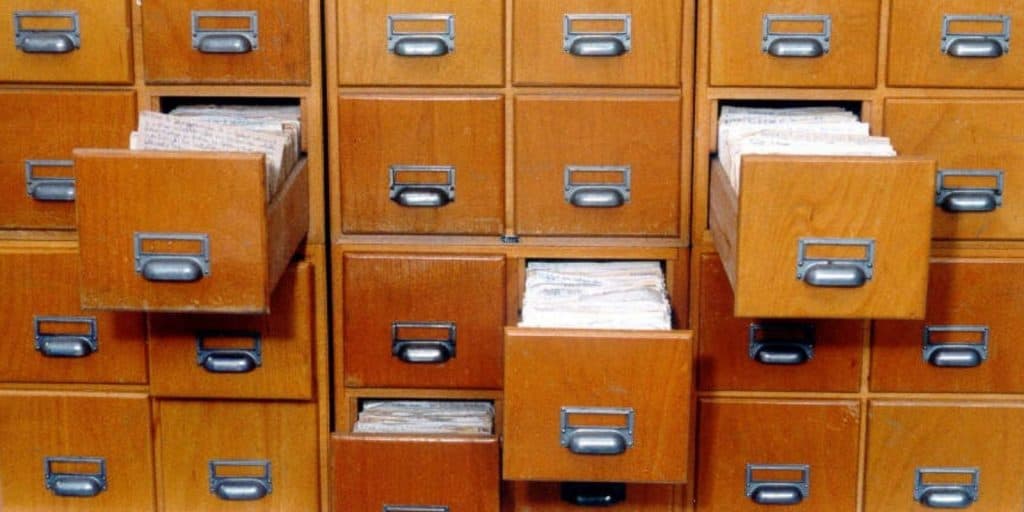

The zettelkasten (German for “slip box”) is a method of note-taking and personal knowledge management used in research and study.1

I was introduced to the concept through the book “How to Take Smart Notes” by Sönke Ahrens (Book Summary | 🔒Premium Summary | Amazon):

“The particular technique presented in this book enabled Niklas Luhmann to become one of the most productive and innovative social theorists of the last century. There are increasing numbers of academics and nonfiction writers taking notice.” — Sönke Ahrens

In the book, Ahrens highlights the zettelkasten system of Niklas Luhmann. While Luhmann wasn’t the first to use the system, he’s certainly one of the most prolific. In his lifetime, Luhmann made ~90,000 handwritten notes (now being digitized!) over the course of ~40 years—which he used to write ~600 publications including ~60 books! It’s mind boggling on a macro scale. But, when you consider it on a micro scale, it averages out to just 6 notes per day. Much more doable.

Quick Housekeeping:

- All quotes are from Sönke Ahrens (“How to Take Smart Notes”) unless otherwise specified.

- I’ve organized content into my own themes.

- I’ve added emphasis in bold throughout for readability/skimmability.

Post Contents: Click a link here to jump to a section below

Zettelkasten 101: An Intro to the Smart Note-Taking System of Niklas Luhmann

Who was Niklas Luhmann?

“One cannot think without writing.” — Niklas Luhmann

I could write up a full bio here, but perhaps the best way to introduce yourself to Luhmann is to experience him for yourself. These two videos will not only give you a visual intro to Luhmann, they will also give you an overview of his zettelkasten system (use English subtitles):

Here’s another video in German (although the English translation isn’t as good as the previous video, it will still give you the gist):

The Strategy behind the Niklas Luhmann Zettelkasten System

Luhmann referred to his zettelkasten as his “second memory.”2

In his own words:

- “Underlying the filing technique is the experience that without writing, there is no thinking.”2

- “I always read with an eye towards possible connections in the slip-box.”

- “I, of course, do not think everything by myself. It happens mainly within the slip-box.”

- (The zettelkasten is a) “combination of disorder and order, of clustering and unpredictable combinations emerging from ad hoc selection.”2

- (What matters is) “what could be utilized in which way for the cards that had already been written. Hence, when reading, I always have the question in mind of how the books can be integrated into the filing system.”2

- “When I am stuck for one moment, I leave it and do something else … I always work on different manuscripts at the same time. With this method, to work on different things simultaneously, I never encounter any mental blockages.”

- “If I want something, it’s more time. The only thing that really is a nuisance is the lack of time.”

The Tactics behind the Niklas Luhmann Zettelkasten System

The following quotes all come from “How to Take Smart Notes” by Sönke Ahrens:

Reading:

“One has to read extremely selectively and extract widespread and connected references. One has to be able to follow recurrences.” — Niklas Luhmann

- “Luhmann almost never read a text twice (Hagen 1997) and was still regarded as an impressive conversation partner who seemed to have all information ready to hand.”

- “Whenever (Niklas Luhmann) encountered something remarkable or had a thought about what he read, he made a note.”

Note-taking:

“Probably the best method is to take notes – not excerpts, but condensed reformulated accounts of a text. Rewriting what was already written almost automatically trains one to shift the attention towards frames, patterns and categories in the observations, or the conditions/assumptions, which enable certain, but not other descriptions.” — Niklas Luhmann

- “Instead of adding notes to existing categories or the respective texts, he wrote them all on small pieces of paper, put a number in the corner and collected them in one place: the slip-box.”

- “He did not just copy ideas or quotes from the texts he read, but made a transition from one context to another. It was very much like a translation where you use different words that fit a different context, but strive to keep the original meaning as truthfully as possible.”

Connecting Notes:

“Every note is just an element in the network of references and back references in the system, from which it gains its quality.” — Niklas Luhmann

- “Luhmann, certainly being on the outer spectrum of expertise, contented himself with pretty short notes and was still able to turn them into valuable slip-box notes without distorting the meaning of the original texts. It is mainly a matter of having an extensive latticework of mental models or theories in our heads that enable us to identify and describe the main ideas quickly.”

- “By adding these links between notes, Luhmann was able to add the same note to different contexts. While other systems start with a preconceived order of topics, Luhmann developed topics bottom up, then added another note to his slip-box, on which he would sort a topic by sorting the links of the relevant other notes.”

- “He soon developed new categories of these notes. He realised that one idea, one note was only as valuable as its context, which was not necessarily the context it was taken from. So he started to think about how one idea could relate and contribute to different contexts. Just amassing notes in one place would not lead to anything other than a mass of notes. But he collected his notes in his slip-box in such a way that the collection became much more than the sum of its parts. His slip-box became his dialogue partner, main idea generator and productivity engine. It helped him to structure and develop his thoughts. And it was fun to work with – because it worked.”

Numbering Notes:

“The trick is that he did not organise his notes by topic, but in the rather abstract way of giving them fixed numbers. The numbers bore no meaning and were only there to identify each note permanently.”

- “If a new note was relevant or directly referred to an already existing note, such as a comment, correction or addition, he added it directly behind the previous note. If the existing note had the number 22, the new note would become note number 23. If 23 already existed, he named the new note 22a. By alternating numbers and letters, with some slashes and commas in between, he was able to branch out into as many strings of thought as he liked. For example, a note about causality and systems theory carried the number 21/3d7a7 following a note with the number 21/3d7a6.”

- “Luhmann would add the number of one or two (rarely more) notes next to a keyword in the index (Schmidt 2013, 171). The reason he was so economical with notes per keyword and why we too should be very selective lies in the way the slip-box is used. Because it should not be used as an archive, where we just take out what we put in, but as a system to think with, the references between the notes are much more important than the references from the index to a single note. Focusing exclusively on the index would basically mean that we always know upfront what we are looking for – we would have to have a fully developed plan in our heads. But liberating our brains from the task of organizing the notes is the main reason we use the slip-box in the first place.”

Four Types of Cross-References:

Luhmann used four basic types of cross-references in his file-box:

1. “The first type of links are those on notes that are giving you the overview of a topic. These are notes directly referred to from the index and usually used as an entry point into a topic that has already developed to such a degree that an overview is needed or at least becomes helpful. On a note like this, you can collect links to other relevant notes to this topic or question, preferably with a short indication of what to find on these notes (one or two words or a short sentence is sufficient). This kind of note helps to structure thoughts and can be seen as an in-between step towards the development of a manuscript. Above all, they help orientate oneself within the slip-box. You will know when you need to write one. Luhmann collected up to 25 links to other notes on these kind of entry notes. They don’t have to be written in one go as links can be added over time, which again shows how topics can grow organically. What we think is relevant for a topic and what is not depends on our current understanding and should be taken quite seriously: It defines an idea as much as the facts it is based on. What we regard as being relevant for a topic and how we structure it will change over time. This change might lead to another note with a different, more adequate topic structure, which then can be seen as a comment on the previous note.”

2. “A similar though less crucial kind of link collection is on those notes that give an overview of a local, physical cluster of the slip-box. This is only necessary if you work with pen and paper like Luhmann. While the first type of note gives an overview of a topic, regardless of where the notes are located within the slip-box, this type of note is a pragmatic way of keeping track of all the different topics discussed on the notes that are physically close together. As Luhmann put notes between notes to internally branch out subtopics and sub-subtopics, original lines of thoughts were often interrupted by hundreds of different notes. This second type of note keeps track of the original lines of thought. Obviously, we don’t need to worry about this if we work with the digital version.”

3. “Equally less relevant for the digital version are those links that indicate the note to which the current note is a follow-up and those links that indicate the note that follows on the current note. Again, this is only relevant to see which notes follow each other, even if they don’t physically stand behind each other anymore. The digital Zettelkasten automatically adds these kinds of backlinks and presents you the relevant notes in a note sequence.”

4. “The most common form of reference is plain note-to-note links. They have no function other than indicating a relevant connection between two individual notes. By linking two related notes regardless of where they are within the slip-box or within different contexts, surprising new lines of thought can be established. These note-to-note links are like the ‘weak links’ of social relationships we have with acquaintances: even though they are usually not the ones we turn to first, they often can offer new and different perspectives.”

Have you tried a Zettelkasten system? Do you use a physical or digital zettelkasten? Let me know in the comments.

I’m currently migrating my “second memory” from Evernote to Obsidian (and loving Obsidian so far).

You May Also Enjoy:

- See all book summaries

- Next-Level Note-Taking: “How to Take Smart Notes” by Sönke Ahrens (Book Summary) + 🔒 Premium Summary

Sources & Footnotes:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zettelkasten

- https://sociologica.unibo.it/article/view/8350/8272