This is a book summary of A Synthesizing Mind: A Memoir from the Creator of Multiple Intelligences Theory by Howard Gardner (Amazon).

Premium members have access to the companion post: 🔒How to be a Synthesizer with “A Synthesizing Mind” by Howard Gardner (+ Infographics)

🧠 UPDATE: The new Synthesizer course is now live!

While this book is technically a memoir, I’ve focused my notes in this summary specifically on what Gardner says about synthesis, synthesizing, and the synthesizing mind. For his life story—which is very interesting (especially his childhood)—you’ll have to read the book!

If you’re looking for an introduction to Howard Gardner, here’s a recent interview:

Quick Housekeeping:

- All quotes are from the author unless otherwise stated.

- Some quotes are paraphrased (shown without quotation marks).

- Everything is grouped by my own themes (not the author’s chapters).

- I’ve added my own emphasis throughout in bold.

Book Summary Contents: Click a link here to jump to a section below

- Introduction to the book

- What is Multiple Intelligences Theory (MI Theory)?

- The Five Minds

- What is the Synthesizing Mind?

- Do you have a Synthesizing Mind?

- A Continuum of Synthesis (Types & Mediums)

- Gardner’s Personal Synthesizing Process

A Look Inside A Synthesizing Mind by Howard Gardner (Book Summary)

“In the twenty-first century, the most important kind of mind will be the synthesizing mind.” — Murray Gell-Mann, Nobel Laureate in Physics in 1969, the founding genius behind the interdisciplinary Santa Fe Institute, and the coiner of the term “synthesizing mind”

Introduction to A Synthesizing Mind

“To get to the nub of the matter: I am convinced that my own mind is a synthesizing mind … In dissecting the act, or art, of synthesis, I believe that I can illuminate a kind of mind that has not been much analyzed and that may prove especially important in the chapter of human history that lies ahead.”

- “I try at last to look in the mirror and figure out the operation of my own synthesizing mind: where it came from, how it works, what is distinctive about it, and what lessons this self-knowledge might yield for other persons with other minds in this and other times.”

- “From the very beginning of my studies, I have been attracted to a certain approach to research and writing. Technically, one could call it ‘qualitative social science,’ but it’s more accurate, and less pretentious, to call this approach ‘works of synthesis’ about the human mind, human nature, and human culture.”

- “I think of myself as a lapsed psychologist, as a systematic social thinker, and above all, as I argue in the concluding chapters of this book, as a synthesizer of knowledge about human beings and the human mind. And then, for most of the rest of the world, I am an educator, or educationalist.”

What is Multiple Intelligences Theory (MI Theory)?

Defining what constitutes an intelligence: “A human intellectual competence must entail a set of skills of problem solving—enabling the individual to resolve genuine problems or difficulties that he or she encounters, and, when appropriate, to create an effective product—and must entail the potential for finding or creating problems—hereby laying the groundwork for the acquisition of new knowledge.”

Content is the heart of the matter. According to my analysis, we don’t process music in the same way as we process numerical or spatial or personal information. Nor does memory for one kind of content reliably predict memory for other kinds of content.

1. Linguistic intelligence:

- Ex: lawyer, poet, journalist, storyteller

2. Logical-mathematical intelligence:

- Ex: scientist, accountant, computer expert, trader, timekeeper

3. Musical intelligence:

- Ex: composer, singer, instrumentalist, chanter, improviser, devoted fan, or critic

4. Spatial intelligence:

- Ex: large-scale space (like a navigator, pilot); local space (chess player, mapmaker, sculptor)

5. Bodily kinesthetic intelligence:

- Ex: whole-body competence (athlete, dancer, hunter); or finer-grained competence (weaver, archer, lab technician, surgeon)

6. Interpersonal intelligence (knowledge of and skill in dealing with other persons):

- Ex: political leader, salesperson, religious leader, ‘wise’ man or woman, shaman

7. Intrapersonal intelligence (a person who has a good understanding of him or herself and can operate cogently on the basis of that understanding):

- Ex: persons who introspect frequently, who learn from experience and who accordingly can anticipate what they will do and how they will feel thereafter. We can as well think of others, in contrast, who, whatever their IQ, seem oblivious to their own reactions and who, as a result, make essentially the same mistake over and over again.

8. Naturalist intelligence:

- Ex: Charles Darwin. In brief, this is the intelligence that allows humans (and perhaps other species) to make distinctions in the world of nature, between one animal (perhaps a predator) and another (perhaps prey), among plants, clouds, rock configurations, and so on.

Other intelligences considered (but not officially added):

- Existential intelligence: pose and ponder big questions about life, death, love, war, indeed existence itself

- Pedagogical intelligence: teach skills and convey information to others, both those who are quite knowledgeable and those who are far less in the know

A couple key questions:

- What about emotional intelligence? “Often, I’m asked about whether I ‘believe in’ emotional intelligence. The answer is largely yes. I don’t use that term, because as far as I am concerned, emotions accompany any and all intelligences; emotions are not a separate realm, cognitively speaking. Much of what Dan (Goleman) intends by his term is covered by my ‘personal intelligences,’ inter- and intra-. From the very first, I have insisted that these two intelligences are far more closely intertwined than any others … I’m all in favor of emotional intelligence, but I insist on thinking of it—and indeed thinking of all intelligences—in an amoral way … It’s the uses to which an intelligence is put that determines whether it is benevolent or malevolent.”

- What’s the difference between an intelligence and a domain/discipline? “The difference between an intelligence (a computational capacity of the brain) and a domain or discipline (a set of practices featured in a culture or society): Put concretely, the capacity to move one’s whole body or parts of one’s body in a deliberate and skilled way entails an intelligence: bodily kinesthetic intelligence. But the culture in which one lives determines whether and how one expresses that intelligence: through sports (and, if so, which ones, boxing or fencing or jai alai); or through dance (and, if so, which form—ballet or polka or hora); or through fine motor movements (and, if so, via sewing or typing or tying knots or playing the harp); or, less happily, only for certain demographic groups or not at all.”

The Five Minds

The five minds include:

1. The Respectful Mind

2. The Ethical Mind

3. The Disciplined Mind

4. The Creating Mind

5. The Synthesizing Mind

The Respectful Mind & The Ethical Mind:

- “Two of the postulated five minds pertain to human beings living with others, both those near us (the respectful mind) and those with whom we have more remote contact (the ethical mind). My understanding of these two kinds of minds has emerged from our long-time and continuing study of good work, good play, good citizenships, and other kinds of’ ‘goods.’ These minds are incredibly important for the survival as well as thriving of our species.”

The Disciplined Mind, The Creating Mind, & The Synthesizing Mind:

- “The remaining three minds describe thinkers, learners, teachers—the minds of cognition.”

- “In conceptualizing the disciplined mind, I emphasize what it takes to master the major ways of thinking that thinkers (often scholars) have developed over the centuries: the minds of the philosopher, the psychologist, the economist, the physicist, the historian, the musical composer, the musicologist, and so on … I contend as well that meaningful synthesis or meaningful creativity are not possible until or unless one has developed a mind that has mastered one or more disciplines. To play with words, it takes discipline to master a discipline. (Rarely there are individuals who synthesize skillfully without formal training in one or more disciplines.)”

- “At its core, the creating mind solves problems or raises questions or introduces ideas or practices that are initially novel, if not unprecedented. But novelty alone is not enough—just thinking or doing ‘stuff’ in an original way does not suffice. To be judged creative, an idea or practice must be accepted in some way by a relevant community … eventually emerge as worthy of attention by other members of the public.”

- “Now we come to the heart of the matter: the line between synthesizing and creating. It’s hard to imagine any potentially creative idea or act being conjured up ‘from scratch’ … Creativity presupposes both some disciplinary mastery and some prior synthesis.“

What is the Synthesizing Mind?

The synthesizing mind: “the capacity to take in a lot of information, reflect on it, and then organize it in a way that is useful to you and (if you are skilled and fortunate) that also proves useful to others.”

- “Psychology has largely dropped the ball with respect to the illumination of this form of cognition. We have little understanding of how we humans synthesize information and then collate it in ways that are helpful to us and to others, and in ways that are either adequate, fine, outstanding, or truly creative.”

- “It is not a kind of mind that is easily or readily explained in terms of MI theory.”

- “In its pristine form, the synthesizing mind takes as its assignment the optimal organization of materials from one or more disciplines or fields or spheres of observation and tinkering. The materials should be organized in ways that are accurate, comprehensive and suited for the task at hand.”

- “Individuals can synthesize in various ways. How they do so depends on the intelligences that most characterize their own cognitive profile—the ones on which they most like to draw, and the ones most appropriate for the task at hand … I suspect that those of us who are synthesizers also draw on our other less obvious intelligences in ways that prove helpful to us and perhaps to others.”

- “Just as individuals draw on their favored intelligences in mastering schoolwork or in creating new works, so, too, those of us who are engaged in synthesizing are inclined to exploit those intelligences which we favor, and which help us to make sense of our experiences. Think of the intelligences as a chart of chemical elements: aspiring synthesizers create the particular configuration of chemical compounds that allow them to carry out their mission.”

- “Aspiring synthesizers must draw on our peculiar motivations and skills and intelligences, such as they are and such as they can be cultivated or even synthesized.”

- “Synthesis depends crucially on the quality of the questions asked and on the reasons that they are being asked.“

- “But—an important ‘but’—can such a quick and necessarily superficial synthesizer go deeper, provide more details, handle challenges, realize when a criticism is valid as opposed to being irrelevant or based on a fundamental misunderstanding? Only if the answer to these questions is ‘yes’ would I deem such a person to be a legitimate synthesizer.”

- “Metaphoric thought is clearly fundamental both in making connections and in capturing those connections in some kind of symbol system, linkages essential for many types of synthesis.”

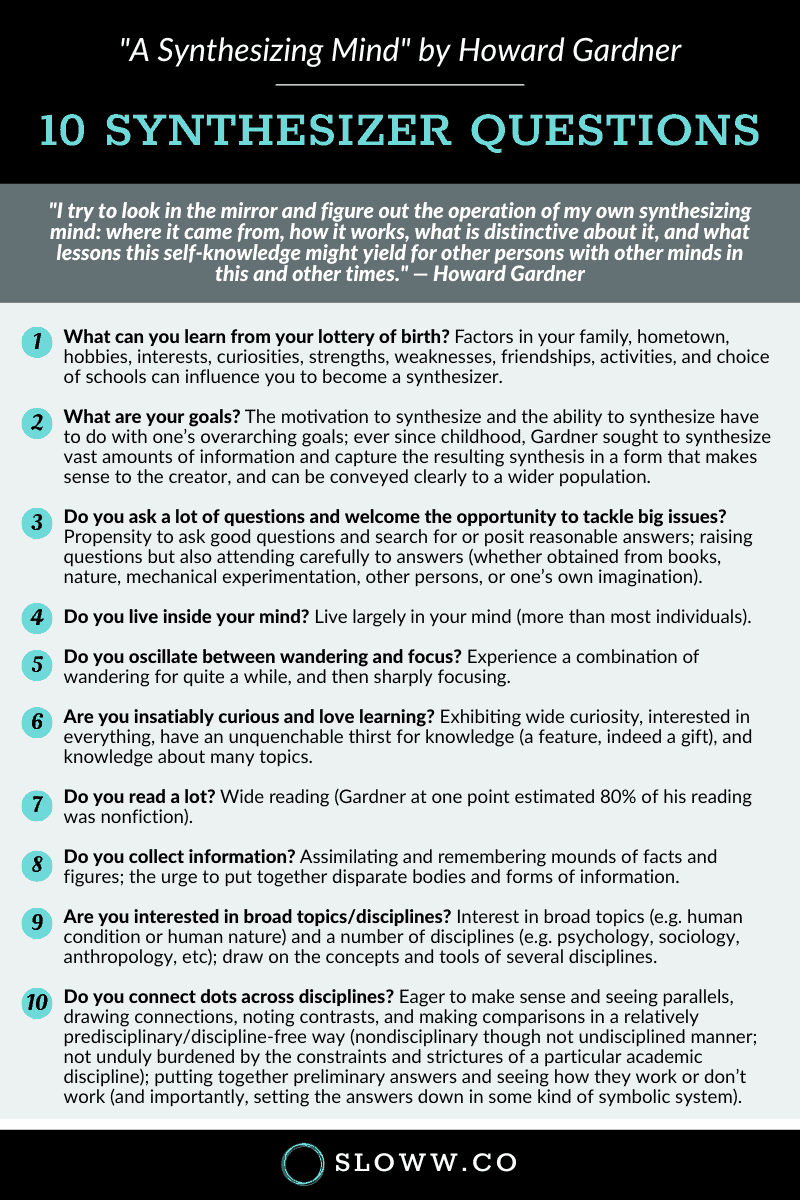

Do you have a Synthesizing Mind?

In this section, I’ve attempted to gather a vast variety of characteristics that Gardner mentions about himself throughout the book. I’ve paraphrased most of the quotes for consolidation and formatting purposes (but have stuck as close to the original quotes as possible). These are characteristics that he uses to describe himself at various times in his life (childhood, high school, college, professional life, etc). But, I think we can all use these characteristics as a guide as well. For instance, I consider myself a synthesizer and see many similarities with his descriptions.

Consider your nature, nurture, and experiences:

- “Factors in my family, my hometown, my hobbies, interests, curiosities, strengths and weaknesses, friendships, activities, and choice of schools influenced me to become a synthesizer.”

Consider your other intelligences (see MI Theory above):

- “The act of synthesizing can draw on various intelligences, and combinations of intelligences, in various ways.”

What are your goals?

- “The motivation to synthesize and the ability to synthesize have to do with one’s overarching goals.”

- “Ever since childhood, I’ve sought to synthesize vast amounts of information and capture the resulting synthesis in a form that makes sense to the creator, and can be conveyed clearly to a wider population.”

- Welcome the opportunity to tackle big issues.

Do you live inside your head?

- Live largely in your mind (more than most individuals)

Are you insatiably curious and ask a lot of questions?

- Exhibiting wide curiosity

- Raising questions but also attending carefully to answers (whether obtained from books, nature, mechanical experimentation, other persons, or one’s own imagination)

- The propensity to ask good questions and search for or posit reasonable answers

Do you love learning?

- Unquenchable thirst for knowledge (a feature, indeed a gift)

- Knowledge about many topics

- Interested in everything

Do you read a lot?

- Wide reading

- Gardner at one point estimated 80% of his reading was nonfiction

Do you collect information?

- Assimilating and remembering mounds of facts and figures

- The urge to put together disparate bodies and forms of information

Do you oscillate between wandering and focus?

- Experience a combination of wandering for quite a while, and then sharply focusing

Are you interested in multiple disciplines?

- Interest in broad topics like the human condition or human nature

- Interest in a number of disciplines (e.g. psychology, sociology, anthropology, etc.)

- Draw on the concepts and tools of several disciplines

Do you connect dots across disciplines?

- Seeing parallels, drawing connections, noting contrasts, making comparisons in a relatively discipline-free or predisciplinary way (making your own distinctions, comparisons, and connections)

- Putting together preliminary answers (in a nondisciplinary though not undisciplined manner) and seeing how they work—or don’t work; and importantly, setting the answers down in some kind of symbolic system

- Eager to make sense and connections, but not unduly burdened by the constraints and strictures of a particular academic discipline

- Gardner says: “I am interested in psychology and the mind, broadly construed … I also esteem interdisciplinary studies.”

A Continuum of Synthesis (Types & Mediums)

“One could write a book about ‘varieties of syntheses’ and ‘varieties of synthesizers.’“

What is a work of synthesis?

- “A work of synthesis—putting together many strands of information.”

- There are works of synthesis that are principally about other people’s ideas, and works of synthesis that are principally about your own ideas (or a mix of both).

- “Many assignments in school—for example, book reports, term papers, essay questions on an examination—call at least modestly for the synthesizing mind.”

Conventional Synthesis vs Original Synthesis:

- Conventional Synthesis: “Just bringing concepts and ideas together in a way that relies heavily on common sense or conventional wisdom and would unlikely be disputed in any way.” (Example: a standard textbook)

- Original Synthesis: “An account that demonstrated that I had read and mastered the existing material (usually texts, but this could also include works of art) but went beyond the task of weaving sources together and instead put forth new ideas, contrasts, and questions.” (Examples: Darwin, Hofstadter, etc.)

“Hedgehog” Syntheses vs “Fox-like” Syntheses:

- “Some syntheses aim to bring lots of materials together to make a single grand point. We could call those ‘hedgehog’ syntheses” (Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species is an outstanding example).

- “‘Fox-like’ syntheses delight in their plurality” (Carl Jung’s positing of various personality types might qualify).

Synthesis as art:

- “First of all, synthesizing involves artistry. To create a work or treatment of significant size and to convey it effectively to others requires a sense of form, of arrangement of parts, of the attention and predilection of audiences, of launching, development, and closure. All of these skills are identified particularly with the arts more so than with the sciences, where the behavior and accurate description of reality has to take primacy. I propose that synthesizers are aspiring artists, and that they—and that includes me—draw from the art form with which they are most comfortable—be it musical, literary, architectural, terpsichorean, or some other aesthetic means of communication. But unlike ‘pure’ artists, synthesizers cannot start from scratch and proceed in any and all directions. Rather, they are restricted, or if you prefer empowered, by the data that they and others have collected, be it historical, literary, or psychological. And accordingly, these aspiring synthesizers need some ways to arrange and rearrange those data, until they find a solution that is adequate, accurate, communicable, and, as a bonus, aesthetically pleasing.”

Media/Mediums:

- Textbooks

- Books for the general public

- Peer-reviewed articles

- Essays and reviews in the popular press

- “The kinds of synthesizing on which I have focused in these pages might be called large-scale synthesizing, the sort that scholars undertake and that is found in books, summary articles, or major artistic or design endeavors. But we also live in an era where rewards come to those who can synthesize in a versatile way: provide a brief summary of a complex set of ideas; write a blog; give a TED talk; do an effective interview on radio, TV, or a podcast; create a stimulating tweet and marvel if it goes viral.”

Gardner’s Personal Synthesizing Process

“From early on I have been disposed to ask questions, to reflect about them, to gather whatever data are available by whatever means I have at my disposal, and then, crucially, to organize those data in ways that made sense to me, and, I hope, to others as well. Thanks to the accidents of family, culture, the historical moment, and, yes, genes, I have had the privilege of being able to lead a life of the mind, and to put forth syntheses that make sense to me, and, at least at times, to others as well. I have done this chiefly through writing books, though as other media have become available or salient, I’ve been able to draw on them as well.”

In a nutshell:

- “My natural inclinations, dating back to high school if not to second grade, were to read, observe, chatter, synthesize, write, and rewrite.” … (he also mentions “reading, questioning, discussing, synthesizing, and writing.”)

- “(Works of synthesis are) a valid and particularly precious (and possibly particularly precarious) form of knowledge. It’s what I do and what I think I am good at—my comparative strength, so to speak.”

Other intelligences used:

- “As a synthesizer, I believe that I draw on two other intelligences (music & naturalist).”

Curiosity kicks off the flywheel of the process:

- “For whatever reason, I have always been curious. I become interested in things I hear about, read about, or observe as I make my way around the world. I investigate them with whatever means are available. And I like to write about them, both to make sense to myself—how do I know what I think until I have seen what I have written?—and to convey my thoughts to others who may share my curiosity.”

- “I was curious; I could read rapidly and widely; I enjoyed synthesizing and resynthesizing. I could also write quickly and clearly; and I could address various audiences, including the intelligent general reader. And so, while continuing for decades to contribute modestly to the peer-reviewed empirical literature, and training my students in that science and art, I became more of a writer, and strove (with limited but not negligible success) to be a public intellectual.”

His process:

- “As an inveterate reader and synthesizer of ‘the literature,’ I was continuously trying to put these parts of the puzzle together to build a model of artistic competence: its components, their integration into smoothly functioning artistry.”

- “I take lots of notes, organize and reorganize them repeatedly, speak to colleagues and friends incessantly about what I have been thinking.”

- “I have constant conversations with myself in my own mind, often creating sentences that could be, and sometimes are, dictated—decades ago into a tape recorder, nowadays into my cell phone.”

- “Then I sit down and write . . . and write, and write. I am not one of those writers who obsesses about the first sentence, or who allots himself five hundred words a day, or who revises the first chapter until it is perfect before moving on. No, I just spit it out (or, if you prefer, crank it out). At least a chapter at a time, and, as far as possible, the whole book in one fell swoop—more precisely, in an uninterrupted week or two of several hours a day at the keyboard. I need to—I want to—get a feeling for the whole enterprise, what the whole book will feel like, even what it will look like in so many words.”

- “Those of us who are scholars typically select our own topic and spend the time (and as needed, and as available, the money or other resources) examining something systematically. We pursue the topic in as many ways as appropriate and feasible, and seek to relate it systematically to previous work in the field. We never know in advance when we will be done, and it may well be the case that at the end of the day (or, indeed, the decade), we don’t find much of interest or we don’t have confidence in what we think or believe that we have actually found. And so we may write it up, or not.”

- “Our words, our terms, our concepts are intended to be neutral, or to use an adjective that is less familiar but more illuminating, we aspire to a disinterested stance. We attempt to describe a state of affairs as we have observed and analyzed it, not to prejudge or skew our findings and conclusions. But if we are successful, our very acts of conceptualization and writing may change how people talk and think. And, paradoxically, this very change may in the end—or, more precisely, in the next iteration—make our conceptualizations (as initially published) less accurate, less relevant, more like ‘period pieces’ than the ‘last word.'”

His goal(s):

- “I am much less interested in writing the definitive work, or the ultimate synthesis, than I am in putting ideas and items together for the first time—or at least early in the game. I want to put things together as best I can—the initial tentative synthesis, not the last word—and then move on.”

- “I prefer to think of myself as having a lifelong mission, or a small set of missions, and continuing to pursue this overarching endeavor in various ways over the course of decades.”

- “We develop ideas and try to give them a push in the right direction.”

- “Here’s what’s important: as scholars, we assembled these data and synthesized our impressions and our numbers, in as powerful a way as we could. And over and above the data that we arrayed, we hoped that our writings, individually or collectively, could change the conversation about human beings at a particular time in a particular social and cultural context.”

“May synthesizing minds thrive.” — Howard Gardner

You May Also Enjoy: