“Life is just one damn thing after another.” — Anonymous

In my research on workism and post-workism, I discovered another concept: “total work.”

Total work seems to be the epitome of workism. This is also timely given all the news coverage of Jack Ma, billionaire co-founder of Alibaba, endorsing “996” for Chinese workers—working 9am to 9pm, six days a week. A 72-hour workweek. The New York Times says, “996 is China’s version of hustle culture.” Ma followed up his initial comments with:

- “As I expected, my comments internally a few days ago about the 996 schedule caused a debate and non-stop criticism. I understand these people, and I could have said something that was ‘correct.’ But we don’t lack people saying ‘correct’ things in the world today, what we lack is truthful words that make people think.”7

In the spirit of truth and thinking, we are going to ask some big questions in this post.

I came across the concept of total work through Andrew Taggart—and, oh man, has he opened my eyes and expanded my mind to an entirely new level of thinking about work: the history and evolution of work, the meaning of work (and life for that matter), and where work should be headed in the future. Total work is the most profound concept I’ve come across lately; it’s a good example of this quote for me:

- “The mind, once stretched by a new idea, never returns to its original dimensions.” — Oliver Wendell Holmes

Since discovering Taggart, I’ve devoured his writing on his blog, LinkedIn, and Quartz. This post covers the highlights of everything I’ve read and learned so far.

Who is Andrew Taggart?

Andrew Taggart describes himself as a “a practical philosopher, Zen Buddhist, and entrepreneur.”

Possibly the best way to get introduced to him is by watching his TEDx Talk How Work Took Over The World:

In his talk, Taggart says:

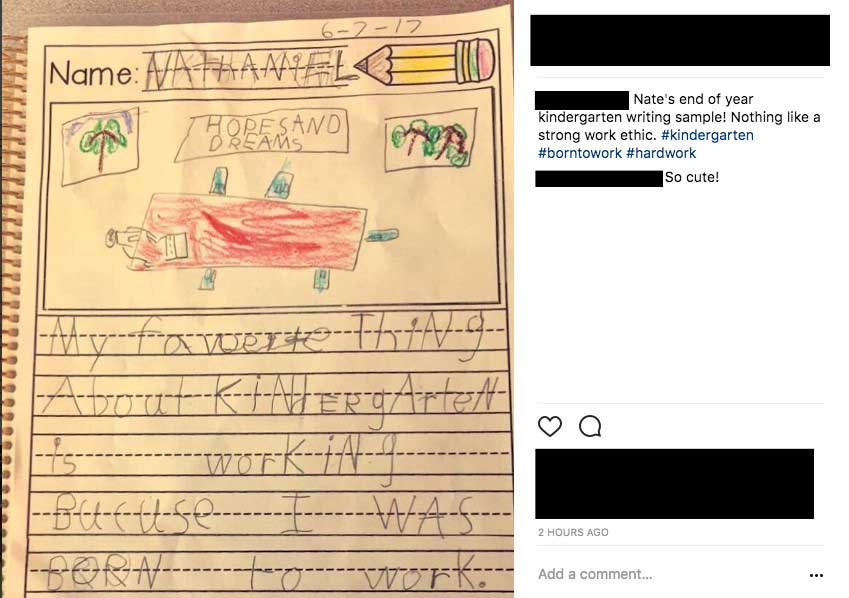

- “This long journey from work being the worst sort of thing to its being the very best sort of thing helps to explain how Nathaniel, the 5-year old boy I mentioned earlier, could come to believe that his natural identity was that of a worker. That is to say his destiny, his very reason for being, was, is, and shall be, to work.”

If you skipped the video and are wondering who Nathaniel is, he is a 5-year old boy who wrote this in his kindergarten class:

Is this “cute” like one of the comments suggests? Or, are there incredibly deep questions that we should be asking humanity at this point in our collective journey?

What is work? What is the meaning of work? Are humans born to work?

Andrew Taggart has investigated and philosophized about these very questions.

What is Total Work?

“Total work” was coined by German philosopher Josef Pieper in his book Leisure: The Basis of Culture (1948). Pieper started asking the tough questions—in his own words:

- “What is normal is work, and the normal day is the working day. But the question is this: can the world of man be exhausted in being ‘the working world’? Can the human being be satisfied with being a functionary, a ‘worker’? Can human existence be fulfilled in being exclusively a work-a-day existence?”4

Maria Popova, author of Brain Pickings, describes Pieper’s work as:

- “A magnificent manifesto for reclaiming human dignity in a culture of compulsive workaholism, triply timely today, in an age when we have commodified our aliveness so much as to mistake making a living for having a life.”4

Andrew Taggart is picking up and building upon Pieper’s work, and defines total work as:

- “‘Total work’ is the process by which human beings are transformed into workers and nothing else. By this means, work will ultimately become total, I argue, when it is the centre around which all of human life turns; when everything else is put in its service; when leisure, festivity and play come to resemble and then become work; when there remains no further dimension to life beyond work; when humans fully believe that we were born only to work; and when other ways of life, existing before total work won out, disappear completely from cultural memory.”¹

What does a Total Worker Look & Feel Like?

What a Total Worker looks like:

- “What is a typical day in the life of a Total Worker like? The Total Worker (TW) wakes up early because TW has a lot to get done. Immediately TW reaches for the phone in order to put out any fires. Next, TW goes on to meditate for exactly 10 minutes. Next, TW eats a light breakfast and then hits the gym. Afterward, TW bikes to work while listening to a podcast. And, at work, TW spends the entire day…above all trying to optimize productivity. Now and again, TW does take a break on the grounds that doing so could enhance productivity even more. After a 12 to 15 hour workday, TW finally heads home, all the while receiving Slack notifications long into the night. Exhausted, TW finally goes to bed, while believing still that sleep is in the service of more work.” — Andrew Taggart

What a Total Worker feels like:

- “Together, thoughts of the not yet but supposed to be done, the should have been done already, the could be something more productive I should be doing, and the ever-awaiting next thing to do conspire as enemies to harass the agent who is, by default, always behind in the incomplete now. Secondly, one feels guilt whenever he is not as productive as possible. Guilt, in this case, is an expression of a failure to keep up or keep on top of things, with tasks overflowing because of presumed neglect or relative idleness. Finally, the constant, haranguing impulse to get things done implies that it’s empirically impossible, from within this mode of being, to experience things completely.” — Andrew Taggart¹

“TW’s life is a burden waiting to burn out in despair.” — Andrew Taggart

“The taskification of the world is correlated with the burden character of total work.” — Andrew Taggart

“Burden” is a recurring theme you’ll notice throughout. Much of this burden is self-inflicted and of our own making. Life shouldn’t be an experience that we just “get through.” There are ways to design a lighter life.

Some Quick Notes on “Usefulness”:

Emphasis underlined by me.

Taggart goes on to describe Total Workers:

- “For unlike someone devoted to the life of contemplation, a total worker takes herself to be primordially an agent standing before the world, which is construed as an endless set of tasks extending into the indeterminate future. Following this taskification of the world, she sees time as a scarce resource to be used prudently, is always concerned with what is to be done, and is often anxious both about whether this is the right thing to do now and about there always being more to do. Crucially, the attitude of the total worker is not grasped best in cases of overwork, but rather in the everyday way in which he is single-mindedly focused on tasks to be completed, with productivity, effectiveness and efficiency to be enhanced. How? Through the modes of effective planning, skillful prioritizing and timely delegation. The total worker, in brief, is a figure of ceaseless, tensed, busied activity: a figure, whose main affliction is a deep existential restlessness fixated on producing the useful.”¹

I’m not sure I would have ever guessed that the simple word “useful” would come up in my reading so often recently. In fact, it’s the primary driver behind Elon Musk—who also happens to subscribe to workism and total work 80+ hour workweeks:

- “I like to get things done. I like to be useful. That is one of the hardest things to do…is to be useful.” — Elon Musk

- “My goal is try to do useful things, try to maximize the probability that the future is good, make the future exciting…something you look forward to.” — Elon Musk

But, is usefulness really the goal? Let’s go back to the 1930 essay Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren by John Maynard Keynes:

- “When the accumulation of wealth is no longer of high social importance, there will be great changes in the code of morals. We shall be able to rid ourselves of many of the pseudo-moral principles which have hag-ridden us for two hundred years, by which we have exalted some of the most distasteful of human qualities into the position of the highest virtues.”

- “We shall once more value ends above means and prefer the good to the useful. We shall honour those who can teach us how to pluck the hour and the day virtuously and well, the delightful people who are capable of taking direct enjoyment in things.”

How did we get to Total Work in the First Place?

If you’re able to boil down the history and evolution of work into a few paragraphs, here’s a solid attempt by Taggart (borrowing from the philosopher Edward Craig):

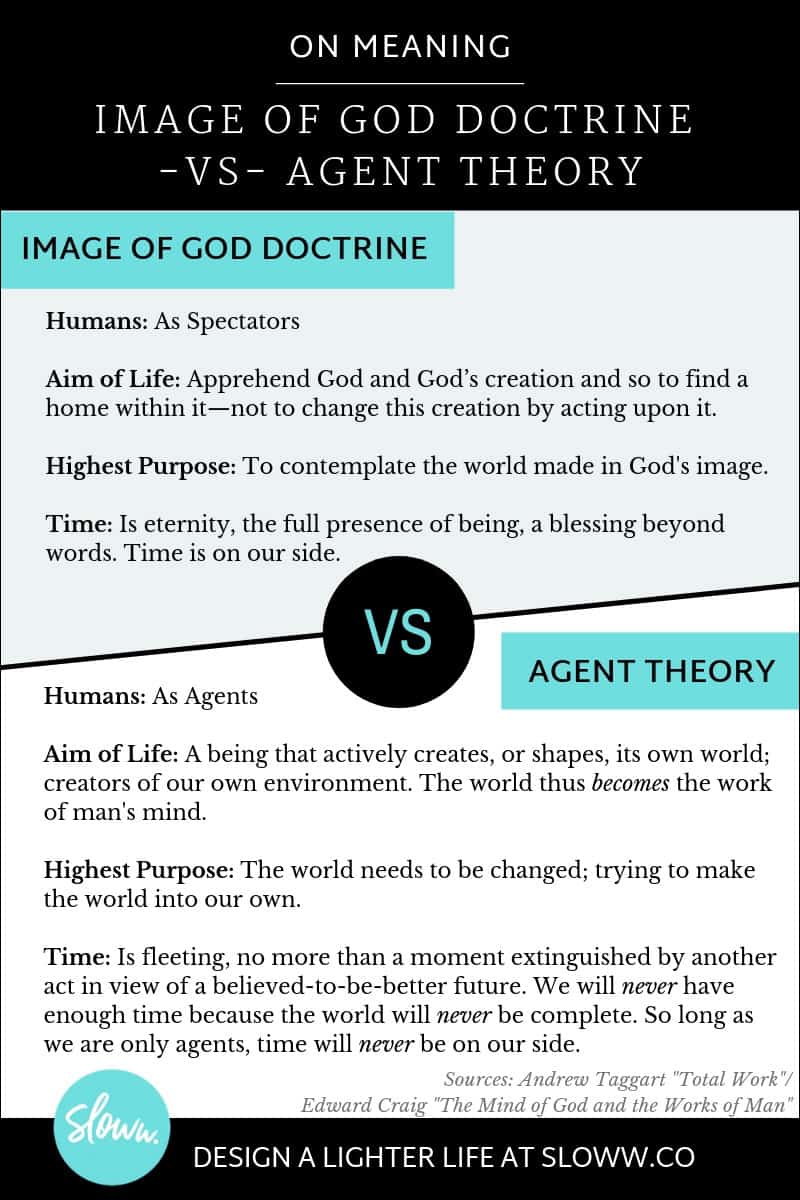

- “A world-changing historical transition that occurred in the eighteenth century: human beings left behind the idea that their highest purpose was to contemplate the world (called the ‘Image of God’ doctrine) and instead embraced the groundbreaking idea that the world needs to be changed (called the ‘Agent Theory’).”²

- “Our metaphysical stance toward the world thus shifted from one in which we are spectators—contemplating the world that was made in God’s image—to one in which we are agents, assiduously trying to make the world into our own. For the contemplator, time is eternity: the full presence of being, a blessing beyond words. For the agent, time is fleeting, no more than a moment extinguished by another act in view of a believed-to-be-better future. That’s because with agency comes an unacknowledged burden. We will never have enough time, because the world, ever beckoning us to take further actions, will never be complete. So long as we are only agents, time will never be on our side.”²

- “In Protestant’s hands, in time, insofar as God is calling each of us to have a calling, we will come to believe every able-bodied person, every able-minded person of a certain age, is expected to work. In the 19th century, this will mean the right to work. And, in the 20th century, this will be common sense as we assume that full-time gainful employment in the labor force is precisely what is expected of each human being…For the first time in human history…work itself becomes meaningful.”

We’ll come back to the “Image of God” Doctrine and “Agent Theory” in a minute. Ultimately, Taggart comes to this conclusion and explanation for how we got here:

- “What I see is that we’ve taken the bourgeois virtue of hard work, or productivity, and applied it to ourselves with ruthless persistence. But why? For three reasons. First, as progeny of the Bourgeois Revaluation, we, unlike aristocrats, have no wars to fight, honors to defend, courts to attend, leisurely hunts to go on, or liberal arts to pursue. Nor, unlike devout Christians of the medieval period, do we have inner spiritual struggles over which we can rend our souls. Rather, in the work society we have small betterments to make, tasks to complete, daily problems to solve, minor burdens to carry, modest marks to leave on the world before our time has come. Given this background, it makes some sense to throw ourselves into how we could improve on our bettering, especially our self-bettering.”³

The Meaning of Work & How to Evolve Beyond Total Work

“All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” — Blaise Pascal

I’ve lived the total work life. I suppose it was by my own unconscious doing by opting into a career of digital marketing. The marketing and advertising world is one thing, but the digital marketing world is the exact description of “what it looks and feels like to be a Total Worker” that was outlined above. It would take the better part of a decade for me to “wake up”—and it took a massive, life-changing existential crisis for me to do so. Needless to say, I’m wholeheartedly and wholemindedly interested in entertaining the possible ways to evolve beyond total work. I’ve experienced the attrition of my soul:

- “Our souls, so to speak, grow narrow and shallow over time in lieu of becoming vast and broad and deep. We become…pancake people.” — Andrew Taggart

“Pancake people”…that deserves an entire post on its own. For a later date.

Let’s start by going big—asking the big questions. This is something the majority of people actively avoid by choosing the escapism of busyness. Work has become the ultimate escapism from life. Taggart says:

- “The recovering lifehacker John Pavlus hints at this when he writes, ‘I think lifehacking is so seductive because it’s simply easier than asking some bigger, harder, more important questions about where your time and attention go.’ Those bigger, harder questions are philosophical in nature: Who am I? Why am I here? What is life ultimately about? Is there stillness beyond hustling? The work society, by promoting ceaseless busyness and ever greater productivity, prevents us from even asking ourselves these questions.”³

- “We are faced, therefore, with a stark choice: either we can waste our lives with total work or we can wake up to the kinds of lives that truly matter. And, if we wanted to wake up to the kinds of lives that truly matter, how would we go about doing so?”

We are going to ask those big questions: What is the meaning of work? Are humans born to work? Should life revolve around work? Should “Humans” simply be renamed “Workers”?

To do so, we need to start with meaning.

Let’s revisit the “Image of God” doctrine and “Agent Theory”—which of these do you believe?

There was a time as recently as a few years ago where I probably would have said I believe in “Agent Theory.” My work busyness completely blinded my life. But, that time has passed. Maybe I had to fail or be a figurative “loser” with workism, total work, and “Agent Theory” before I saw the light. Reminds me of this from Eckhart Tolle:

- “One thing we do know: Life will give you whatever experience is most helpful for the evolution of your consciousness.”

My existential crisis was the start of the consciousness evolution that I needed. I’m now a believer in something much larger, beyond ourselves. Call it God, Source, Universal Intelligence, or any other name you wish—I’m now a believer in the “Image of God” Doctrine.

What you believe drives your behavior, and your behavior determines who you become. This is why we must start with beliefs. You can derive your value of work based on which way you choose to find meaning in life.

Taggart believes:

- “Work is something you do, not something that happens to you…Meaning is not something you do but something that happens to you.”5

- “If meaning, understood as the ludic interaction of finitude and infinity, is precisely what transcends, here and now, the ken of our preoccupations and mundane tasks, enabling us to have a direct experience with what is greater than ourselves, then what is lost in a world of total work is the very possibility of our experiencing meaning. What is lost is seeking why we’re here.”¹

This resonates with me. It reminds me of this quote:

- “We are not human beings having a spiritual experience. We are spiritual beings having a human experience.” — Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

Challenging the concept of work isn’t new. Bertrand Russell, author of the essay In Praise of Idleness (1932), challenged the value and virtuousness of work during his day:

- “First of all: what is work? Work is of two kinds: first, altering the position of matter at or near the earth’s surface relatively to other such matter; second, telling other people to do so. The first kind is unpleasant and ill paid; the second is pleasant and highly paid.”

- “The fact is that moving matter about, while a certain amount of it is necessary to our existence, is emphatically not one of the ends of human life.”

- “I want to say, in all seriousness, that a great deal of harm is being done in the modern world by the belief in the virtuousness of work, and that the road to happiness and prosperity lies in an organized diminution of work.”

Here are a couple of the key insights from Russell:

- “There was formerly a capacity for light-heartedness and play which has been to some extent inhibited by the cult of efficiency. The modern man thinks that everything ought to be done for the sake of something else, and never for its own sake.”

- “Good nature is, of all moral qualities, the one that the world needs most, and good nature is the result of ease and security, not of a life of arduous struggle. Modern methods of production have given us the possibility of ease and security for all; we have chosen instead to have overwork for some and starvation for others. Hitherto we have continued to be as energetic as we were before there were machines. In this we have been foolish, but there is no reason to go on being foolish for ever.”

Then, sixteen years after Bertrand Russell’s In Praise of Idleness, the world was graced with Josef Pieper’s Leisure: The Basis of Culture. Let’s see if there’s anything else we can glean from Pieper’s words:

- “The opposite of acedia (despair of listlessness) is not the industrious spirit of the daily effort to make a living, but rather the cheerful affirmation by man of his own existence, of the world as a whole, and of God — of Love, that is, from which arises that special freshness of action, which would never be confused by anyone (who has) any experience with the narrow activity of the ‘workaholic.'”4

- “The ability to be ‘at leisure’ is one of the basic powers of the human soul. Like the gift of contemplative self-immersion in Being, and the ability to uplift one’s spirits in festivity, the power to be at leisure is the power to step beyond the working world and win contact with those superhuman, life-giving forces that can send us, renewed and alive again, into the busy world of work…”4

Maria Popova agrees with this sentiment about leisure:

- “And yet the most significant human achievements between Aristotle’s time and our own — our greatest art, the most enduring ideas of philosophy, the spark for every technological breakthrough — originated in leisure, in moments of unburdened contemplation, of absolute presence with the universe within one’s own mind and absolute attentiveness to life without.”4

John Maynard Keynes believes “how to occupy the leisure” is mankind’s ultimate challenge:

- “Thus for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem—how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.”

Here are some practical recommendations Taggart offers for all of us to consider to evolve beyond total work:

- “To begin with, we could critique the supreme value of work—questioning, for example, whether work shall be a calling for all of us. What if, I wonder, work needn’t be at the center of a life well-lived?”

- “Second, we could dis-identify from the work that we’re doing. Saying to ourselves, ‘Whoever I fundamentally, truly, ultimately am, I am not what I do for a living.’ Indeed, let that be our personal mantra: ‘I am not my work.'”

- “These things create space, which can be filled with vita contemplativa: the contemplative life. Love, joy, art, beauty, philosophy, wonderment, religion, spirituality, going beyond ego and puts us in touch with a greater abiding reality.”

- “I’ve come to believe that what must be discovered instead—and this is no easy thing—is the contemplative stillness that exists beneath any pace of life, whether fast, fluctuating, or slow, that sense of abiding peace that T.S. Eliot once so beautifully called ‘the still point of the turning world.’ How to find that abiding peace, that ground of Life, really is the question.”²

I’ll leave you to ponder Andrew Taggart’s vision of utopia:

- “My utopia is divided into two basic parts or domains: sustaining life (or infrastructure), and the good life (that for the sake of which we live). Sustaining life makes possible the good life, but is not the good life itself. Furthermore, the good life, in my utopia, is no more but no less than the expression of leisure…Leisure is a condition of the soul, a disposition of our being, a way of being in the world in which we are radically widely open to apprehending reality. More succinctly put, leisure is openness to what there is.”

Sustainaning Life:

- Human Work (Functions in accordance with natural rhythms: care, responsibility, fineness)

- Machine Work (Drudgery tasks, physical labor, mindless mind work tasks)

The Good Life:

- Vita Activa (Human Ecology, Civic Engagement

- Vita Contemplativa (Art, Philosophy, Science, Religion/Spirituality)

What do you believe?

For a more recent (but longer) video of Andrew Taggart, check out The Brief Story of How Work Took over the World and Made Us Who We Think We Are:

Sources:

- https://aeon.co/ideas/if-work-dominated-your-every-moment-would-life-be-worth-living

- https://qz.com/work/1272033/why-you-never-have-enough-time-a-history/

- https://qz.com/work/1186048/life-hacks-are-part-of-a-200-year-old-movement-to-destroy-your-humanity/

- https://www.brainpickings.org/2015/08/10/leisure-the-basis-of-culture-josef-pieper/

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/very-short-proof-showing-why-meaningful-work-andrew-taggart/

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/dont-read-work-andrew-taggart/

- http://fortune.com/2019/04/15/jack-ma-996-culture/