvesting).

David Graeber concludes that the “system was never consciously designed” and has some hypotheses:

- “Technology has been marshaled, if anything, to figure out ways to make us all work more.”

- “It’s as if someone were out there making up pointless jobs just for the sake of keeping us all working.”

- “The answer clearly isn’t economic: it’s moral and political. The ruling class has figured out that a happy and productive population with free time on their hands is a mortal danger…And, on the other hand, the feeling that work is a moral value in itself, and that anyone not willing to submit themselves to some kind of intense work discipline for most of their waking hours deserves nothing, is extraordinarily convenient for them.”

Graeber isn’t alone. Benjamin Hunnicutt, a professor and historian who has studied work in the west for 50 years, says:

- “I do think there is a fear of freedom – a fear among the powerful that people might find something better to do than create profits for capitalism.”¹

Let’s look at both of Graeber’s key points:

- 2a: Does work have moral value in itself?

- 2b: Is a mass amount of people with more free time a problem?

Revisit the history of work outlined above in this post. In all of recorded human history, it wasn’t until the 20th century that work itself became meaningful. And now, in the 21st century, we see work attempting to become so meaningful that it’s becoming synonymous with human identity. Yet, before the 20th century, this was not the case. So, one could argue that the majority of human history has viewed work as not meaningful (or at least less meaningful).

It’s interesting to study the people who lived during this specific transition in the 20th century—people like John Maynard Keynes and Bertrand Russell.

The economic predictions made by John Maynard Keynes in his 1930 essay Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren have been incredibly accurate almost a century later. Keynes asks a key question that helps us understand the moral value of work: What happens when the economic problem is solved?

- “The economic problem is not—if we look into the future—the permanent problem of the human race.”

- “When the accumulation of wealth is no longer of high social importance, there will be great changes in the code of morals. We shall be able to rid ourselves of many of the pseudo-moral principles which have hag-ridden us for two hundred years, by which we have exalted some of the most distasteful of human qualities into the position of the highest virtues.”

- “We shall once more value ends above means and prefer the good to the useful. We shall honour those who can teach us how to pluck the hour and the day virtuously and well, the delightful people who are capable of taking direct enjoyment in things.”

- “Thus for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem—how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.”

Truly powerful words and an optimistic, hopeful view of the future. Work isn’t mankind’s permanent problem.

Another thing that has stuck with me is Bertrand Russell’s 1932 essay In Praise of Idleness (or, what I believe is a more appropriate title, In Praise of Wise Leisure). Russell offers a scathing definition of work:

- “First of all: what is work? Work is of two kinds: first, altering the position of matter at or near the earth’s surface relatively to other such matter; second, telling other people to do so. The first kind is unpleasant and ill paid; the second is pleasant and highly paid.”

- “The fact is that moving matter about, while a certain amount of it is necessary to our existence, is emphatically not one of the ends of human life.”

- “I think that there is far too much work done in the world, that immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous, and that what needs to be preached in modern industrial countries is quite different from what always has been preached.”

- “The morality of work is the morality of slaves, and the modern world has no need of slavery.”

Pretty clear: Work is not one of the ends of human life, there’s too much work being done, and the belief that work is virtuous causes immense harm.

Buckminster Fuller, inventory and futurist (among many other things), seemed to agree as well:

- “We should do away with the absolutely specious notion that everybody has to earn a living. It is a fact today that one in 10,000 of us can make a technological breakthrough capable of supporting all the rest. The youth of today are absolutely right in recognizing this nonsense of earning a living. We keep inventing jobs because of this false idea that everybody has to be employed at some kind of drudgery because, according to Malthusian Darwinian theory, he must justify his right to exist. So we have inspectors of inspectors and people making instruments for inspectors to inspect inspectors. The true business of people should be to go back to school and think about whatever it was they were thinking about before somebody came along and told them they had to earn a living.”6

Decades later, new voices are preaching the same message.

Benjamin Hunnicutt says:

- “(American society has) an irrational belief in work for work’s sake.”5

David Graeber says:

- “We have a really, really twisted idea of the value of work. There was a time that people thought that work produces something; all value comes from labor. The labor theory of value is almost universally accepted in the 19th century, but they had a very silly focus on factory work, craftsman, production. But, most work isn’t production. Most work is caregiving, most work is maintaining things. As I always say, ‘You make a cup once; you wash it like a thousand times.’ Most work is keeping things the same, it’s not recreating things.”

Andrew Taggart, who is building on philosopher Josef Pieper’s concept of “total work,” says:

- “If meaning, understood as the ludic interaction of finitude and infinity, is precisely what transcends, here and now, the ken of our preoccupations and mundane tasks, enabling us to have a direct experience with what is greater than ourselves, then what is lost in a world of total work is the very possibility of our experiencing meaning. What is lost is seeking why we’re here.”8

Ultimately, the moral value and meaning of work need to ladder up to—and align with—the meaning of life itself.

We won’t go down that road too much here, but I’d start with Andrew Taggart’s description of the world-changing historical transition that occurred in the 18th century from the “Imagine of God Doctrine” to the “Agent Theory” (see summary image below).

Which do you believe? Your belief at this level will have a big influence on your perceived meaning of work:

There is a gaping spiritual void in the Western world. People have turned to things like workism, materialism, and consumption to build bridges across this void—but after enough time, these bridges deteriorate and collapse. Personally, “Agent Theory” was a dead end for me and led to an existential crisis—I’m now a believer in the “Image of God Doctrine” and what Keynes, Russell, Fuller, and all the modern voices here are preaching.

- “Satan finds some mischief still for idle hands to do.” — Isaac Watts

That’s a well-known adage, but is it true?

Derek Thompson says:

- “The paradox of work is that many people hate their jobs, but they are considerably more miserable doing nothing.”5

- “In 1989, the psychologists Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Judith LeFevre conducted a famous study of Chicago workers that found people at work often wished they were somewhere else. But in questionnaires, these same workers reported feeling better and less anxious in the office or at the plant than they did elsewhere. The two psychologists called this ‘the paradox of work’: many people are happier complaining about jobs than they are luxuriating in too much leisure.”5

With this question about too much free time being problematic, we are able to add some practicality to the purely philosophical. We can even add published research into the mix: Idleness Aversion and the Need for Justifiable Busyness10 and Idleness vs Busyness11. Some highlights include:

- “We propose that people have two concurrent, yet paradoxical and conflicting, desires: They (a) dread idleness and desire busyness, but (b) need reasons for their busyness and will not voluntarily choose busyness without some justification.”10

- “While it has been long presumed that people engage in activities in order to pursue goals, we posit a reverse causality: people pursue goals in order to engage in activities.”11

- “People often say they work hard so that they can be idle. Increasing empirical evidence suggests an alternative interpretation — we work hard to avoid being idle. Unlike other resources, time is non-stoppable, non-transferrable, and non-renewable. An individual’s consumption of time is essentially the individual’s use of life. In idleness, time breeds misery. In busyness, time generates happiness, as long as it is used toward a purpose, even a feebly justifiable one.”11

While I believe extended periods of idleness or listlessness can be problematic, it’s important to note that idleness and listlessness are not synonymous with leisure and contemplation.

Let’s go back to the 20th century again. Sixteen years after Bertrand Russell’s In Praise of Idleness, philosopher Josef Pieper published Leisure: The Basis of Culture. Pieper says:

- “The opposite of acedia (despair of listlessness) is not the industrious spirit of the daily effort to make a living, but rather the cheerful affirmation by man of his own existence, of the world as a whole, and of God — of Love, that is, from which arises that special freshness of action, which would never be confused by anyone (who has) any experience with the narrow activity of the ‘workaholic.'”11

- “The ability to be ‘at leisure’ is one of the basic powers of the human soul. Like the gift of contemplative self-immersion in Being, and the ability to uplift one’s spirits in festivity, the power to be at leisure is the power to step beyond the working world and win contact with those superhuman, life-giving forces that can send us, renewed and alive again, into the busy world of work…”11

Of course, the topic of “less work” would not be complete without addressing everyone’s favorite topic these days: automation. But, automation and technological unemployment have been on the horizon for the better part of at least a century.

John Maynard Keynes mentioned “technological unemployment” in 1930:

- “We are being afflicted with a new disease of which some readers may not yet have heard the name, but of which they will hear a great deal in the years to come—namely, technological unemployment. This means unemployment due to our discovery of means of economising the use of labour outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labour.”

Bertrand Russell mentioned “modern technic” back in 1932:

- “Modern technic has made it possible for leisure, within limits, to be not the prerogative of small privileged classes, but a right evenly distributed throughout the community.”

- “The road to happiness and prosperity lies in an organized diminution of work.”

- “Good nature is, of all moral qualities, the one that the world needs most, and good nature is the result of ease and security, not of a life of arduous struggle. Modern methods of production have given us the possibility of ease and security for all; we have chosen instead to have overwork for some and starvation for others. Hitherto we have continued to be as energetic as we were before there were machines. In this we have been foolish, but there is no reason to go on being foolish for ever.”

Although society hasn’t yet seen the implications of widespread automation, I do believe that the horizon is closing in and this is going to happen.

The problem of work distribution is yet to be resolved:

- “Work is badly distributed. People have too much, or too little, or both in the same month.”¹

I’m personally very excited and optimistic about this scenario. I think a shift to different work is long overdue. How could this play out?

On one hand, you have people awakening to the ridiculousness of bullshit jobs along with the involuntary displacement caused by automation. On the other hand, let’s run with the prediction that the normal workweek doesn’t get shorter. So, what are all these people going to do?

Remember David Graeber’s perspective? Most work isn’t production—it’s caregiving and maintaining things. So, could this scenario bring about a course-correction in the type of work we do?

Duane Elgin, author of Voluntary Simplicity, says:

- “Although the consumer and material goods sectors would contract, the service and public sectors (education, health care, urban renewal) would expand dramatically. When we look around at the condition of the world, we see a huge number of unmet needs: caring for the elderly, restoring the environment, educating illiterate and unskilled youth, repairing decaying roads and infrastructure, providing health care, creating community markets and local enterprises, retrofitting the urban landscape for sustainability, and many more. Because there are enormous numbers of unmet needs, there are equally large numbers of purposeful and satisfying jobs waiting to get done.”

Notice the words Elgin uses that are similar to Graeber’s: caring for, restoring, educating, repairing, etc. There’s so much important yet neglected work in the world today to promote what Elgin calls “public well-being.”

The modern art of living means people will start taking responsibility for—and control of—their own individual lives. Elgin says:

- “Traditional political and economic perspectives fail to recognize the most radical change of all in a free-market economy and democratic society: the empowerment of individuals to consciously take charge of their own lives and to begin changing their manner of work, patterns of consumption, forms of governance, modes of communication, and much more.”

Esko Kilpi, who writes and advises individuals and organizations on post-industrial work, says:

- “The aim is to do meaningful things with meaningful people utilizing networks and voluntary participation. It is not the corporation that is in the center, but the intentions and choices of individuals.”³

Ronald Inglehart, who has been leading the work on the World Values Survey, has seen humanity’s values shifting over time:

- “Emphasis is shifting from economic achievement to postmaterialist values that emphasize individual self-expression, subjective well-being, and quality of life. As well, people in these nations are placing less emphasis on organized religion and more emphasis on discovering their inner sense of meaning and purpose in life.”

So, while this scenario may start with involuntary displacement (forcing involuntary simplicity), I believe we’ll also see more people opting for voluntary simplicity to take more control over their own lives. People will involuntarily and voluntarily redefine meaning and identity—in work and life.

Aside from the headlines about automation, finding meaning and purpose at work is probably the hottest topic in the news today.

Derek Thompson says:

- “If technology replaces great swaths of work that is terrible, it might open up the possibility that we have room to find jobs that align with purpose, with fulfillment.”5

Most people have come across the Gallup employee engagement research one way or another. The 2018 results showed that 13 percent of workers are actively disengaged, and:

- “53% of workers are in the ‘not engaged’ category. They may be generally satisfied but are not cognitively and emotionally connected to their work and workplace; they will usually show up to work and do the minimum required but will quickly leave their company for a slightly better offer.”12

If you do the math, that leaves 34 percent that are engaged at work. One third. That’s it. And, this is “good news” to some—it ties the highest engagement rate ever since Gallup starting tracking this two decades ago. Yikes. I can’t think of anything else off the top of my head where a score of 34 percent is a good thing.

You know things are bad when people are literally hacking work. That’s essentially what FIRE (Financial Independence Retire Early) is doing. People aren’t happy doing what they’re doing (working at their primary, paying, day job), so they’ve created a way to stop doing that as soon as possible so they can do what they want to do instead. The leading voice of the movement is Mr. Money Mustache who says:

- “Work is better when you don’t need the money.”

Stowe Boyd, a work ecology and futurist, believes:

- “Perhaps, today, in the twenty-first century, we can evolve into new patterns of organization — in work and society — where the talents, purpose, and long-term needs of all participants can be channeled to be sustainable, productive, and mutually-beneficial, and without the heavy hand of a class of leaders calling the shots. And of course, the cult of leadership couldn’t continue to flourish without the support of a class of leadership-obsessed followers spouting workist dogma, and dreaming of becoming leaders themselves one day.”²

Use of time will change with future economic and technological advancements—just like John Maynard Keynes said about mankind’s permanent problem—but the eternal pursuit of purpose will remain:

- “A sound understanding of idleness and busyness is particularly relevant for the development of future human societies in which technological advances will pose increasing challenges on the constructive uses of time and the pursuit of purposefulness for individual existence. In the recent past of human history when productivity was low, people had to work hard to survive. Idleness was a luxury for the rich. Modernization has elongated people’s lifespan, freed many from devoting most of their time for survival needs, and increased their freedom over the discretionary use of time and the pursuit of purposefulness. As technologies advance further, more of us will be made somewhat useless by AI doctors, driverless cars, and robotic waiters, among others. The day that most of us will not have to work is approaching. Nonetheless, the eternal search for a productive and purposeful life will not cease in future human societies. With progressively less need to work, how can people use their abundance of time purposefully? Engaging in sports and games, self-development, scientific research, hobbies, or destructive behaviors? As we move forward, it ought to be understood that the relative affluence of time does not guarantee the ultimate freedom of human existence, but rather escalates the need for purposeful busyness.” — Idleness vs Busyness11

If you consider a spiritual perspective, Eckhart Tolle says some people are already experiencing this today:

- “As tribal cultures developed into the ancient civilizations, certain functions began to be allotted to certain people: ruler, priest or priestess, warrior, farmer, merchant, craftsman, laborer, and so on. A class system developed. Your function, which in most cases you were born into, determined your identity, determined who you were in the eyes of others, as well as in your own eyes. Your function became a role, but it wasn’t recognized as a role: It was who you were, or thought you were. Only rare beings at the time, such as the Buddha or Jesus, saw the ultimate irrelevance of caste or social class, recognized it as identification with form and saw that such identification with the conditioned and the temporal obscured the light of the unconditioned and eternal that shines in each human being. In our contemporary world, the social structures are less rigid, less clearly defined than they used to be. Although most people are, of course, still conditioned by their environment, they are no longer automatically assigned a function and with it an identity. In fact, in the modern world, more and more people are confused as to where they fit in, what their purpose is, and even who they are.”

Let’s end this scenario with quite possibly the most practical perspective on purpose of all—the Ikarians from one of the Blue Zones where people live to be 100+ years old. The Ikarians get my vote for the most sane humans on the planet: long healthy life, minimal impact on the planet, meaningful relationships (“us” vs. “me”), plant-based diets, drink wine and tea with family and friends, clear purpose based on satisfying low-level needs, no care about time, walkable communities, gardening, enjoy physical work and find joy in everyday chores, enjoy being outside, etc. The popular purpose concept, ikigai, comes from the Blue Zone in Okinawa, Japan.

If we revert to the “Image of God Doctrine”—and get back to the presence of contemplating life and simply finding a home within the world—maybe our individual purposes don’t have to be some lofty goal. Perhaps some people, like the Ikarians, have already figured it all out.

To me, this scenario just makes sense—especially when you factor in social inequality and finite planetary resources. How could work—or the economy for that matter—possibly come first?

- “Priorities must be Planet-Society-Economy as opposed to Economy-Society-Planet…The reality of the world we live in is that the economy is the wholly owned subsidiary of the biosphere.” — Ron Garan, Astronaut

For this scenario to play out, busyness as a status symbol needs to run its course—as all status symbols eventually do. Busyness may not last as long as other status symbols given the negative physical and mental health effects that are already being researched. The glorification of busy will (hopefully) come to an end when people get “sick and tired of being sick and tired” and/or busyness becomes so common that it’s no longer aspirational. Money wealth may shift to a priority on time wealth (or time affluence):

- “Decades from now, perhaps the 20th century will strike future historians as an aberration, with its religious devotion to overwork in a time of prosperity, its attenuations of family in service to job opportunity, its conflation of income with self-worth.”5

More people are waking up to the truth of the American Dream and (lack of) socioeconomic mobility. Not only does the belief of the American Dream not match reality, but we are trading our leisure time for more work in pursuit of the myth. What happens when more people say, “No thanks” to worshipping work?

- “The post-workists argue that Americans work so hard because their culture has conditioned them to feel guilty when they are not being productive, and that this guilt will fade as work ceases to be the norm.”5

Ultimately, Derek Thompson believes that maybe the solution is to simply make work less central to life:

- “Work is not life’s product, but its currency. What we choose to buy with it is the ultimate project of living.”

Andrew Taggart also questions whether work should be at the center of life:

- “To begin with, we could critique the supreme value of work—questioning, for example, whether work shall be a calling for all of us. What if, I wonder, work needn’t be at the center of a life well-lived?”

- “Second, we could dis-identify from the work that we’re doing. Saying to ourselves, ‘Whoever I fundamentally, truly, ultimately am, I am not what I do for a living.’ Indeed, let that be our personal mantra: ‘I am not my work.'”

- “These things create space, which can be filled with vita contemplativa: the contemplative life. Love, joy, art, beauty, philosophy, wonderment, religion, spirituality, going beyond ego and puts us in touch with a greater abiding reality.”

There’s still “work” to be done in Taggart’s utopian vision—he calls it “sustaining life” or “infrastructure” that makes the good life of leisure and contemplation possible. It includes two types of work:

- Human Work—Functions in accordance with natural rhythms: care, responsibility, fineness

- Machine Work—Drudgery tasks, physical labor, mindless mind-work tasks

John Maynard Keynes also looked forward to humanity’s greatest change:

- “I look forward, therefore, in days not so very remote, to the greatest change which has ever occurred in the material environment of life for human beings in the aggregate.”

- “Meanwhile there will be no harm in making mild preparations for our destiny, in encouraging, and experimenting in, the arts of life as well as the activities of purpose.”

- “It will be those peoples, who can keep alive, and cultivate into a fuller perfection, the art of life itself and do not sell themselves for the means of life, who will be able to enjoy the abundance when it comes.”

That sounds pretty perfect to me. I’d like to cultivate the art of life itself:

- “A master in the art of living draws no sharp distinction between his work and his play, his labour and his leisure, his mind and his body, his education and his recreation. He hardly knows which is which. He simply pursues his vision of excellence through whatever he is doing and leaves others to determine whether he is working or playing. To himself he always seems to be doing both.” — L. P. Jacks

Post-Workism Concluding Thoughts (from all the Conclusions)

After putting all of this together, I guess you could say that I believe:

- The future isn’t about no work or even less work (at least anytime soon)

- The future is about reprioritized, different work. The moral value of work will continue to be challenged, automation will allow for shifts to previously neglected work like public well-being related to people and the environment, and we will redefine meaning and identity for ourselves. Work will lose its #1 central position to the rightful #1: life. Both work and life will be more purposeful and fulfilling.

I believe all roads lead to simplicity and spirituality (“simple living, high thinking”). I believe in a future where humanity evolves through (and to) simplicity and consciousness. Course-correcting isn’t taking a step backward—downshifting is upshifting.

Are we here on this planet to learn how to work or learn how to live? If you take a spiritual approach, we all have the same purpose: be one with life. If you take a religious perspective, this life is simply a test for what comes next. Either way, we are human beings, not human doings.

Humans are highly creative. As they say, necessity is the mother of all invention. Nothing evolves to die; everything evolves to survive. I have no doubt that humanity will find creative ways to evolve.

In the end, maybe the only work to be done is on ourselves.

Footnotes:

- https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/jan/19/post-work-the-radical-idea-of-a-world-without-jobs

- https://workfutures.org/post/183267438328/work-futures-daily-workism

- https://eskokilpi.wordpress.com/2011/11/13/task-based-work-revisited/

- https://workfutures.substack.com/p/esko-kilpi-on-the-architecture-of-work

- https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/07/world-without-work/395294/

- https://www.mnn.com/green-tech/gadgets-electronics/blogs/what-will-we-all-do-post-work-society

- https://www.vouchercloud.com/resources/office-worker-productivity

- https://aeon.co/ideas/if-work-dominated-your-every-moment-would-life-be-worth-living

- https://qz.com/work/1272033/why-you-never-have-enough-time-a-history/

- https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Idleness-aversion-and-the-need-for-justifiable-Hsee-Yang/5c7b6b8f29702b7f9b90fe0436cec66b30c2b37f

- https://www.brainpickings.org/2015/08/10/leisure-the-basis-of-culture-josef-pieper/

- https://news.gallup.com/poll/241649/employee-engagement-rise.aspx