This is a book summary of Teaching Complex Ideas: How to Translate Your Expertise into Great Instruction by Arnold Wentzel (Amazon).

Quick Housekeeping:

- All content in “quotation marks” is from the author (otherwise it’s minimally paraphrased).

- All content is organized into my own themes (not necessarily the author’s chapters).

- Emphasis has been added in bold for readability/skimmability.

Book Summary Contents:

- About the Book

- Ideas & Elaboration

- Explainers & Explanations

- Forgetting & Interest

- Understanding & Reasoning

- Patterns

- Assessment & Testing

Translating Expertise into Great Instruction: Teaching Complex Ideas by Arnold Wentzel (Book Summary)

About the Book

“Integrating insights from learning science with practical guidelines and stepwise approaches, Teaching Complex Ideas helps educators masterfully translate their expertise into easy-to-understand, interesting, and memorable instruction.”

- “This book has a unique unifying theme: good teaching starts from ideas.”

- “Great teachers of complex subjects are those who are idea-centered – who make ideas matter to their students. They are student-centered, not by explicitly aiming to be so, but as a natural result of the way in which they teach the content.”

- “The teachers that these students remember are often not those who understood the ideas of complex subjects, but who understood the ideas well enough to be able to explain them and make them interesting to others.”

- “To summarize this book: professor-experts are those that help students grasp the critical ideas so that they continue to expand that understanding for as long as they live. They teach less, explain better, encourage forgetting, upset preconceptions, release natural reasoning, assess authentically, notice more and exploit the uniqueness of learning events.”

- “If you are reading this book, you probably already understand your subject. But it is not enough. This book takes you further: it aims to show you how to transform your understanding and expertise into great teaching. It explains how experts should think in order to make their ideas teachable – that is, clear, interesting, memorable and able to be expanded into future learning.”

Future focus:

“When you teach, you should engage with students as if they are, or are becoming, the kind of person you want them to become. This makes the critical ideas stand out.”

- “Don’t think of your audience simply as who they are at the moment. Rather, think of them as who they will be in the future, after they are transformed by the understanding you want them to have.”

- “If you teach to get your students to learn ‘to be’ or ‘to become’ something, you will choose much more carefully which ideas you want them to engage with. You now aim to change the audience, so the audience matters.”

- “Understanding the ideas that you teach should ultimately transform your students in some small way. But you need to be sure that this transformation is not too radical: it needs to be within the sphere of the ‘adjacent possible’. Steven Johnson (2010) describe the adjacent possible as ‘a kind of shadow future, hovering on the edges of the present state of things, a map of all the ways in which the present can reinvent itself’.”

- “The ‘shadow future’ is what you want your students to be, or become, and the ‘present state of things’ is their current understanding and interests.”

- “The seeds of students’ transformation should already exist in their present state, and they ‘reinvent’ themselves as you connect the critical ideas to their present state.”

Ideas & Elaboration

“If we want people to understand as much as possible, we should teach them as little as possible. Good teaching starts when we know what not to teach … Students just need to understand that which can help them to expand and revise their understanding indefinitely – and that is often much less than expected.”

Critical ideas:

“One can understand physics, and most other subjects, because it is possible to reduce them to ‘laws’ or ‘critical ideas’ from which less important ideas are derived.”

- “You cannot identify the critical ideas unless you first know whom you are teaching, and what would be important to them (not to you) when they put their understanding to use.”

- “It takes a high level of understanding to know what is critical, what can be simplified and which details can be left out without adversely affecting the learning process in the future.”

- “For a person with little understanding, everything is important. In contrast, good professors reveal their understanding in their ability to cut to the heart of a topic and to recognize the deeper principles. Instead of covering as many ideas as possible, they explore a few critical ideas in depth from different perspectives.”

- “It is better to teach a few critical ideas from many perspectives, than as many ideas as possible from a single perspective.”

- “The critical ideas are the seeds from which everything grows.”

- “Explanation that starts from the critical ideas and moves outward, is the fastest way to put a student on the path towards expertise.”

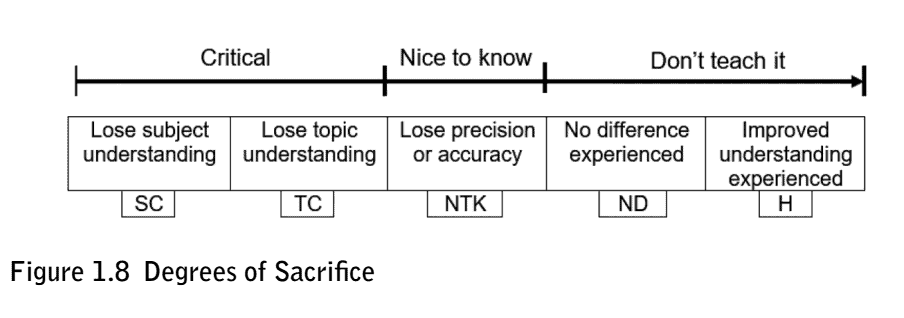

5 types of ideas:

- Subject-critical (SC) idea: An idea that, if it is not taught, will make it difficult for students to understand most topics in the subject as a whole.

- Topic/theme-critical (TC) idea: An idea that, if it is not taught, will make it difficult to understand most of the ideas in a particular topic.

- Nice-to-know (NTK) idea: An idea that, if it is not taught, will cause students’ understanding to be less complex or precise compared to an expert.

- No-difference (ND) idea: An idea that, if it is not taught, will make little difference to students’ understanding.

- Harmful (H) idea: An idea that, if not taught, will actually make the topic easier to understand for now.

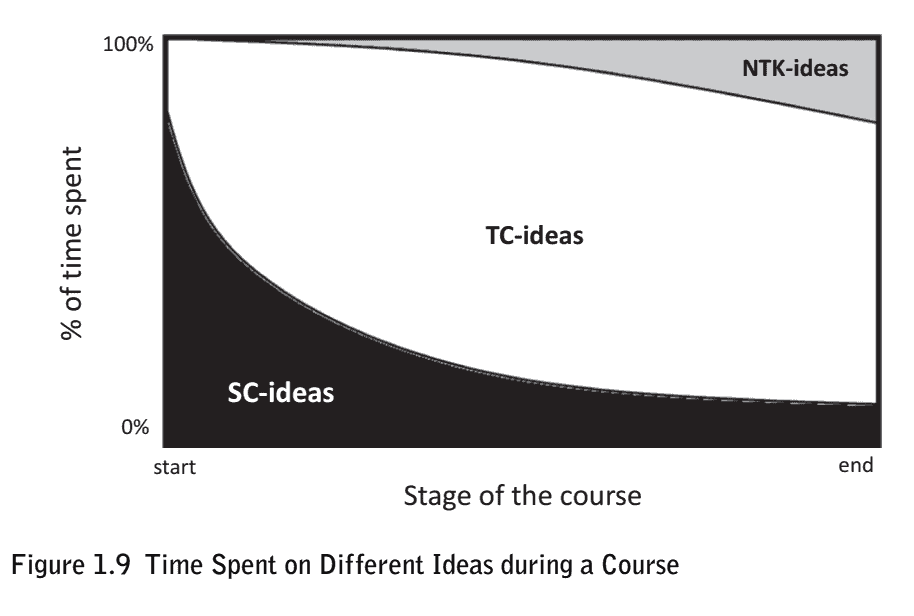

Time & trade-offs:

“You should not teach nice-to-know ideas if students do not yet understand the important ideas, and you should not teach important ideas if students do not understand the critical ideas. Given the limited time, we should therefore not teach the majority of the ideas.”

- “In a teaching situation, the scarcest resource is time. We simply cannot teach everything. The more time we spend helping students to understand one idea, the less time there is to support the understanding of other ideas.”

- “When deciding whether to teach an idea, do not ask yourself what the students will gain from it. Rather, ask yourself what the students will lose if you do not teach it. Those ideas that cause them to lose the most if they don’t understand them are the critical ideas.”

Elaboration:

“Elaboration should do two things: (1) grow the lecture from the critical ideas; and (2) deepen the students’ understanding of these same critical ideas.”

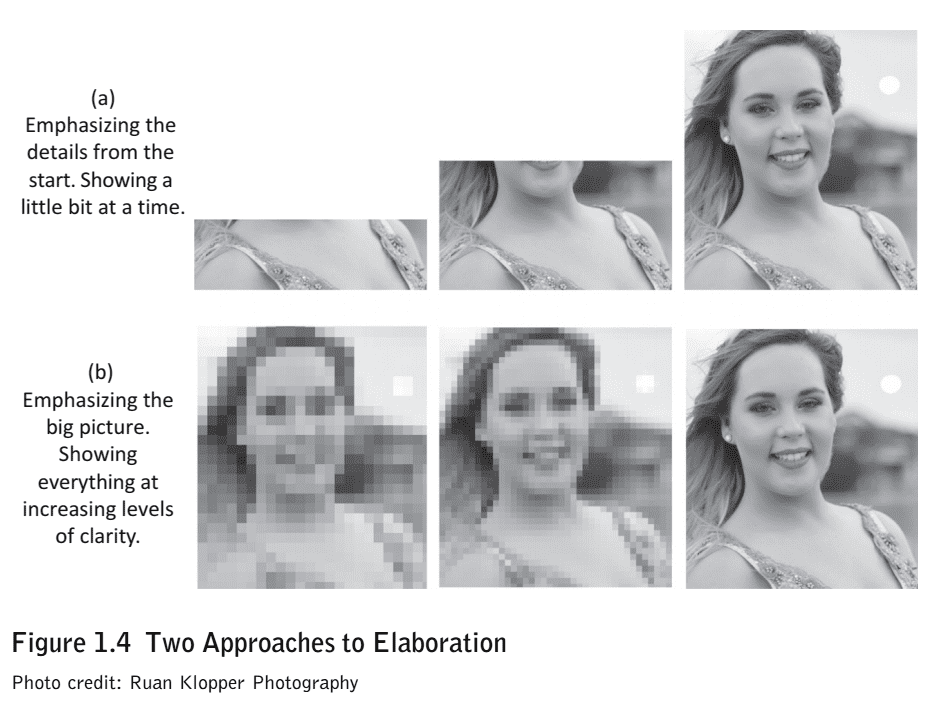

- “More useful to see the big picture from the start, but not in as much detail, and to fill in the details over time (Figure 1.4b). In this way, the students understand from the beginning and deepen their understanding gradually.”

Explainers & Explanations

“When explaining, the challenge is to reformulate complex ideas, so that your audience can understand them in terms of things that they already understand at the time of the explanation.”

Great explainers:

- They understand their audience (more specifically, they know what their audience already understands before the explanation starts).

- They understand the topic they want to explain (so well that they can distinguish between the critical and peripheral ideas).

- They understand how to bring the two together (specifically how the critical ideas are connected to the ideas of the audience).

Great explanations (5 elements):

1. Familiarity that breeds understanding

- Connect, Relate, Evoke: Connect new ideas to what the audience already knows through analogies/examples. Relate new ideas to what is happening in the world. Explanations need to evoke emotion.

2. Organization around critical ideas

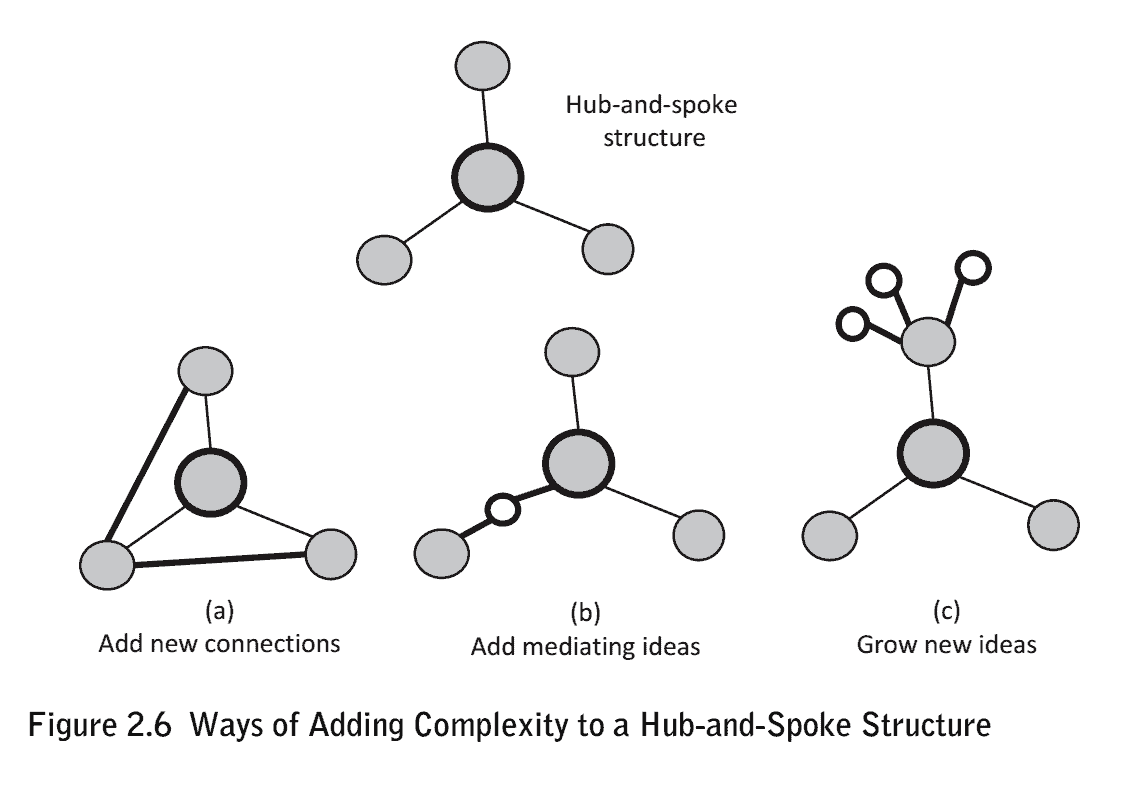

- Hub-and-Spoke: The hub-and-spoke structure is most effective if it has the critical idea(s) as the hub at the center. A good explanation then gradually adds details, while still remaining connected to the hub-and-spoke structure.

3. Gradual addition of complexity through connections

- Connections: Ideas are created from connections between previous ideas (any topic is made up of ideas within ideas within ideas like Russian dolls). Without connections, there can be no new knowledge and understanding, and it is only when we make connections between familiar ideas that we gain an understanding of new ideas.

4. A linear sequence that strengthens connections

- Hub-and-Spoke sequencing: To convert a network structure of knowledge into a linear teaching sequence, first convert it into a hub-and-spoke structure so that the critical ideas are clear. Then, when teaching, start at the hub and move outwards to the peripheral ideas, periodically returning to the hub before venturing further outwards. This gives rise to the repetition of ideas, but the ideas that are repeated are always at the center or hub of the ideas being explained. This ensures that the central ideas are understood and integrated by the students before the next layer of complexity is added. An appropriate linear sequence, therefore, strengthens the connections and reinforces the structure through productive repetition. The same repetition would occur at higher levels of complexity. Every time an idea gets repeated, it is done with new knowledge in mind and so it offers a slightly different perspective each time.

5. Provocation of thought

- Thinking & Testing: For the connection to be integrated into the existing understanding of the student, she or he has to think about the ideas. This can be done by making the ideas interesting through inciting actions that require thought, or giving assessments that are authentic and exploit the testing effect. Unless the explanation makes a student think about the ideas, it will have no long-term effect on the student’s understanding.

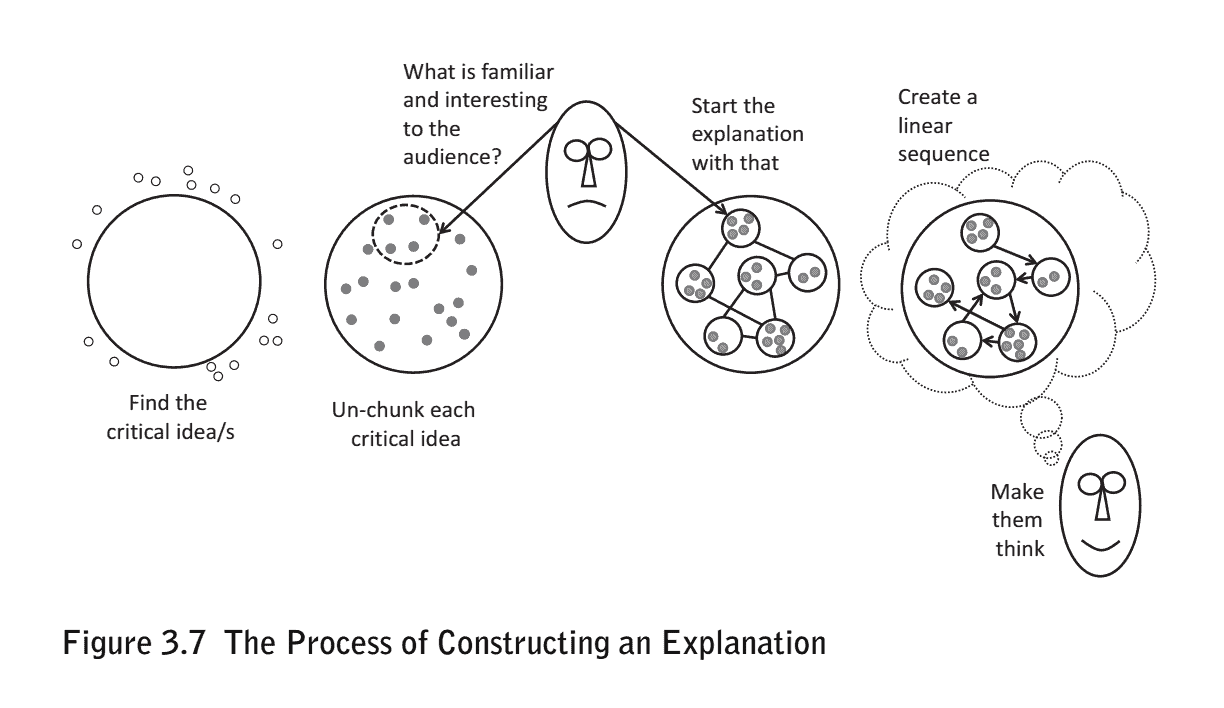

Explaining complex ideas clearly (6 steps):

“Before an explanation, the student is confronted with a loose collection of facts and ideas that do not make any sense. To make sense of these facts, the teacher organizes them around a few critical ideas, and then gradually makes those ideas more complex by adding new connections and introducing new ideas. Whenever new ideas are introduced, they have to be connected to the already familiar ideas in something that resembles a hub-and-spoke structure, and this then gives rise to even more new connections. The actual explanation when delivered to the students has to proceed in a sequence that starts from ideas to which the learner can relate, and then connects from there to the critical ideas, and then moves outwards along the hub-and-spoke structure. To ensure that the connections are made more permanent, the student has to think about the ideas and their connections.”

1. The critical ideas for the audience

- Chunking: Chunking integrates ideas and reduces the number of ideas we have to keep in mind, thereby reducing our cognitive load. Once we have chunks, we may recognize that they form patterns or groups (these groups are categories that divide the chunk into smaller parts again).

- Un-chunking: Finding the ideas from which the chunks are formed (do this until you find the ideas that can connect to the audience’s current understanding and build explanations with these). Un-chunking leads us to the building blocks for explanations. Un-chunking helps us to derive the simple and familiar ideas with which to build an explanation that the audience can understand. In an explanation, we will then connect these building blocks, and so make the hub-and-spoke structure more complex.

2. Generate the building blocks of the explanation

- Part-whole: Un-chunk up (is this idea part of something bigger?) and un-chunk down (what is it made up of?)

- Similarity-dissimilarity: Un-chunk across by asking what the idea can be compared to (an analogy) or contrasted to, and what would be good examples or non-examples.

- Cause-effect: Un-chunk up diagonally (what can cause it?) and down diagonally (what are the effects or what does it lead to?)

- Reason-action: Un-chunk up diagonally (what is the reason for it? Why do we need it or use it?) and down diagonally (how does it work? How do we use it?)

3. Where to start?

- Re-chunking: With the building blocks ready, we now need to choose: which ones to use; which ones to avoid for now; and which ones may be potential starting points. The most fundamental rule of starting an explanation is: start with something relevant to the topic that is also familiar to the audience. Some of the most common ways to start are simply to: state the critical idea; raise a provocative question based on the critical idea; tell a story that illustrates the critical idea or talk about the benefits of understanding the critical idea.

4. Connect the building blocks

- Metaphor & Analogy: The most effective way to make an idea appear familiar is through metaphors and analogies. If the situation allows, another way is to simply show how the idea is applied in a familiar context.

5. Putting ideas in a sequence

- Seeds: Get the audience to first understand the idea in broad terms, and then come back and gradually, layer by layer, fit more details into the idea. Simple explanations are more like seeds that contain the potential for the details to grow from them. The details only grow when the understanding of the simple explanation awakens the growth of these seeds.

6. Provoke thinking

- By getting one to think, I can also stimulate them asking the kinds of questions that will reveal whether they are ready for another layer of complexification.

Forgetting & Interest

“Memory is creation and recreation, not storage and retrieval.”

Forgetting:

“Memory is not about adding and accumulating facts, but rather about forgetting as many facts as possible.”

- “If something is not worth remembering, it should be forgotten, and it is this forgetting that makes memory valuable.”

- “We have to forget in order to see patterns, connections, chunks of information or critical ideas.”

- “If we could not forget what is noncritical, we would not see what is critical. And without critical ideas, we would not have something around which to grow a network of related ideas.”

Interest:

“The most obvious definition of ‘interesting’ is that of something that holds attention … When you are fascinated by something, your attention locks onto it, and you are unable to move onto to something else.”

- “Interestingness is a process that arises from the interaction of three things: fascination (getting attention), fun (using attention), and fumbling (disrupting attention).”

- “Interest serves understanding by enhancing memory and motivation. If something is interesting, we think about it. The act of thinking creates new connections and strengthens existing connections, and it is only the ideas we think about that we remember. In addition, interest often generates an emotive response, and, if thinking is accompanied by emotion, it further enhances the memory of the ideas involved.”

- “By inducing thinking, interest also makes understanding possible.”

Understanding & Reasoning

“Understanding is the ability to compress information into a much smaller number of connected ideas; and then, by using reasoning and a bit of imagination, generate new information, even in situations not experienced before.”

Understanding:

“If you can find the 20% best-connected ideas, and only teach them well from different perspectives, students should gain around 80% of the understanding.”

- “The understanding of a subject is a networked system.”

- “Understanding is a network of connected facts and ideas, and the brain that enables this understanding is also a highly connected system.”

- “Understanding one idea enables us to perceive the ideas that are connected to it by logic or experience. The well-connected ideas are the powerful ones.”

- “Understanding will enable you to construct a network of relatively few critical ideas, and gradually infer new ideas and connections as required.”

- “Understanding is the ability to compress a vast collection of facts into a network of a few critical ideas from which further ideas can be generated. To create and expand this network, facts and ideas are connected.”

- “Understanding is not achieved by merely storing more facts; rather it involves connecting facts and ideas, thereby changing the knowledge network structure (also called ‘conceptual change’).”

- “Novices’ knowledge often has little or no structure, while experts’ understanding is like a densely connected network.”

- “Experts build a connected network structure of ideas in their subjects and organize this network around a few critical ideas.”

- “For experts, any single fact or idea is connected to many others, so if we let them start anywhere and then simply follow the connections in any direction.”

- “Experts do not simply see the connections, they also recognize the conditions under which the connections may or may not be valid, and this provokes them to always search for ways to improve their understanding.”

Reasoning:

“Reasoning causes the seeds of a few critical ideas to bloom into a forest of smaller, connected ideas – it unlocks the full power of understanding.”

- “Reasoning is commonly defined as the process of drawing new conclusions from a pre-existing set of information. It usually involves deductive logic, but in the cases of inductive and abductive reasoning, it may also require some imagination. Mercier et al. (2016) point out that this is more accurately described as ‘inference’. They explain that reasoning is, in fact, a more specialized form of inference: it is inference guided by the process of finding, using, and evaluating reasons. It is not simply making claims (like ‘It is going to rain later.’), but making arguments: making a claim, backed by evidence, warrants, counterarguments, and qualifications.”

- “Teaching students how to reason with the important ideas will allow them to expand their understanding and go beyond what was taught in the course.”

- “The ideal understanding is a reduction of knowledge to a connected essence from which most other ideas can be inferred through reasoning or imagination. Explanation does not try to simply remove inconvenient complexity, it enfolds it into a form of understanding from which the complexity can gradually unfold.”

- “By synthesizing opposing views, we can take advantage of the information on both sides, instead of trying to destroy the opposing side and the information it holds. Many creative breakthroughs are often the result of new ideas that emerge from synthesis.”

- “We become experts, not by accumulating facts, but by connecting them and then reasoning with them to make sense of situations and ideas that were previously unknown to us. In this way, reasoning enables understanding to expand to its full potential.”

Patterns

“To gain an understanding of a subject or topic, we need to find patterns.”

- “As we look for connections between facts, we start seeing patterns, that is, commonalities and regularities. This enables us to eliminate what is redundant and identify the few critical ideas from which most other ideas can be derived. Critical ideas then become the seeds from which the other ideas can gradually grow.”

- “If we are fascinated with the topic, we will have fun looking for patterns. Finding these patterns helps us to see connections and chunks, compress the information and try out the ideas to see how well we can generate new information.”

Fascination with patterns:

“When we teach, we are also selling our ideas in exchange for students ‘paying’ attention. We need this ‘payment’ for the learning transaction to begin, and by offering opportunities for fascination, we make students willing to pay attention.”

- “Fascination does not happen by talking about the steak or the idea itself, no matter how fascinating it is to us. It happens when we are able to connect the idea to our audience in a way that they can see that it is relevant to them. This means that you need to get to know your audience, what their goals are and what they care about.”

- “The deeper the idea connects to something that matters to a person, the more fascinating it will be to them.”

Fun figuring out patterns:

“For something to remain fun, it has to push you to the limits of your ability.”

- “This is similar to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s (1990) idea of ‘flow’. We are in a state of flow when we are fully engaged with what we are doing. It is a dynamic process that can only be maintained if the level of challenge rises as we become more skilled.”

- “We remain in the flow channel as long as our skill level and the challenge we perceive are more or less in balance. When our skill level exceeds the perceived degree of challenge, we get bored, and when the challenge exceeds our skill, we become anxious or frustrated and give up.”

Fumbling toward new patterns:

“To continue learning, students have to periodically open up to new ideas, which happens when their existing ideas are disrupted.”

- “Disruption makes students realize that their old patterns do not work as well as expected, and this causes them to fumble (in the sense of struggling to use old ideas and trying to clumsily reach for anything that may help).”

- “If an idea disrupts us too little, we think it is obvious and hardly pay attention. Disrupt us too much and we think the idea is crazy and we resist it. However, with just enough disruption, we become interested in changing. We start to think, and even if we don’t agree with the idea, our minds have been permanently stretched.”

Assessment & Testing

“It is no use to have excellent explanations if students never think about the ideas explained. Without assessment, all the effort that a teacher puts into explanations is lost because students do not form strong connections. By putting the testing effect to use, not only is the effect of good explanations maintained, it is, in fact, amplified.”

Assessment:

“Assessment is, in itself, an act of learning.”

- “Assessments will promote intrinsic motivation if they offer meaningful and authentic challenges for students. Such assessments make students think about the questions of the subject by connecting this to the questions in their own lives and questions in the real world.”

- “What you intend for students to learn is also what you should teach, and this, in turn, should determine what is assessed. If an assessment accurately measures the intended learning, and only the intended learning, the assessment is said to be ‘valid’.”

- “The most successful learners are those that can assess their own learning. They are the ones who can recognize their own needs for improvement and plan their own learning. Most experts and some of the most exceptional people on this planet are auto-didacts, and it is only possible to become one if you have the ability to assess yourself. Self-assessment helps students to develop this meta-cognitive skill.”

Testing effect:

“The testing effect shows that formative assessments have a bigger and longer-term effect on learning than teaching, revision or cramming – and it allows people to remember more and with less effort.”

- “Assessment is a kind of spaced repetition, but reading is not. Simply reading the content does not count as a repetition because it does not usually involve thinking. But assessments, if designed correctly, require thinking, and this is what activates the benefits of the testing effect.”

- “The conclusion is that repetitive reading (what we mistakenly call ‘studying’) is not as good as being tested on what you just read when it comes to remembering something.”

- “Cramming is painful, boring and inefficient; while the simple act of testing, or self-quizzing, connects the ideas to your memory with less suffering and keeps it there longer.”

- “Professors who focus on the process of learning tend to have less cheating. They pay less attention to how well a student does in any single performance and place more emphasis on how well the student is progressing towards mastery. The goal is not a specific mark but a well-specified goal of mastery. Those who emphasize mastery will give students many assessment opportunities and also give them feedback on their progress after each opportunity. Such opportunities will be mostly formative assessments that aim to move the student closer to mastery and exploit the testing effect.”

You May Also Enjoy: