Siddhartha is to spiritual growth what The Alchemist is to life purpose.

While both purpose and spirituality have been life-transforming journeys for me, I was underwhelmed by The Alchemist (book summary) but thoroughly enjoyed the story of Siddhartha (Amazon).

The true profession of man is to find his way himself.

— Hermann Hesse

If you intend to read Siddhartha, the first thing to do is pick a translation. I always do a little research and read some reviews to try to pick the best translation (even though “best” is highly subjective).

I landed on the translation by Susan Bernofsky after seeing a bunch of praise for it.

Quick Housekeeping:

- All quotes are from the author unless otherwise stated.

- I’ve added emphasis (in bold) to quotes throughout this post.

- This summary is organized by Siddhartha’s spiritual journey stages that I’ve identified (not necessarily by the author’s chapters).

I’ve highlighted stage summaries in this color.

I’ve highlighted key aha moments within each stage in this color.

Summary Contents: Click a link to jump to a section below

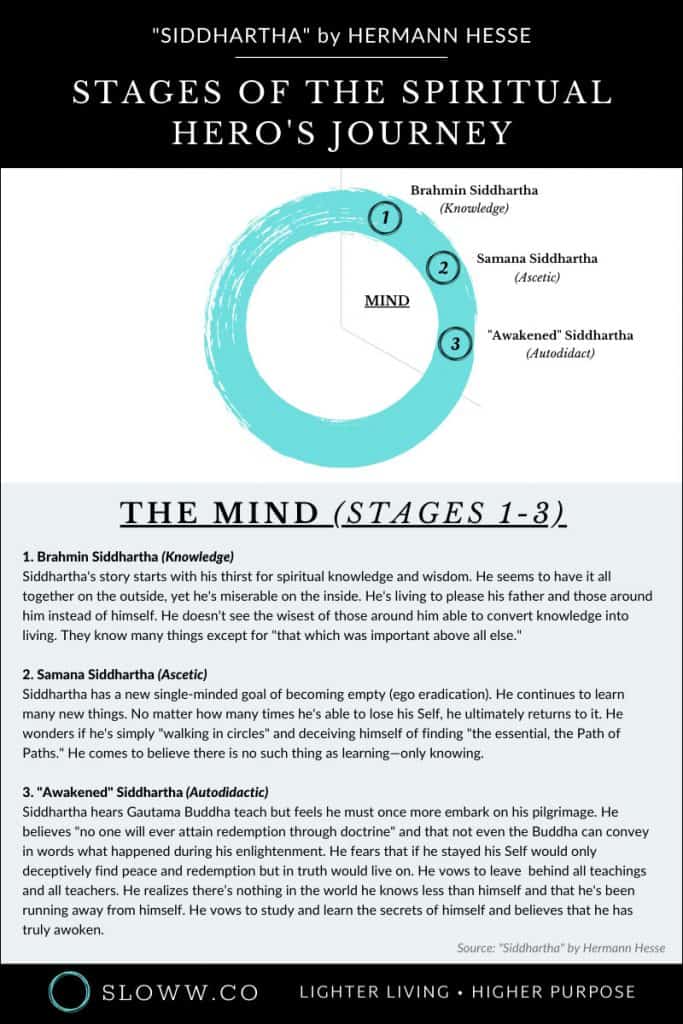

The Stages of Siddhartha’s Spiritual Hero’s Journey

- 1. Brahmin Siddhartha (Knowledge)

- 2. Samana Siddhartha (Ascetic)

- 3. “Awakened” Siddhartha (Autodidact)

- 7. Ferryman Siddhartha (Listening)

- 8. Father Siddhartha (Love)

- 9. Enlightened Siddhartha (Transcendence)

The Spiritual Hero’s Journey of a Lifetime: Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse (Book Summary)

About Hermann Hesse

- “Having vowed ‘to be a poet or nothing at all,’ the headstrong youth fled the seminary in Maulbronn at the age of fourteen. Thereafter Hesse rebelled against all attempts at formal schooling. Instead he pursued a rigorous program of self-study that focused on literature, philosophy, and history and eventually found employment at the Heckenhauer Bookshop in the university town of Tübingen.”

- “Chronic wanderlust coupled with growing discontent over his bucolic Rousseau-like existence took him on a formative trip to the East Indies in 1911.”

- “The publication of Demian that same year (it appeared in English in 1923) brought Hesse immediate acclaim throughout Europe. Based on his experience with Jungian analysis, this breakthrough novel launched a series of works chronicling the Weg nach Innen (inward journey) that he hoped would lead to self-knowledge. In the existential tradition of Nietzsche and Dostoevsky, Hesse portrays the turmoil of a docile young man who is forced to question traditional bourgeois beliefs regarding family, society, and faith.”

- “Hesse’s call for self-realization coupled with his celebration of Eastern mysticism earned him a huge following among America’s counterculture in the decade after his death.”

- “Hesse ‘is deeply loved by those among the American young who are questing,’ wrote Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.”

Almost all the prose works I have written are biographies of the soul…monologues in which a single individual is observed in relation to the world and to his own ego.

— Hermann Hesse

About Siddhartha (Introduction by Tom Robbins)

- “The problem, for writers and readers alike, with all this inward gazing is how few of us ever gaze in far enough to justify the strain. To reap lasting rewards, to escape the briar patch of perpetuated trauma, the gazer must delve beneath the ego level, the personality level, the level of genetic predisposition and environmental conditioning, must penetrate more deeply even than the archetypal underworld.”

- “Gradually he (Hesse) had come to recognize that very often despair, misery, and degeneration are simply the price we’re charged for our bad attitudes and myopic vision. Once he became convinced that we humans can alter reality by altering our perceptions of it, the lid was off the pitcher. Hesse went to his writing desk and poured the nectar.”

- “Like the existentialists, Hesse seemed to view the mass of humanity as one big twitchy, squealy, many-headed beast caught in a trap of its own making. Unlike Camus and Sartre, however, he suspected the trap might be sprung through a kind of alchemical transformation and/or spiritual transcendence.”

- “Siddhartha turns orthodox Hinduism inside out, flicks the translucent lint from Buddha’s much-contemplated navel, and deserts the extremist samanas with whom he’s been starving himself in the forest; becoming increasingly convinced that ‘a true seeker could not accept doctrine.’ Finally, the seeker even rejects seeking, concluding that ultimate reality can never be captured in a net made of thought, and that ‘knowing has no worse enemy than the desire to know.’ Strong stuff.”

- “The road to enlightenment is an unpaved road, closed to public transportation. It is because we must travel its last miles unencumbered and alone that Hesse has his traveler remind us emphatically that ‘Wisdom cannot be passed on.’ And that reminder may be the hardest, most valuable jewel in this literary lotus.”

Siddhartha learned new things with every step along his path, for the world was transformed and his heart was enchanted.

— Hermann Hesse

The Stages of Siddhartha’s Spiritual Hero’s Journey

The Mind (Stages 1-3)

1. Brahmin Siddhartha (Knowledge)

Stage Summary: Siddhartha’s story starts with his thirst for spiritual knowledge and wisdom. He seems to have it all together on the outside, yet he’s miserable on the inside. He’s living to please his father and those around him instead of himself. He doesn’t see the wisest of those around him able to convert knowledge into living. They know many things except for “that which was important above all else.”

- “Siddhartha had long since begun to join in the wise men’s counsels, to practice with Govinda the art of wrestling with words, to practice with Govinda the art of contemplation, the duty of meditation. He had mastered Om, the Word of Words, learned to speak it soundlessly into himself while drawing a breath, to speak it out soundlessly as his breath was released, his soul collected, brow shining with his mind’s clear thought. He had learned to feel Atman’s presence at the core of his being, inextinguishable, one with the universe.”

- “Joy leaped into his father’s heart at the thought of his son, this studious boy with his thirst for knowledge; he envisioned him growing up to be a great wise man and priest, a prince among Brahmins.“

- “Thus was Siddhartha beloved by all. He brought them all joy, filled them with delight. To himself, though, Siddhartha brought no joy, gave no delight.“

- “He had begun to suspect that his venerable father and his other teachers, all wise Brahmins, had already given him the richest and best part of their wisdom, had already poured their plenty into his waiting vessel, yet the vessel was not full: His mind was not content, his soul not at peace, his heart restless.”

Aha Moment: “They knew everything, these Brahmins and their holy books, everything, and they had applied themselves to everything, more than everything: to the creation of the world, the origins of speech, of food, of inhalation and exhalation; to the orders of the senses, the deeds of the gods—they knew infinitely many things—but was there value in knowing all these things without knowing the One, the Only thing, that which was important above all else, that was, indeed, the sole matter of importance?“

- “But where were the Brahmins, where the priests, where the wise men or penitents who had succeeded not merely in knowing this knowledge but in living it? Where was the master who had been able to transport his own being-at-home-in-Atman from sleep to the waking realm, to life, to all his comings and goings, his every word and deed?“

- “Said Siddhartha, ‘With your permission, my father. I have come to tell you that it is my wish to leave your house tomorrow and join the ascetics. I must become a Samana. May my father not be opposed to my wish.'”

- “‘You will go,’ he said. ‘Go to the forest and be a Samana. If you find bliss in the forest, come and teach it to me. If you find disappointment, return to me and we will once more sacrifice to the gods side by side.'”

2. Samana Siddhartha (Ascetic)

Stage Summary: Siddhartha has a new single-minded goal of becoming empty (ego eradication). He continues to learn many new things. No matter how many times he’s able to lose his Self, he ultimately returns to it. He wonders if he’s simply “walking in circles” and deceiving himself of finding “the essential, the Path of Paths.” He comes to believe there is no such thing as learning—only knowing.

- “Before him, Siddhartha saw a single goal: to become empty, empty of thirst, empty of want, empty of dream, empty of joy and sorrow. To let the ego perish, to be ‘I’ no longer, to find peace with an empty heart and await the miraculous with thoughts free of Self.“

- “Siddhartha learned many things from the Samanas; he learned to walk many paths leading away from the Self. He walked the path of eradication of ego through pain, through the voluntary suffering and overcoming of pain, of hunger, of thirst, of weariness. He walked the path of eradication of ego through meditation, using thought to empty the mind of all its notions.”

- “A thousand times he left his Self behind, spent hours and days at a time liberated from it. But just as all these paths led away from the Self, the end of each of them returned him to it.“

- “‘And now, Govinda, do you think we are on the right path? Are we drawing closer to knowledge? Are we drawing closer to redemption? Or are we not perhaps walking in circles—we who had hoped to escape the cycle?‘ Govinda replied, ‘We have learned much, Siddhartha, and much remains to be learned. We are not walking in a circle, we are ascending; the circle is a spiral, and we have already climbed many of its steps.'”

- “O Govinda, it seems to me that of all the Samanas that exist, there is perhaps not one, not a single one, who will reach Nirvana. We find consolations, we find numbness, we learn skills with which to deceive ourselves. But the essential, the Path of Paths, this we do not find.“

Aha Moment: “It has taken me long to learn this, Govinda, and still I am not quite done learning it: that nothing can be learned! There is in fact—and this I believe—no such thing as what we call ‘learning.’ There is, my friend, only knowing, and this is everywhere; it is Atman, it is in me and in you and in every creature. And so I am beginning to believe that this knowing has no worse enemy than the desire to know, than learning itself.“

- “One day when the two youths had lived among the Samanas for nearly three years and shared their exercises, word reached them in a roundabout way, a rumor, a legend: A man had been discovered, by the name of Gautama, the Sublime One, the Buddha, who had overcome the sufferings of the world within himself and brought the wheel of rebirths to a halt.”

- “How sweet it sounded, this legend of the Buddha; enchantment wafted from the reports. The world, after all, was diseased, life difficult to bear, and lo! Here was a new spring bubbling up, a messenger’s cry ringing out, consoling and mild, full of noble promises.“

- “I have become distrustful and weary of doctrines and learning and that I have little faith in words that come to us from teachers. But be that as it may, dear friend, I am prepared to hear these teachings, though in my heart I believe we have already tasted their finest fruit.”

3. “Awakened” Siddhartha (Autodidactic)

Stage Summary: Siddhartha hears Gautama Buddha teach but feels he must once more embark on his pilgrimage. He believes “no one will ever attain redemption through doctrine” and that not even the Buddha can convey in words what happened during his enlightenment. He fears that if he stayed his Self would only deceptively find peace and redemption but in truth would live on. He vows to leave behind all teachings and all teachers. He realizes there’s nothing in the world he knows less than himself and that he’s been running away from himself. He vows to study and learn the secrets of himself and believes that he has truly awoken.

- “Thus did Gautama stroll toward the town to collect alms, and the two Samanas recognized him solely by his perfect calm, the stillness of his figure, in which there was no searching, no desire, no imitation, no effort to be discerned, only light and peace.“

- “Gautama preached the doctrine of suffering, of the origins of suffering, of the path to the cessation of suffering. His words flowed quiet and clear. Suffering was life, the world was full of sorrow, but redemption from sorrow had been found: He who trod the path of the Buddha would find redemption.”

- “Said Siddhartha, ‘Yesterday, O Sublime One, I had the privilege of hearing your marvelous teachings. Together with my friend I came from far away to hear this doctrine. And now my friend will remain among your followers; he has taken refuge in you, while I am once more embarking on my pilgrimage.'”

- “You have heard my teachings, O Brahmin’s son, and it is well for you that you have thought so deeply about them. You have found a gap in them, an error. May you continue to contemplate it. But allow me to warn you, O inquisitive one, about the thicket of opinions and quibbling over words. Opinions are of little account; be they lovely or displeasing, clever or foolish, anyone can subscribe to or dismiss them. But the doctrine you heard from me is not my opinion, and its goal is not to explain the world to the inquisitive. It has a different goal; its goal is redemption from suffering. It is this redemption Gautama teaches, nothing else.“

Aha Moment: “Never for a moment have I doubted you. I never doubted for a moment that you are the Buddha, that you have reached the goal, the highest goal, toward which so many thousands of Brahmins and Brahmins’ sons are striving. You have found redemption from death. It came to you as you were engaged in a search of your own, upon a path of your own; it came to you through thinking, through meditation, through knowledge, through enlightenment. Not through doctrine did it come to you. And this is my thought, O Sublime One: No one will ever attain redemption through doctrine! Never, O Venerable One, will you be able to convey in words and show and say through your teachings what happened to you in the hour of your enlightenment. Much is contained in the doctrine of the enlightened Buddha; many are taught by it to live in an upright way, to shun evil. But there is one thing this so clear and venerable doctrine does not contain: It does not contain the secret of what the Sublime One himself experienced, he alone among the hundreds of thousands. This is what I thought and realized when I heard the doctrine. This is why I am continuing my journey—not in order to seek a different, better doctrine, for I know there is none, but to leave behind me all teachings and all teachers and to reach my goal alone or perish. But often will I remember this day, O Sublime One, and this hour when my eyes beheld a holy man.”

- “It is not fitting for me to pass judgment on another’s life! Only for myself, for myself alone, must I judge, must I choose, must I reject. Redemption from Self is what we Samanas seek, O Sublime One. If I were one of your disciples, O Venerable One, what I fear might happen is that my Self would only apparently, deceptively find peace and be redeemed, but that in truth it would live on and become huge, for I would have made the doctrine and my adherence to it and my love for you and the fellowship of the monks my Self!“

- “Something that had accompanied him throughout his youth and been a part of him was no longer present: the desire to have teachers and hear doctrine. He had left behind the last teacher to appear to him on his path, this highest and wisest of teachers, the holiest one, Buddha; he’d had to part even from him, unable to accept his doctrine.”

- “Thinking, he walked ever more slowly and asked himself, What is it now that you were hoping to learn from doctrines and teachers, and what is it that they—who taught you so much—were unable to teach you? And, he decided, It was the Self whose meaning and nature I wished to learn. It was the Self I wished to escape from, wished to overcome. But I was unable to overcome it, I could only trick it, could only run away from it and hide. Truly, not a single thing in all the world has so occupied my thoughts as this Self of mine, this riddle: that I am alive and that I am One, am different and separate from all others, that I am Siddhartha! And there is not a thing in the world about which I know less than about myself, about Siddhartha!“

Aha Moment: “That I know nothing of myself, that Siddhartha has remained such a stranger to me, such an unknown, comes from one cause, from a single cause: I was afraid of myself, was running away from myself! I was searching for Atman, searching for Brahman; I was prepared to chop my ego into little pieces and peel off its layers so as to find, in its unknown innermost core, the kernel that lies at the heart of every husk: Atman, Life, the Divine, that final utmost thing. But I myself got lost in the process.“

- “I won’t let my life and my thought begin with Atman and the world’s sorrows. No more killing myself, no more chopping myself into bits in the hope of finding some secret hidden among the debris. I will no longer follow Yoga-Veda, or Atharva-Veda, or the ascetics, or any other doctrine. I’ll be my own teacher, my own pupil. I’ll study myself, learn the secret that is Siddhartha.“

- “Everything was beautiful, everything mysterious and magical, and in the midst of all this was he, Siddhartha, in the moment of his awakening, on the path to himself.“

- “Meaning and being did not lie somewhere behind things; they lay within them, within everything.“

- “When a person reads something and wishes to grasp its meaning, he does not scorn the characters and letters and call them illusory, random, and worthless husks; he reads them, studies them, and loves them, letter for letter. But I—I who set out to read the book of the world and the book of my own being—I scorned the characters and letters in deference to a meaning I assumed in advance, I called the world of appearances illusory, called my own eye and my own tongue random and worthless illusions. Enough of all this. I have awoken, have truly awoken, and this day is the day of my birth.“

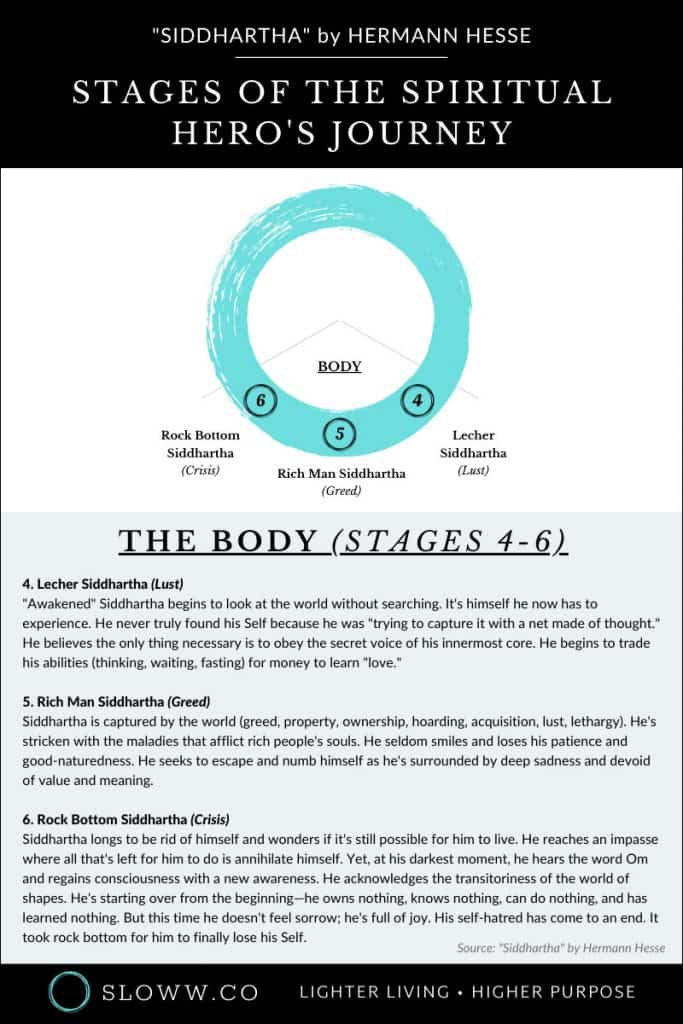

The Body (Stages 4-6)

4. Lecher Siddhartha (Lust)

Stage Summary: “Awakened” Siddhartha begins to look at the world without searching. It’s himself he now has to experience. He never truly found his Self because he was “trying to capture it with a net made of thought.” He believes the only thing necessary is to obey the secret voice of his innermost core. He begins to trade his abilities (thinking, waiting, fasting) for money to learn “love.”

- “But now his liberated eye dwelled in this realm, saw and recognized the visible, and was searching for a home in this world; no longer was it in search of Being, no longer were its efforts directed toward the Beyond. How beautiful the world was when one looked at it without searching, just looked, simply and innocently.“

- “How beautiful, how lovely it was to walk through the world like this, like a child, so awake, so open to what was near at hand, so free of distrust.”

- “All these things had always been there, and yet he had not seen them; he had not been present. Now he was present, he belonged.”

Aha Moment: “It was he himself he now had to experience. To be sure, he had known for a long time that his Self was Atman, of the same eternal essence as Brahman. But never had he truly found this Self, for he had been trying to capture it with a net made of thought. While certainly body was not Self—nor was it the play of the senses—this Self was also not thought, was not mind, was not the wisdom amassed through learning, not the learned art of drawing conclusions and spinning new thoughts out of old. No, even thought was still in this world; no goal could be reached by killing off the happenstance Self of the senses while continuing to fatten the happenstance Self of thought and learnedness. Thought and senses were both fine things. Ultimate meaning lay hidden behind them; both should be listened to, played with, neither scorned nor overvalued, for in each of them the secret voice of the innermost core might be discerned. He would aspire to nothing but what this voice commanded him, occupy himself with nothing but what the voice advised.“

- “To obey like this, to obey not a command from the outside but only the voice, to be in readiness—this was good, this was necessary. Nothing else was necessary.“

- (Kamala) “Friend, that is something many would like to know. You must do what you have learned to do and in exchange have people give you money and clothes and shoes. There is no other way for a poor man to get money. What do you know how to do?” (Siddhartha) “I can think. I can wait. I can fast.”

- “For a long time Kamala kissed him, and with deep astonishment Siddhartha felt how she was teaching him, how wise she was, how she mastered him, pushed him away, lured him, and how behind this first kiss stood a long, well-ordered, and well-tried sequence of kisses, each different from the others, still awaiting him. Breathing deeply, he stood there and in this moment was like a child, gaping in astonishment at the wealth of things worth knowing and learning that had opened before his eyes.”

- “Simple is the life one leads here in the world, Siddhartha thought. There are no difficulties. Everything was difficult, laborious, and in the end hopeless when I was still a Samana. Now everything is easy, easy as the kissing lessons Kamala is giving me. I need clothing and money, that is all. These goals are small and within reach; they will not trouble my sleep.”

- “You see, Kamala, when you throw a stone into the water, it hurries by the swiftest possible path to the bottom. It is like this when Siddhartha has a goal, a resolve. Siddhartha does nothing—he waits, he thinks, he fasts—but he passes through the things of this world like a stone through water, without doing anything, without moving; he is drawn and lets himself fall. His goal draws him to it, for he allows nothing into his soul that might conflict with this goal. This is what Siddhartha learned among the Samanas. It is what fools call magic and think is performed by demons. Nothing is performed by demons; there are no demons. Anyone can perform magic. Anyone can reach his goals if he can think, if he can wait, if he can fast.“

- “I lack possessions of my own free will, so this is not a hardship.”

- “Writing is good, thinking is better. Cleverness is good, patience is better.”

- “Each person gives what he has. The warrior gives strength, the merchant gives his goods, the teacher his doctrine, the farmer rice, the fisherman fish.” “Most certainly. And so what is it you have to give? What have you learned? What are your abilities?” “I can think. I can wait. I can fast.” “Is that all?” “I believe it is.”

- “Once he said to her, ‘You are like me; you are different from most people. You are Kamala, nothing else, and within you there is a stillness and a refuge into which you can withdraw at any moment and be at home within yourself, just as I can. Few people have this, and yet all people could have it.‘”

5. Rich Man Siddhartha (Greed)

Stage Summary: Siddhartha is captured by the world (greed, property, ownership, hoarding, acquisition, lust, lethargy). He’s stricken with the maladies that afflict rich people’s souls. He seldom smiles and loses his patience and good-naturedness. He seeks to escape and numb himself as he’s surrounded by deep sadness and devoid of value and meaning.

- “That noble, bright awakeness he had experienced once, at the height of his youth, in the days following Gautama’s sermon, after his parting from Govinda—that eager expectancy, that proud standing alone without teachers or doctrines, that supple readiness to hear the divine voice within his own heart—had gradually faded into memory; it had been transitory.”

- “To be sure, much of what he had learned—from the Samanas, from Gautama, from his father the Brahmin—had remained with him for a long time: moderate living, enjoyment of thought, hours devoted to samadhi, secret knowledge of the Self, that eternal being that is neither body nor consciousness. Much of this had remained with him, but one thing after another had settled to the bottom and been covered with dust. Just as a potter’s wheel, once set in motion, will continue to spin for a long time, only slowly wearying and coming to rest, so had the wheel of asceticism, the wheel of thought, and the wheel of differentiation gone on spinning for a long time in Siddhartha’s soul, and they were spinning still, but this spin was growing slow and hesitant; it was coming to a standstill. Slowly, as moisture seeps into the dying tree trunk, slowly filling it up and making it rot, worldliness and lethargy had crept into Siddhartha’s soul, filling it slowly, making it heavy, making it weary, putting it to sleep.”

- “His face was still more clever and spiritual than others, but it seldom smiled, and one after the other it was taking on the traits one so often observes in the faces of the wealthy: that look of dissatisfaction, infirmity, displeasure, lethargy, unkindness. Slowly he was being stricken with the maladies that afflict rich people’s souls.“

- “The world had captured him: voluptuousness, lust, lethargy, and in the end even greed, the vice he’d always thought the most foolish and had despised and scorned above all others. Property, ownership, and riches had captured him in the end. No longer were they just games to him, trifles; they had become chains and burdens.“

- “Siddhartha lost the composure with which he had once greeted losses, he lost his patience when others were tardy with their payments, lost his good-naturedness when beggars came to call, lost all desire to give gifts and loan money to supplicants.”

- “Whenever he was assailed by shame and nausea, he fled further, seeking to escape in more gambling, seeking to numb himself with sensuality and wine, and then hurled himself back into the grind of hoarding and acquisition. In this senseless cycle he ran himself ragged, ran himself old, ran himself sick.”

- “Waking from this dream with a start, he felt himself surrounded by deep sadness. Devoid of value, it seemed to him, devoid of value and meaning was this life he’d been living; nothing that was alive, nothing in any way precious or worthy of keeping, had remained in his hands. Alone he stood, and empty, like a shipwrecked man upon the shore.”

Aha Moment: “He had felt then, in his heart, ‘A path lies before you to which you are called; the gods are waiting for you.'”

- “‘Strive on! Strive on! You have a calling!’ He had heard this voice when he left home and chose the life of a Samana, he had heard it again when he left the Samanas to seek out the Perfect One, and again when he had left Gautama to venture into the Unknown. How long had it been since he had last heard that voice, how long since he had ascended to new heights.”

6. Rock Bottom Siddhartha (Crisis)

Stage Summary: Siddhartha longs to be rid of himself and wonders if it’s still possible for him to live. He reaches an impasse where all that’s left for him to do is annihilate himself. Yet, at his darkest moment, he hears the word Om and regains consciousness with a new awareness. He acknowledges the transitoriness of the world of shapes. He’s starting over from the beginning—he owns nothing, knows nothing, can do nothing, and has learned nothing. But this time he doesn’t feel sorrow; he’s full of joy. His self-hatred has come to an end. It took rock bottom for him to finally lose his Self.

- “Siddhartha wandered through the forest, already quite far from the city, knowing only this: He could never go back again. The life he had been living these many years was now over and done with.“

- “He longed to be rid of himself, to find peace, to be dead. If only a bolt of lightning would strike him down! If only a tiger would devour him! If only there were a wine, a poison, that would numb him, bring him oblivion and sleep, and no more awakenings!”

- “Was it still possible to live? Was it possible to continue, over and over again, to draw breath, to exhale, to feel hunger, to eat again, to sleep again, to lie again beside a woman? Had not this cycle been exhausted for him, concluded?”

- “What reason did he have to continue walking—walking where, and with what goal? No, there were no more goals; all that was left was a deep painful longing to shake off this whole mad dream, to spit out this stale wine, to put an end to this pitiful, shameful existence.“

- “He had reached an impasse. All that was left for him to do was annihilate himself, smash to pieces the botched structure of his life, throw it away, hurl it at the feet of the mocking gods.”

Aha Moment: “Then, from distant reaches of his soul, from bygone realms of his weary life, a sound fluttered. It was a word, a syllable that he now spoke aloud, mindlessly, his voice a babble, the first and final word of every Brahmin prayer, the holy Om that meant the perfect ox perfection. And the moment the sound Om touched Siddhartha’s ear, his slumbering spirit suddenly awoke and recognized the foolishness of his actions.”

- “He knew only that his former life—in his first moment of new awareness, this former life appeared to him like a previous incarnation from the distant past, an early embodiment of his present Self—his former life had been left behind, that he had even wanted to throw away his life in his nausea and misery, but that he had regained consciousness beneath a coconut palm with the holy word Om upon his lips; he had then fallen asleep, and now, having awoken, he beheld the world as a new man.”

- (Govinda) “‘Siddhartha, where are you going?’ Siddhartha said, ‘It is just the same with me as with you, my friend. I am going nowhere. I am merely journeying, I am on a pilgrimage.‘”

- “Remember, my friend: The world of shapes is transitory, and transitory—highly transitory—are our clothes, the way we wear our hair, and our hair and bodies themselves.”

- (Govinda) “And now, Siddhartha, what are you now?” (Siddhartha) “This I do not know. I have as little an idea as you do. I am on a journey. I was a rich man and am rich no longer, and what I will be tomorrow I do not know.”

- “Swiftly does the wheel of shapes turn, Govinda. Where is the Brahmin Siddhartha? Where is the Samana Siddhartha? Where is the rich man Siddhartha? The transitory changes swiftly, Govinda, as you know.”

- “This was precisely the form of the enchantment that the Om had wrought within him as he slept: He loved everything and was filled with joyous love for all he saw, and he realized that what had so ailed him before was that he had been able to love nothing and no one.“

- “With sorrow, yet also with laughter, he thought of this time. Back then, he recalled, he had boasted of three things before Kamala, the three noble and unassailable arts he had mastered: fasting—waiting—thinking. These had been his possessions, his power and strength, his sturdy staff; it was these three arts he had studied in the assiduous, laborious years of his youth, to the exclusion of all else. And now they had abandoned him; not one of them remained, not fasting, not waiting, not thinking. He had sacrificed them for the most miserable of things, the most transitory: for sensual pleasure, for luxury, for wealth!“

Aha Moment: “Now that all these utterly transitory things have slipped away from me, he thought, I am left under the sun just as I stood here once as a small child; I own nothing, know nothing, can do nothing, have learned nothing. How curious this is! Now that I am no longer young, now that my hair is already half gray and my strength is beginning to wane, I am starting over again from the beginning, from childhood! Again he had to smile. Yes, it certainly was strange, this fate of his! Things were going downhill with him, and now he was once more standing in the world, empty and naked and foolish. But he could not quite bring himself to feel sorrowful on this account. Indeed, he felt a tremendous urge to burst out laughing: laughter at himself, laughter at this strange, foolish world.”

- “Curious indeed this life of mine has been, he thought, it has taken such strange detours. As a boy I was concerned only with gods and sacrifices. As a youth I was concerned only with asceticism, with thinking and samadhi; I went searching for Brahman, revered the eternal in Atman. But as a young man I set off after the penitents, lived in the forest, suffered heat and frost, learned to go without food, taught my body to feel nothing. How glorious it was then when realization came to me in the doctrine of the great Buddha; I felt knowledge of the Oneness of the world coursing through me like my own blood. But even the Buddha and his great knowledge had to be left behind. I went off and learned the pleasures of love from Kamala, learned to conduct business from Kamaswami, accumulated money, squandered money, learned to love my stomach, learned to indulge my senses. I had to spend many years losing my spirit, unlearning how to think, forgetting the great Oneness. Is it not as if I were slowly and circuitously turning from a man into a child, from a thinker into one of the child people? And still this path has been very good, and still the bird in my breast has not died. But what a path it has been! I have had to pass through so much foolishness, so much vice, so much error, so much nausea and disillusionment and wretchedness, merely in order to become a child again and be able to start over. But all of this was just and proper; my heart is saying yes, and my eyes are laughing. I had to experience despair, I had to sink to the most foolish of all thoughts, the thought of suicide, to be able to experience grace, to hear Om again, to be able to sleep well and awaken well. I had to become a fool to find Atman within me once more. I had to sin to be able to live again. Where else may my path be taking me? How stupid it is, this path of mine; it goes in loops. For all I know it’s going in a circle. Let it lead where it will, I shall follow it.“

- “No, never again will I imagine, as I once enjoyed doing, that Siddhartha was a wise man! But one thing I did do well, one thing pleases me, which I must praise: All my self-hatred has now come to an end, along with that idiotic, desolate existence!”

- “He might have remained a great while longer at Kamaswami’s side, earning money, squandering money, stuffing his belly and letting his soul thirst; he might have gone on living a great while longer in this cozy well-upholstered hell if that moment had not come: that moment of utter despondency and despair, that extreme moment when he was hanging above the flowing water, ready to destroy himself. That he had felt this despair, this deepest nausea, and yet had not succumbed to it, that the bird, the happy fountainhead and voice within him, had remained alive after all—it was because of all these things that he now felt such joy, that he laughed, that his face was beaming beneath his gray hair.”

- “It is good, he thought, to taste for oneself all that it is necessary to know. Already as a child I learned that worldly desires and wealth were not good things. I have known this for a long time but have only now experienced it. And now I do know it, know it not only with my memory but with my eyes, with my heart, and with my stomach. How glad I am to know it!”

- “For a long time he contemplated his transformation, listening as the bird sang with joy. Had this bird not died within him, had he not felt its death? No, something else had died within him, something that had desired death for a long time. Was it not the very thing that he had once, in his ardent years as a penitent, wanted to kill? Was it not his Self, his nervous, proud little ego that he had done battle with for so many years, that had bested him again and again, that was always back again each time he killed it off, forbidding joy and feeling fear? Was it not this that had finally met its death today, here in the forest beside this lovely river? Was it not because of this death that he was now like a child, so full of trust, so devoid of fear, so full of joy?“

- “This is why he’d had to go on enduring these hateful years, enduring the nausea, the emptiness, the senselessness of a desolate, lost existence, enduring to the end, to the point of bitter despair, until even the lecher Siddhartha, the greedy Siddhartha, could die. He had died, and a new Siddhartha had awoken from sleep. He too would grow old; he too would have to die someday. Siddhartha was transitory, every shape was transitory. Today, though, he was young; he was a child, the new Siddhartha, and was full of joy.“

- “It seemed to him that the river had something special to say to him, something he did not yet know, something still awaiting him. In this river Siddhartha had wished to drown, and in it the old, weary, despairing Siddhartha did indeed drown this day. The new Siddhartha, however, felt a deep love for this flowing water and resolved not to leave it again so soon.“

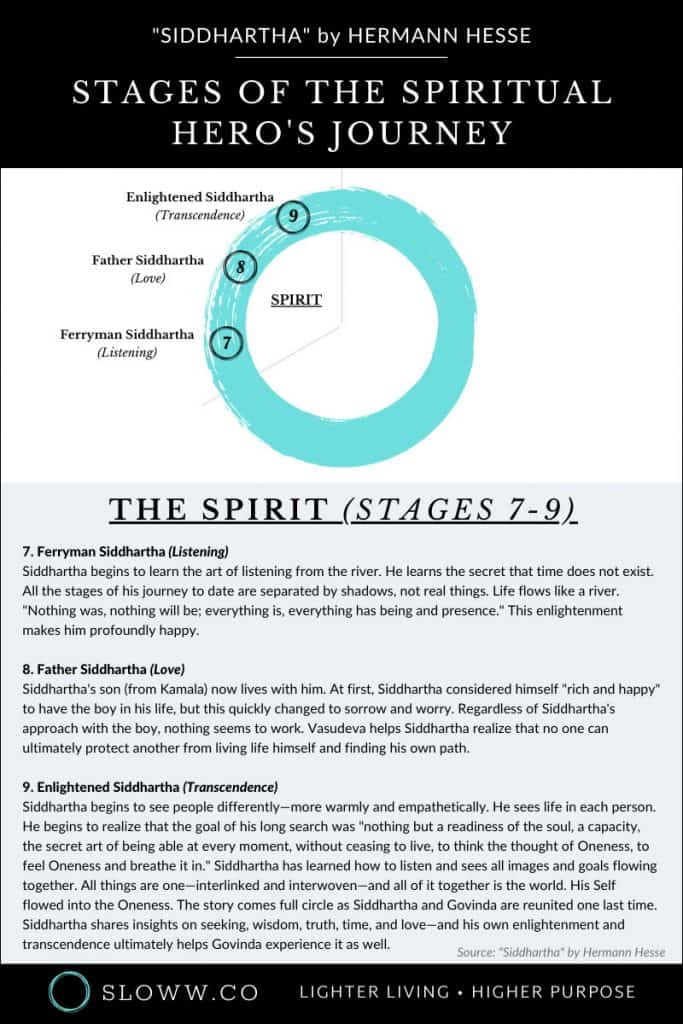

The Spirit (Stages 7-9)

7. Ferryman Siddhartha (Listening)

Stage Summary: Siddhartha begins to learn the art of listening from the river. He learns the secret that time does not exist. All the stages of his journey to date are separated by shadows, not real things. Life flows like a river. “Nothing was, nothing will be; everything is, everything has being and presence.” This enlightenment makes him profoundly happy.

- “But of all the water’s secrets, he saw today only a single one—one that struck his soul. He saw that this water flowed and flowed, it was constantly flowing, and yet it was always there; it was always eternally the same and yet new at every moment! Oh, to be able to grasp this, to understand it! He did not understand it, did not grasp it; he felt only an inkling stirring within him, distant memory, divine voices.”

- (Vasudeva) “Is not every life, every work, lovely?”

- “This was one of the greatest among the ferryman’s virtues: He had mastered the art of listening.“

- “Rare are those who know how to listen; never before have I met anyone who was as skilled in listening as you are. This too I shall learn from you.”

- “‘You will learn this,’ Vasudeva said, ‘but not from me. It was the river that taught me to listen, and it will teach you as well. It knows everything, the river, and one can learn anything from it. You too, after all, have already learned from the river that it is good to strive for downward motion, to sink, to seek the depths.”

- (Vasudeva) “There were a few among these thousands, just a few of them, four or five, for whom the river ceased to be an obstacle. They heard its voice, they listened to it, and the river became holy to them as it has become holy to me.”

- (Vasudeva) “I am not a learned man. I do not know how to speak, I do not even know how to think. I know only how to listen and to be pious; these are the only things I have learned.“

- “But even more than Vasudeva could teach him, he learned from the river, which taught him unceasingly. Above all, it taught him how to listen—how to listen with a quiet heart and a waiting, open soul, without passion, without desire, without judgment, without opinion.“

Aha Moment: “‘Have you too,’ he asked him once, ‘have you too learned this secret from the river: that time does not exist?‘”

- “Vasudeva’s face broke into a radiant smile. ‘Yes, Siddhartha,’ he said. ‘Is this what you mean: that the river is in all places at once, at its source and where it flows into the sea, at the waterfall, at the ferry, at the rapids, in the ocean, in the mountains, everywhere at once, so for the river there is only the present moment and not the shadow of a future?‘”

- “‘It is,’ Siddhartha said. ‘And once I learned this I considered my life, and it too was a river, and the boy Siddhartha was separated from the man Siddhartha and the graybeard Siddhartha only by shadows, not by real things. Siddhartha’s previous lives were also not the past, and his death and his return to Brahman not the future. Nothing was, nothing will be; everything is, everything has being and presence.‘”

- “Siddhartha spoke with rapture; this enlightenment had made him profoundly happy. Oh, was not then all suffering time, was not all self-torment and fear time, did not everything difficult, everything hostile in the world vanish, was it not overcome as soon as one had overcome time, as soon as one could think it out of existence?“

- “Often they sat together in the evenings beside the riverbank on the tree trunk, sat in silence, both listening to the water, which for them was not water but rather the voice of Life, the voice of Being, of the eternally Becoming.“

- “A long time ago he had realized there was no longer anything separating him from Gautama, whose doctrine he had been unable to accept. No, a true seeker could not accept doctrine, not a seeker who truly wished to find. But the one who had found what he was seeking could give his approval to any teaching, any discipline at all, to any path, any goal—there was no longer anything separating him from the thousand others who were living in the Eternal and breathing the Divine.”

8. Father Siddhartha (Love)

Stage Summary: Siddhartha’s son (from Kamala) now lives with him. At first, Siddhartha considered himself “rich and happy” to have the boy in his life, but this quickly changed to sorrow and worry. Regardless of Siddhartha’s approach with the boy, nothing seems to work. Vasudeva helps Siddhartha realize that no one can ultimately protect another from living life himself and finding his own path.

- “Rich and happy is what he’d called himself when the boy had come to him. But when with the passing of time the boy remained a sullen stranger, when he displayed a proud and stubborn heart, refused to work, showed no reverence for his elders, and plundered Vasudeva’s fruit trees, Siddhartha began to understand that it was not happiness and peace that had come to him with his son but, rather, sorrow and worry. But he loved him and preferred the sorrow and worry of love to the happiness and peace he had known without the boy.”

- (Vasudeva) “Water seeks out water; youth seeks out youth. Your son is not in a place where he can flourish. Ask the river and hear its counsel for yourself!”

- “‘Could I bring myself to part with him?’ he asked quietly, ashamed. ‘Give me more time, my friend! I am fighting for him, you see, trying to win his heart and hoping to capture it with loving-kindness and patience. To him too the river must speak someday; he too has a calling.'”

- “Vasudeva’s smile blossomed more warmly. ‘Indeed, he too has a calling; he too will enjoy eternal life. But do we know, you and I, to what he has been called: to what path, to what deeds, to what sufferings? His sorrows will not be slight, for his heart is proud and hard; those like him must suffer a great deal, commit many errors, do much wrong, pile much sin upon themselves. Tell me, my friend, are you educating your son? Do you force him? Do you strike him? Do you punish him?’ ‘No, Vasudeva, I do none of these things.’ ‘This I knew. You do not force him, do not strike him, do not command him because you know that soft is stronger than hard, water stronger than rock, love stronger than violence. Very good, I praise you. But is it not an error for you to think that you are not forcing him, not punishing him? Do you not bind him with the bands of your love? Do you not shame him daily and make things more difficult for him with your kindness and patience? Are you not forcing him, the arrogant and spoiled boy, to live in a hut with two old banana eaters for whom even rice is a delicacy, whose thoughts cannot be his, whose hearts are old and still and beat differently from his? Do all these things not force him, punish him?‘”

Aha Moment: (Vasudeva) “My friend, have you entirely forgotten that instructive story about Siddhartha, the Brahmin’s son, that you once related to me here in this very spot? Who saved the Samana Siddhartha from Sansara, from sin, from greed, from folly? Were his father’s piety, his teachers’ admonitions, his own knowledge, and his own searching able to protect him? What father, what teacher, was able to protect him from living life himself, soiling himself with life, accumulating guilt, drinking the bitter drink, finding his own path? Do you think then, my friend, that this path might be spared anyone at all? Perhaps your little son, because you love him and would like to spare him sorrow and pain and disillusionment? But even if you died ten times for him, you would not succeed in relieving him of even the smallest fraction of his destiny.”

- “He could sense quite distinctly that this blind love for his son was a passion, something very human, that it was Sansara, a muddy spring, dark water. Yet at the same time he felt that it was not without value—it was necessary, it came out of his own being. This too was pleasure that had to be atoned for; this too, pain to be experienced; these too, follies to be committed.”

9. Enlightened Siddhartha (Transcendence)

Stage Summary: Siddhartha begins to see people differently—more warmly and empathetically. He sees life in each person. He begins to realize that the goal of his long search was “nothing but a readiness of the soul, a capacity, the secret art of being able at every moment, without ceasing to live, to think the thought of Oneness, to feel Oneness and breathe it in.” Siddhartha has learned how to listen and sees all images and goals flowing together. All things are one—interlinked and interwoven—and all of it together is the world. His Self flowed into the Oneness. The story comes full circle as Siddhartha and Govinda are reunited one last time. Siddhartha shares insights on seeking, wisdom, truth, time, and love—and his own enlightenment and transcendence ultimately helps Govinda experience it as well.

- “He now saw people differently than he had before, less cleverly, less proudly, but more warmly, with more curiosity and empathy.“

- “Although he had nearly reached perfection and still felt the pangs of his recent wound, it seemed to him as if these child people were his brothers. Their vanities, desires, and ridiculous habits were losing their ridiculousness for him; they were becoming comprehensible, lovable, even worthy of respect.“

- “All these drives, all these childish matters, all these simple, foolish, but enormously strong, strongly alive, strongly asserted drives and desires were no longer mere child’s play to Siddhartha; he saw people living for their sake, saw them performing endless feats for their sake—making journeys, waging wars, suffering endless sufferings, enduring endless burdens—and he was able to love them for this; he saw life, the living, the indestructible, the Brahman in each of their passions, each of their deeds. Lovable and admirable these people were in their blind fidelity, their blind strength and tenacity. They were lacking in almost nothing; the one thing possessed by the thinker, the man of knowledge, that they lacked was only a trifle, one small thing: consciousness, conscious thought of the Oneness of all things. And at times Siddhartha even doubted whether this knowledge, this thinking, should be so highly valued, wondered whether it too was not perhaps the child’s play of thought people, who might be the child people of thought. In all other matters, the worldly were the wise man’s equals, were in fact far superior to him in many ways, just as animals, in their tenacious, unerring performance of what is necessary, can appear superior to people at certain moments.”

Aha Moment (on Oneness): “Slowly blossoming, slowly ripening within Siddhartha, was the realization and knowledge of what wisdom and the goal of his long search really was. It was nothing but a readiness of the soul, a capacity, the secret art of being able at every moment, without ceasing to live, to think the thought of Oneness, to feel Oneness and breathe it in. Slowly this was blossoming within him, shining out at him from Vasudeva’s aged childish face: harmony, knowledge of the eternal perfection of the world, smiling, Oneness.“

- “Had not his father suffered the same pain he himself was now suffering on account of his son? Had not his father died long ago, without ever having seen his son again? Must not he himself expect the same fate? Was not this repetition a comedy, a strange and foolish thing, this constant circulation in a preordained course?”

- “As he continued to speak, continued to confess and recount, Siddhartha felt more and more strongly that it was no longer Vasudeva listening to him, no longer a human being, that this motionless listener was drinking in his confession as a tree drinks in rain, that this motionless one was the river, God, the Eternal itself. And as Siddhartha ceased to think of himself and his wound, his recognition of the changed essence of Vasudeva took possession of him; the more deeply he felt it and entered into it, the less strange it became and the more he realized that all this was as it should be and natural, that Vasudeva had been this way a long time, nearly always; it was just that he himself had not quite recognized it, and that in fact he himself was scarcely different from Vasudeva any longer.“

- “Siddhartha made an effort to listen better. The image of his father, his own image, and the image of his son all flowed together; Kamala’s image also appeared and dissolved, and the image of Govinda, and other images; they all flowed together. All became the river, all of them striving as river to reach their goal, longingly, eagerly, suffering, and the river’s voice rang out full of longing, full of burning sorrow, full of unquenchable desire. The river strove to its goal; Siddhartha saw it hurrying along, the river that was made of himself and those he loved and all the people he had ever seen; all the waves and waters were hurrying, suffering, toward goals, many goals—the waterfall, the lake, the rapids, the sea—and all these goals were reached, and each of them was followed by a new goal, and the water turned to steam and rose into the sky; it became rain and plunged down from the heavens; it became a spring, became a brook, became a river, striving anew, flowing anew. But the longing voice had changed. It still rang out, sorrowfully, searchingly, but other voices now joined it, voices of joy and of sorrow, good and wicked voices, laughing and mourning, a hundred voices, a thousand.”

- “Siddhartha listened. He was now completely and utterly immersed in his listening, utterly empty, utterly receptive; he felt he had now succeeded in learning how to listen. He had heard all these things often now, these many voices in the river; today it sounded new. Already he could no longer distinguish the many voices, could not distinguish the gay from the weeping, the childish from the virile; they all belonged together, the yearning laments and the wise man’s laughter, the cry of anger and the moans of the dying; they were all one, all of them interlinked and interwoven, bound together in a thousand ways. And all of this together—all the voices, all the goals, all the longing, all the suffering, all the pleasure, everything good and everything bad—all of it together was the world. All of it together was the river of occurrences, the music of life. And when Siddhartha listened attentively to this river, to this thousand-voiced song, when he listened neither for the sorrow nor for the laughter, when he did not attach his soul to any one voice and enter into it with his ego but rather heard all of them, heard the whole, the oneness—then the great song of the thousand voices consisted only of a single word: Om, perfection.“

Aha Moment (on non-resistance): “His wound blossomed; his sorrow shone; his Self had flowed into the Oneness. In this hour Siddhartha ceased to do battle with fate, ceased to suffer. Upon his face blossomed the gaiety of knowledge that is no longer opposed by any will, that knows perfection, that is in agreement with the river of occurrences, with the current of life, full of empathy, full of fellow feeling, given over to the current, part of the Oneness.“

Aha Moment (on seeking): “‘When a person seeks,’ Siddhartha said, ‘it can easily happen that his eye sees only the thing he is seeking; he is incapable of finding anything, of allowing anything to enter into him, because he is always thinking only of what he is looking for, because he has a goal, because he is possessed by his goal. Seeking means having a goal. Finding means being free, being open, having no goal. You, Venerable One, are perhaps indeed a seeker, for, striving to reach your goal, you overlook many things that lie close before your eyes.'”

- “Some people, Govinda, have to change a great deal, have to wear all sorts of garments, and I am one of these, my dear friend.”

- “As you know, my dear friend, I began to distrust doctrines and teachers already as a young man, in the days when we were living among the penitents in the forest, and I turned my back on them. I have stuck to this. Nonetheless I have had many teachers since then...Most of all, however, I learned here, from this river, and from my predecessor, the ferryman Vasudeva. He was a very simple man, Vasudeva. He was not a thinker, but he knew what is necessary to know; just as much as Gautama he was a Perfect One, a saint.”

Aha Moment (on wisdom): “There were several thoughts, but it would be difficult for me to hand them on to you. You see, my Govinda, here is one of the thoughts I have found: Wisdom cannot be passed on. Wisdom that a wise man attempts to pass on always sounds like foolishness...One can pass on knowledge but not wisdom. One can find wisdom, one can live it, one can be supported by it, one can work wonders with it, but one cannot speak it or teach it.”

Aha Moment (on truth): “The opposite of every truth is just as true! For this is so: A truth can always only be uttered and cloaked in words when it is one-sided. Everything is one-sided that can be thought in thoughts and said with words, everything one-sided, everything half, everything is lacking wholeness, roundness, oneness. When the sublime Gautama spoke of the world in his doctrine, he had to divide it into Sansara and Nirvana, into illusion and truth, into suffering and redemption. This is the only way to go about it; there is no other way for a person who would teach. The world itself, however, the Being all around us and within us, is never one-sided. Never is a person, or a deed, purely Sansara or purely Nirvana, never is a person utterly holy or utterly sinful.”

Aha Moment (on time): “It only seems so because we are subject to the illusion that time exists as something real. Time is not real, Govinda. I have experienced this again and again. And if time is not real, then the distance that appears to lie between world and eternity, between suffering and bliss, between evil and good, is also an illusion.”

- “The sinner who I am and who you are is a sinner, but one day he will again be Brahman, he will one day reach Nirvana, will be a Buddha—and now behold: This one day is an illusion, it is only an allegory! The sinner is not on his way to the state of Buddhahood, he is not caught up in a process of developing, although our thought cannot imagine things in any other way. No, in this sinner the future Buddha already exists—now, today—all his future is already there. In him, in yourself, in everyone you must worship the future Buddha, the potential Buddha, the hidden Buddha. The world, friend Govinda, is not imperfect, nor is it in the middle of a long path to perfection. No, it is perfect in every moment; every sin already carries forgiveness within it, all little children already carry their aged forms within them, all infants death, all dying men eternal life. It is not possible for anyone to see how far any other person has come along his path. Buddha waits within the robber and the dice player, and the robber waits in the Brahmin.”

- “In the deepest meditation we have the possibility of negating time, of seeing all life, all having-been, being, and becoming, as simultaneous, and then everything is good, everything is perfect, everything is Brahman. Therefore everything that is appears good to me. Death appears to me like life, sin like holiness, cleverness like folly; everything must be just as it is, everything requires only my assent, only my willingness, my loving approval, and for me it is good and can never harm me. I experienced by observing my own body and my own soul that I sorely needed sin, sorely needed concupiscence, needed greed, vanity, and the most shameful despair to learn to stop resisting, to learn to love the world and stop comparing it to some world I only wished for and imagined, some sort of perfection I myself had dreamed up, but instead to let it be as it was and to love it and be happy to belong to it.”

Aha Moment (on words): “Words are not good for the secret meaning; everything always becomes a little bit different the moment one speaks it aloud, a bit falsified, a bit foolish—yes, and this too is also very good and pleases me greatly: that one person’s treasure and wisdom always sounds like foolishness to others.”

- “For the stone and the river, for all these things that we contemplate and from which we can learn, I feel love. I can love a stone, Govinda, and also a tree or a piece of bark. These are things and things can be loved. Words, however, I cannot love. This is why doctrines are not for me. They have no hardness, no softness, no colors, no edges, no smell, no taste; they have nothing but words. Perhaps it is this that has hindered you in finding peace; perhaps it is all these words. For even redemption and virtue, even Sansara and Nirvana, are just words, Govinda. There is no thing that could be Nirvana; there is only the word Nirvana.”

- “When this holy man (ferryman) went into the forest, he knew everything, knew more than you or I, without teachers, without books, only because he had believed in the river.”

Aha Moment (on love): “Love, O Govinda, appears to me more important than all other matters. To see through the world, to explain it, to scorn it—this may be the business of great thinkers. But what interests me is being able to love the world, not scorn it, not to hate it and hate myself, but to look at it and myself and all beings with love and admiration and reverence.”

- “Even with regard to him (Buddha), your great teacher, things are dearer to me than words, his actions and life more important than his speeches, the gestures of his hand more important than his opinions. It is not in his speaking or in his thinking that I see his greatness, only in his actions, his life.”

- “‘Bend down to me,’ he whispered softly in Govinda’s ear. ‘Bend down here to me! Yes, like that, closer! Even closer! Kiss me on the forehead, Govinda!’ When Govinda, perplexed and yet drawn by great love and foreboding, obeyed his words, bent down close to him, and touched his forehead with his lips, something wondrous happened to him. While his thoughts were still lingering over Siddhartha’s odd words, while he was still fruitlessly and reluctantly attempting to think away time, to imagine Nirvana and Sansara as one, while a certain contempt for his friend’s words was even then battling inside him with tremendous love and reverence, this happened: He no longer saw the face of his friend Siddhartha; instead he saw other faces, many of them, a long series, a flowing river of faces, by the hundreds, by the thousands, all of them coming and fading away, and yet all of them appearing to be there at once, all of them constantly changing, being renewed, and all of them at the same time Siddhartha…he saw all these figures and faces in their thousandfold interrelations, each helping the others, loving them, hating them, destroying them, giving birth to them anew; each one was a wanting-to-die, a passionately painful confession of transitoriness, and yet none of them died; each of them was only transformed, constantly born anew, constantly being given a new face, without time having passed between one face and the next—and all these figures and faces rested, flowed, engendered one another, floated off and streamed into and through one another, and constantly stretched over all of them was something thin, an insubstantial but nonetheless existing thing like thin glass or ice, like a transparent skin, a bowl or shape or mask made of water, and this mask was smiling, and this mask was Siddhartha’s smiling face, which he, Govinda, at just this moment was touching with his lips. And Govinda saw that this smiling of the mask, this smile of Oneness over all the flowing figures, this smile of simultaneousness over the thousand births and deaths, this smile of Siddhartha was precisely the same, was precisely the same still, delicate, impenetrable, perhaps kind, perhaps mocking, wise, thousandfold smile of Gautama, the Buddha, as he himself had seen it a hundred times with awe. This, Govinda knew, is how the Perfect Ones smiled. No longer knowing whether time existed, whether this looking had lasted a second or a hundred years, no longer knowing whether there was a Siddhartha, whether a Gautama, whether a Self, an I and You, wounded in his innermost core as if by a divine arrow whose wound tastes sweet, entranced and bewildered in his innermost core, Govinda remained standing there a short while longer, bending over Siddhartha’s still face that he had just kissed, that had just been the site of all shapes, all Becoming, all Being. This countenance appeared unchanged once the depths of the thousandfold immensity had closed again beneath its surface; he was silently smiling, smiling quietly and gently, very kindly perhaps, perhaps mockingly, precisely as he had smiled, the Sublime One. Deeply Govinda bowed, tears of which he knew nothing coursed down his old face, and like a fire the feeling of the most ardent love, the most humble reverence was burning in his heart. Deeply he bowed, bowed to the very earth, before the one sitting there motionless, whose smile reminded him of everything he had ever loved in all his life, everything that had ever, in all his life, been dear to him and holy.“

You May Also Enjoy:

- Top book summaries (or browse all book summaries)