This is a book summary of Ultralearning: Master Hard Skills, Outsmart the Competition, and Accelerate Your Career by Scott Young (Amazon):

For an intro to Ultralearning and Scott Young, check out:

Quick Housekeeping:

- All content in quotation marks is from the author unless otherwise stated.

- All content is organized into my own themes (not the author’s chapters).

- Emphasis has been added in bold for readability/skimmability.

Book Summary Contents:

Become an Ultralearner: Ultralearning by Scott Young (Book Summary + Infographic)

About Ultralearning

“Learning, at its core, is a broadening of horizons, of seeing things that were previously invisible and of recognizing capabilities within yourself that you didn’t know existed. I see no higher justification for pursuing the intense and devoted efforts of the ultralearners I’ve described than this expansion of what is possible.”

What is Ultralearning?

“Ultralearning is a strategy for acquiring skills and knowledge that is both self-directed and intense … The core of the ultralearning strategy is intensity and a willingness to prioritize effectiveness.”

Ultralearning is:

- a strategy (a strategy is not the only solution to a given problem, but it may be a good one).

- self-directed and intense (it’s about how you make decisions about what to learn and why; because it is directed by learners themselves, it can fit into a wider variety of schedules and situations, targeting exactly what you need to learn without the waste).

- prioritizing deeply and effectively learning things.

- a potent skill for dealing with a changing world (the ability to learn hard things quickly is going to become increasingly valuable).

Who are Ultralearners?

“In writing this book, I wanted to bring together the common principles I observed in their unique projects and in my own. I wanted to strip away all the superficial differences and strange idiosyncrasies and see what learning advice remains.”

Ultralearners:

- pursue self-directed learning projects.

- tackle intense projects (even if it often comes at the sacrifice of credentials or conformity).

- usually work alone (often toiling for months and years without much more than a blog entry to announce their efforts).

- are motivated by a compelling vision of what they want to do, a deep curiosity, or even the challenge itself.

- blend the practical reasons for learning a skill with an inspiration that comes from something that excites them.

- have interests tending toward obsession.

- take unusual steps to maximize their effectiveness in learning and are aggressive about optimizing their strategies.

- fiercely debate the merits of esoteric concepts (such as interleaving practice, leech thresholds, or keyword mnemonics).

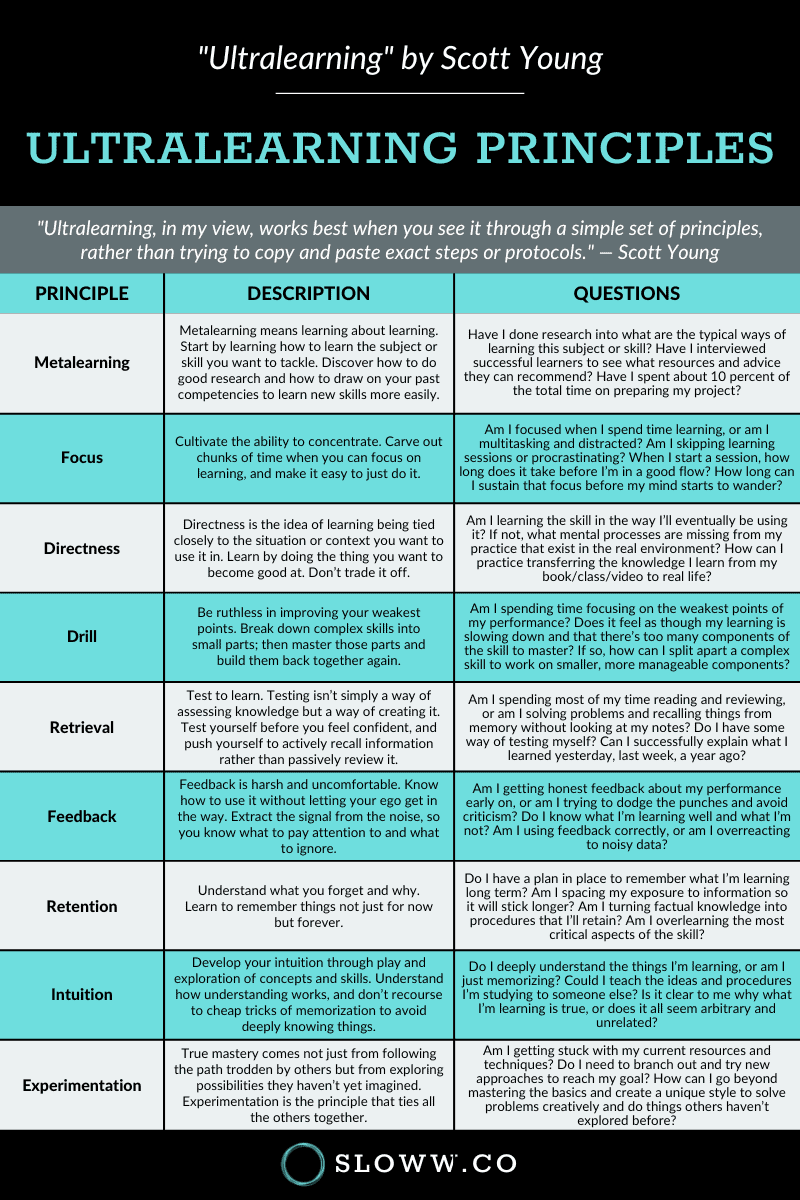

9 Ultralearning Principles

“Ultralearning, in my view, works best when you see it through a simple set of principles, rather than trying to copy and paste exact steps or protocols.”

Ultralearning Principle 1: Metalearning

“Metalearning means learning about learning … Start by learning how to learn the subject or skill you want to tackle. Discover how to do good research and how to draw on your past competencies to learn new skills more easily.”

- “Being able to see how a subject works, what kinds of skills and information must be mastered, and what methods are available to do so more effectively is at the heart of success of all ultralearning projects. Metalearning thus forms the map, showing you how to get to your destination without getting lost.”

- “Over the short term, you can do research to focus on improving your metalearning before and during a learning project. Ultralearning, owing to its intensity and self-directed nature, has the opportunity for a lot higher variance than normal schooling efforts do. A good ultralearning project, with excellent materials and an awareness of what needs to be learned, has the potential to be completed faster than formal schooling.”

- “Over the long term, the more ultralearning projects you do, the larger your set of general metalearning skills will be. You’ll know what your capacity is for learning, how you can best schedule your time and manage your motivation, and you’ll have well-tested strategies for dealing with common problems.”

- “The benefits of ultralearning aren’t always apparent from the first project because that first project occurs when you’re at your lowest level of metalearning ability. Each project you complete will give you new tools to tackle the next, starting a virtuous cycle.”

- “Instrumental learning projects are those you’re learning with the purpose of achieving a different, nonlearning result … Intrinsic projects are those that you’re pursuing for their own sake.”

Metalearning Questions:

· Have I done research into what are the typical ways of learning this subject or skill?

· Have I interviewed successful learners to see what resources and advice they can recommend?

· Have I spent about 10 percent of the total time on preparing my project?

Ultralearning Principle 2: Focus

“In the realm of great intellectual accomplishments an ability to focus quickly and deeply is nearly ubiquitous … Cultivate the ability to concentrate. Carve out chunks of time when you can focus on learning, and make it easy to just do it.”

- “The first problem that many people have is starting to focus. The most obvious way this manifests itself is when you procrastinate: instead of doing the thing you’re supposed to, you work on something else or slack off.”

- “The second problem people tend to encounter is an inability to sustain focus.”

- “A third, problem, subtler than the other two, has to do with the quality and direction of your attention.”

- “Researchers generally find that people retain more of what they learn when practice is broken into different studying periods than when it is crammed together. Similarly, the phenomenon of interleaving suggests that even within a solid block of focus, it can make sense to alternate between different aspects of the skill or knowledge to be remembered.”

Focus Questions:

· Am I focused when I spend time learning, or am I multitasking and distracted?

· Am I skipping learning sessions or procrastinating?

· When I start a session, how long does it take before I’m in a good flow?

· How long can I sustain that focus before my mind starts to wander?

· How sharp is my attention?

· Should it be more concentrated for intensity or more diffuse for creativity?

Ultralearning Principle 3: Directness

“Directness is the idea of learning being tied closely to the situation or context you want to use it in … Learn by doing the thing you want to become good at. Don’t trade it off for other tasks, just because those are more convenient or comfortable.”

- “Directness is closely related to the concept of ‘transfer-appropriate processing’ from psychological literature … Transfer has been called the ‘Holy Grail of education.’ It happens when you learn something in one context, say in a classroom, and are able to use it in another context, say in real life. Although this may sound technical, transfer really embodies something we expect of almost all learning efforts—that we’ll be able to use something we study in one situation and apply it to a new situation. Anything less than this is hard to describe as learning at all.”

- “Directness solves the problem of transfer in two ways. The first and most obvious is that if you learn with a direct connection to the area in which you eventually want to apply the skill, the need for far transfer is significantly reduced … Second, I believe that directness may help with transfer to new situations, beyond its more obvious role in preventing the need for far transfer. Many real-life situations share many subtle details with other real-life situations that they never share with the abstract environment of the classroom or textbook.”

- “When we learn new things, we should always strive to tie them directly to the contexts we want to use them in. Building knowledge outward from the kernel of a real situation is much better than the traditional strategy of learning something and hoping that we’ll be able to shift it into a real context at some undetermined future time.”

- “Although the findings of the research on transfer are fairly bleak, there is a glimmer of hope, which is that gaining a deeper knowledge of a subject will make it more flexible for future transfer. Whereas the structures of our knowledge start out brittle, welded to the environments and contexts we learn them in, with more work and time they can become flexible and can be applied more broadly.”

Directness Questions:

· Am I learning the skill in the way I’ll eventually be using it?

· If not, what mental processes are missing from my practice that exist in the real environment?

· How can I practice transferring the knowledge I learn from my book/class/video to real life?

Ultralearning Principle 4: Drill

“A drill takes the direct practice and cuts it apart, so that you are practicing only an isolated component … Be ruthless in improving your weakest points. Break down complex skills into small parts; then master those parts and build them back together again.”

- “In chemistry, there’s a useful concept known as the ‘rate-determining step.’ This occurs when a reaction takes place over multiple steps, with the products of one reaction becoming the reagents for another. The rate-determining step is the slowest part of this chain of reactions, forming a bottleneck that ultimately defines the amount of time needed for the entire reaction to occur. Learning, I’d like to argue, often works similarly, with certain aspects of the learning problem forming a bottleneck that controls the speed at which you can become more proficient overall.”

- “This is the strategy behind doing drills. By identifying a rate-determining step in your learning reaction, you can isolate it and work on it specifically. Since it governs the overall competence you have with that skill, by improving at it you will improve faster than if you try to practice every aspect of the skill at once.”

- “Ultralearners frequently employ what I’ll call the ‘Direct-Then-Drill Approach.’ The first step is to try to practice the skill directly. This means figuring out where and how the skill will be used and then trying to match that situation as close as is feasible when practicing … The next step is to analyze the direct skill and try to isolate components that are either rate-determining steps in your performance or subskills you find difficult to improve because there are too many other things going on for you to focus on them. From here you can develop drills and practice those components separately until you get better at them. The final step is to go back to direct practice and integrate what you’ve learned.”

Drill Questions:

· Am I spending time focusing on the weakest points of my performance?

· What is the rate-limiting step that is holding me back?

· Does it feel as though my learning is slowing down and that there’s too many components of the skill to master?

· If so, how can I split apart a complex skill to work on smaller, more manageable components of it?

Ultralearning Principle 5: Retrieval

“Test to learn. Testing isn’t simply a way of assessing knowledge but a way of creating it. Test yourself before you feel confident, and push yourself to actively recall information rather than passively review it.”

- “What makes practicing retrieval so much better than review? One answer comes from the psychologist R. A. Bjork’s concept of ‘desirable difficulty.‘ More difficult retrieval leads to better learning, provided the act of retrieval is itself successful.”

- “Difficulty, far from being an obstacle to making retrieval work, may be part of the reason it does so.”

- “The idea of desirable difficulties in retrieval makes a potent case for the ultralearning strategy. Low-intensity learning strategies typically involve either less or easier retrieval. Pushing difficulty higher and opting for testing oneself well before you are ‘ready’ is more efficient.”

Retrieval Questions:

· Am I spending most of my time reading and reviewing, or am I solving problems and recalling things from memory without looking at my notes?

· Do I have some way of testing myself, or do I just assume I’ll remember?

· Can I successfully explain what I learned yesterday, last week, a year ago?

· How do I know if I can?

Ultralearning Principle 6: Feedback

“Feedback is harsh and uncomfortable. Know how to use it without letting your ego get in the way. Extract the signal from the noise, so you know what to pay attention to and what to ignore.”

- “What often separated the ultralearning strategy from more conventional approaches was the immediacy, accuracy, and intensity of the feedback being provided.”

- “Feedback features prominently in the research on deliberate practice, a scientific theory of the acquisition of expertise initiated by K. Anders Ericsson and other psychologists. In his studies, Ericsson has found that the ability to gain immediate feedback on one’s performance is an essential ingredient in reaching expert levels of performance.”

- “Though short-term feedback can be stressful, once you get into the habit of receiving it, it becomes easier to process without overreacting emotionally. Ultralearners use this to their advantage, exposing themselves to massive amounts of feedback so that the noise can be stripped away from the signal.”

Feedback Questions:

· Am I getting honest feedback about my performance early on, or am I trying to dodge the punches and avoid criticism?

· Do I know what I’m learning well and what I’m not?

· Am I using feedback correctly, or am I overreacting to noisy data?

Ultralearning Principle 7: Retention

“Understand what you forget and why. Learn to remember things not just for now but forever.”

- “Psychologists have identified at least three dominant theories to help explain why our brains forget much of what we initially learn: decay, interference, and forgotten cues.”

- “The first theory of forgetting is that memories simply decay with time.”

- “Interference suggests a different idea: that our memories, unlike the files of a computer, overlap one another in how they are stored in the brain. In this way, memories that are similar but distinct can compete with one another.”

- “The third theory of forgetting says that many memories we have aren’t actually forgotten but simply inaccessible. The idea here is that in order to say that one has remembered something, it needs to be retrieved from memory. Since we aren’t constantly experiencing the entirety of our long-term memories simultaneously, this means there must be some process for dredging up the information, given an appropriate cue. What may happen in this case is that one of the links in the chain of retrieving the information has been severed (perhaps by decay or interference) and therefore the entire memory has become inaccessible. However, if that cue were restored, or if an alternative path to the information could be found, we would remember much more than is currently accessible to us.”

Retention Questions:

· Do I have a plan in place to remember what I’m learning long term?

· Am I spacing my exposure to information so it will stick longer?

· Am I turning factual knowledge into procedures that I’ll retain?

· Am I overlearning the most critical aspects of the skill?

Ultralearning Principle 8: Intuition

“Develop your intuition through play and exploration of concepts and skills. Understand how understanding works, and don’t recourse to cheap tricks of memorization to avoid deeply knowing things.”

- “Only by developing enough experience with problem solving can you build up a deep mental model of how other problems work. Intuition sounds magical, but the reality may be more banal—the product of a large volume of organized experience dealing with the problem.”

Intuition Questions:

· Do I deeply understand the things I’m learning, or am I just memorizing?

· Could I teach the ideas and procedures I’m studying to someone else?

· Is it clear to me why what I’m learning is true, or does it all seem arbitrary and unrelated?

Ultralearning Principle 9: Experimentation

“All of these principles are only starting points. True mastery comes not just from following the path trodden by others but from exploring possibilities they haven’t yet imagined … Experimentation is the principle that ties all the others together. Not only does it make you try new things and think hard about how to solve specific learning challenges, it also encourages you to be ruthless in discarding methods that don’t work. Careful experimentation not only brings out your best potential, it also eliminates bad habits and superstitions by putting them to the test of real-world results.”

- “As your skill develops, it’s often no longer enough to simply follow the examples of others; you need to experiment and find your own path. Part of the reason for this is that the early part of learning a skill tends to be the best trodden and supported, as everyone begins at the same place. As your skills develop, however, not only are there fewer people who can teach you and fewer students you could have as peers (thus lowering the total market for books, classes, and instructors), but you also start to diverge from those you’re learning from.”

- “A second reason for the value of experimentation as you approach mastery is that abilities are more likely to stagnate after you’ve mastered the basics. Learning in the early phases of a skill is an act of accumulation. You acquire new facts, knowledge, and skills to handle problems you didn’t know how to solve before. Getting better, however, increasingly becomes an act of unlearning; not only must you learn to solve problems you couldn’t before, you must unlearn stale and ineffective approaches for solving those problems.”

- “A final reason for the increasing importance of experimentation as you approach mastery is that many skills reward not only proficiency but originality.”

- “I see the experimental mindset as an extension of the growth mindset: whereas the growth mindset encourages you to see opportunities and potential for improvement, experimentation enacts a plan to reach those improvements. The experimental mindset doesn’t just assume that growth is possible but creates an active strategy for exploring all the possible ways to reach it.”

- “Learning is a process of experimenting in two ways. First, the act of learning itself is a kind of trial and error. Practicing directly, getting feedback, and trying to summon up the right answers to problems are all ways of adjusting the knowledge and skills you have in your head to the real world. Second, the act of experimenting also lies in the process of trying out your learning methods. Try out different approaches, and use the ones that work best for you.”

Experimentation Questions:

· Am I getting stuck with my current resources and techniques?

· Do I need to branch out and try new approaches to reach my goal?

· How can I go beyond mastering the basics and create a unique style to solve problems creatively and do things others haven’t explored before?

You May Also Enjoy:

- See all book summaries

- Range by David Epstein | Book Summary

- A Synthesizing Mind by Howard Gardner | Book Summary

- How to Read a Book by Mortimer Adler | Book Summary | 🔒 How to Apply It

- How to Take Smart Notes by Sönke Ahrens | Book Summary 1, 2 | 🔒 How to Apply It